In downtown Minneapolis, two light rail trains pass on 5th St., a major east-west thoroughfare with dedicated lanes for light rail. Photo: L. Henry.

♦

Last month, the 13th National Light Rail Conference, co-sponsored by the American Public Transportation Association (APTA) and U.S. Transportation Research Board (TRB), was held in Minneapolis, whose initial light rail transit (LRT) starter line has been operating since 2004 (see «Minneapolis-St. Paul (Twin Cities) Public Transport»). Attending the conference were two contributors to Austin Rail Now, Dave Dobbs and Lyndon Henry.

Minneapolis’s LRT system has been a spectacular success — particularly by exceeding ridership projections and providing more efficient and cost-effective transit service through lowering the average operating and maintenance (O&M) cost of urban transit per passenger-mile. Add to that the significant improvement of urban mobility and livability. This has convinced local policymakers and planners that further investment and expansion of the system are justified, leading to the opening of a second route, crossing the Mississippi River and connecting the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, in 2014. Additional routes are now in development, and the Northstar Line, a regional passenger rail (commuter) line serving northwest suburbs and exurban communities, was also launched in 2009. See: «Minneapolis Area: Northstar Regional Rail Links Northwest Communities With Central City».

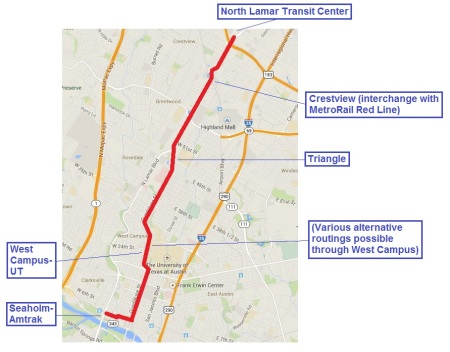

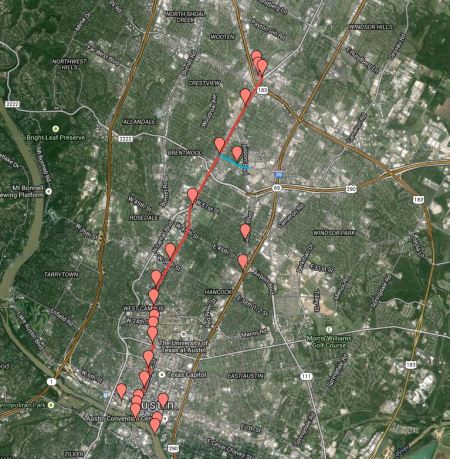

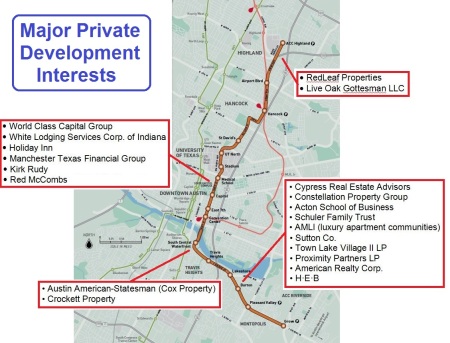

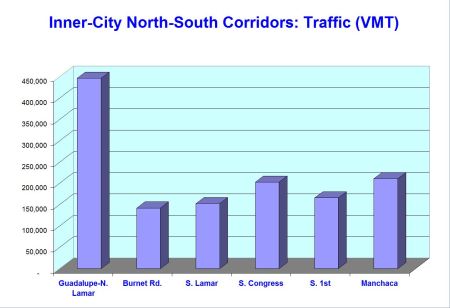

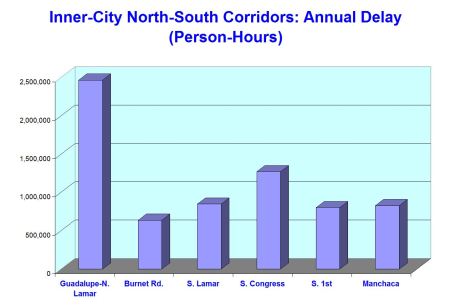

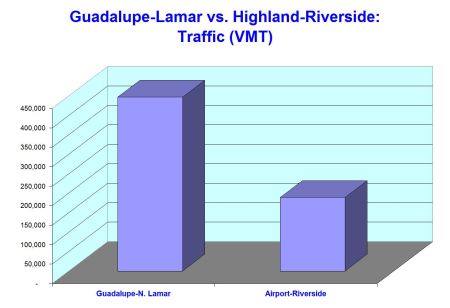

Overall, the Minneapolis LRT system appears to be a highly appropriate model for other cities — and especially Austin, where community support has been growing for an LRT starter line project in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor (Guadalupe St.-North Lamar Blvd.). (See «Plan for galvanizing Austin’s public transport development: Light rail starter line in Guadalupe-Lamar».) As with Minneapolis’s original starter line, Austin’s Guadalupe-Lamar LRT line could serve as the trunk or spine for additional lines branching out into other segments of the urban area.

This article/photo-essay presents a brief summary description of the Minneapolis LRT system and focuses especially on particular features that highlight why LRT is such an exceptionally appropriate and desirable public transport mode for a city like Austin.

Overview

So far, the Twin Cities LRT system extends approximately 23 miles, mainly south and east of central Minneapolis, as illustrated in the map below.

Map of Minneapolis Metro Transit rail transit system shows Blue and Green LRT Lines plus Northstar regional rail line (grey) to the northwest. Map adapted by ARN from Metro Transit map. (Click to enlarge.)

► Blue Line — Originally dubbed the Hiawatha Line because much of its alignment uses a former railroad right-of-way (ROW) paralleling the city’s Hiawatha Avenue, the initial route (opened 2004) is now designated the Blue Line. Extended slightly, it now stretches about 12 miles south from the city’s downtown to the airport and terminates at the Mall of America. In the CBD, generally from the Downtown East station west, the Blue Line runs in dedicated lanes within 5th Street — in effect, a quasi-transit-mall configuration with some access allocated to motor vehicles (see photo at top of post).

Outside the city’s core area, much of the Blue Line alignment, running on former freight railroad right-of-way, parallels Hiawatha Avenue, seen on the far left in this view. Photo: L. Henry. (Click to enlarge.)

Blue Line train at Cedar-Riverside station, closer in to the CBD, where the former railroad ROW is quite narrow. This is similar to the narrow railroad ROW of Austin’s MetroRail (Red Line), which ARN and other groups have advocated to be converted to LRT (from its current status as a diesel-propulsion light railway). LRT’s electric propulsion enables faster, smoother train operation that is cheaper, cleaner, and friendlier to urban livability. (Photo: L. Henry.)

► Green Line — Also called the Central Line, this 11-mile route (opened 2014) crosses the Mississippi River to link the downtowns of Minneapolis and St. Paul. It also re-establishes what was once the Twin Cities’ formerly busiest streetcar route, part of the region’s vast, efficient electric rail system destroyed in the 1950s amidst the widespread national Transit Devastation, when public policy eliminated urban and interurban electric railways in a disastrous effort to encourage (and coerce) the American population to rely exclusively on personal automobiles and other rubber-tired transport (buses) rather than urban and interurban electric rail for mobility.

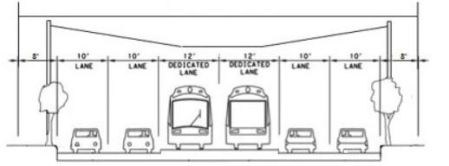

In contrast to the Blue Line, the Green Line is routed almost entirely via dedicated lanes or reservations within major arterials and other thoroughfares, with a particularly long stretch along University Avenue west of the Mississippi and toward St. Paul. In the Minneapolis CBD, the Green Line shares dedicated tracks on 5th St. with the Blue Line. Also of note is the use of the iconic Washington Avenue bridge (retrofitted to accommodate LRT) to cross the Mississippi River, as discussed further below.

► Joint use of 5th St. trunk line — As mentioned above, both the Blue and Green Lines share tracks of the original 5th St. trunk route in downtown Minneapolis. A section of this alignment is illustrated in the photo at the top of this post. The following photo shows one of the stations in this alignment.

Passengers awaiting arrival of Green Line train at downtown Warehouse District/Hennepin Avenue station in 5th St. alignment. Photo: L. Henry.

► Self-service fare system — As with most new LRT systems, the Minneapolis operation uses self-service fare collection. Passengers purchase tickets at ticket vending machines (TVMs). Roving inspectors then spot-check passengers’ tickets aboard trains. (Austin’s MetroRail also uses the self-service system.)

► Rail access/interconnections among major activity centers — The Twin Cities LRT system is outstanding in accessing and interconnecting some of the urban area’s most significant activity centers. These include, for example:

• Downtown Minneapolis

• Downtown St. Paul

• Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport

• Twin Cities Amtrak station (Union Depot, St. Paul)

• University of Minnesota (St. Paul)

• Minnesota state capitol (St. Paul)

• VA Medical Center

• Major shopping malls (Mall of America and University Ave. West/Hamline Ave.)

• Target Field sports center

Airport access

LRT can provide a cost-effective way to implement rail access to a city’s major local airport. However, typically the heaviest airport ridership tends to come from employees rather than passengers, so to be cost-effective the LRT route must also serve other significant sources of ridership close by (exemplified by LRT routes to airports in Baltimore, St. Louis, Portland, Phoenix, Seattle, Dallas, and Salt Lake City).

Minneapolis’s Blue Line LRT strongly fulfills this requirement, since its airport stations are situated in the middle of good traffic generators on both sides (between the CBD on the north end and the Mall of America on the south end, with other activity centers and residential areas also in between). From visual observation, it’s clear that lots of passengers and airline crews utilize the convenience of the LRT connection.

Lots of visible baggage on Blue Line train gives an indication that LRT service to Minneapolis’s airport is well-used by air passengers. Photo: L. Henry.

Traveler with baggage boards Blue Line train at downtown station. With level boarding (station platform level with car floor), carrying on luggage is easy. Photo: L. Henry.

Shopping mall access

Access to shopping malls is a major advantage for any rail transit line, and a huge convenience for the public (especially out-of-town visitors). The Minneapolis LRT system provides access to malls in both Bloomington (south of Minneapolis) and St. Paul.

Blue Line train leaves the Mall of America station located in the parking garage of this giant mall, which hosts the most mall visitors in the world and is a popular tourist destination. Photo: Ymtram.mashke.org.

Green Line’s Hamline station accesses major mall on University Ave. at West/Hamline Ave., with two “big box” stores (Walmart and Target). Photo: L. Henry.

Bridge retrofitted for LRT

To cross the Mississippi River, the Green Line uses the iconic Washington Avenue bridge, rather than a specially built bridge. According to the Minneapolis Metro Council, retrofitting the bridge rendered “cost savings to the project estimated at $80 million to $100 million and a minimum of two years in project schedule in comparison to a full bridge replacement.” The bridge was retrofitted “for an estimated $21 million, $2 million under budget….”

In Austin, ARN and other groups have advocated retrofitting either the Congress Avenue or South First (Drake) bridge to cross Lady Bird Lake (Colorado River) and link South Austin to the rest of the city on the north side of the river. We suggest this would be far more financially accessible and cost-effective than the expense of a totally new, specially constructed bridge.

Green Line train crosses over Mississippi River on newly retrofitted Washington Ave. bridge. Photo: Streets.mn.

Solution to complicated intersections

Somewhat like Austin’s MetroRail alignment along Airport Blvd., the Minneapolis Blue Line along Hiawatha Avenue encounters design challenges at intersections, especially where these approach at an angle. How these problems have been dealt with may suggest some traffic solutions in Austin with respect to a potential intersection of road traffic with a proposed Guadalupe-Lamar LRT at Airport/North Lamar.

In this Google Earth view, Hiawatha Ave., with the LRT line paralleling it on its western edge, runs diagonally north-south through the center of the photo. The 38th St. LRT station can also be seen, while E. 38th St. crosses both LRT line and Hiawatha Ave. east-west, in the bottom third of the graphic. Note that Hiawatha and the LRT line intersect E. 38th St. at about a 60-degree angle, somewhat similarly to Airport Blvd and N. Lamar and the MetroRail Red Line in Austin. Photo: ARN, from Google Earth.

From a surface view, this shows the intersection protected with crossing gates. Photo: ARN, from Google Street View.

Easy transport of bicycles

With typically spacious vehicles, LRT has the advantage of accommodating onboard bicycles, in contrast with the constrained interior space of buses, which usually require cyclists to place their bikes on an outside rack (if one is available). These views show how bikes are accommodated aboard Twin Cities LRT trains.

Easy accessibility for mobility-challenged

Level boarding, spacious interiors, and smooth ride qualities mean that LRT cars are exceptional in their ability to accommodate disabled, wheelchair-using, and other mobility challenged passengers. This also means that long delays in boarding wheelchairs, typical of buses, are eliminated, thus speeding transit service for all.

Passenger in wheelchair easily maneuvers chair into accessible space aboard car. In contrast to buses — no tiedowns, no operator assistance needed, no passengers ousted from their seats! Photo: L. Henry.

Summing up

Certainly, a reasonable case can be made for considering Minneapolis (along with Portland, Salt Lake City, Phoenix, and several other cities) as a particularly appropriate model for designing an LRT system for Austin, starting in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. As this discussion/photo-essay has attempted to suggest, smart, cost-effective design can be combined with significant public transit conveniences and advantages to galvanize public support, attract significant ridership. improve mobility and urban livability, and reduce the cost burden of urban travel. ■