♦

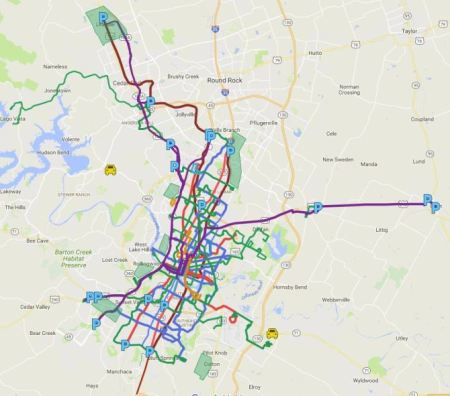

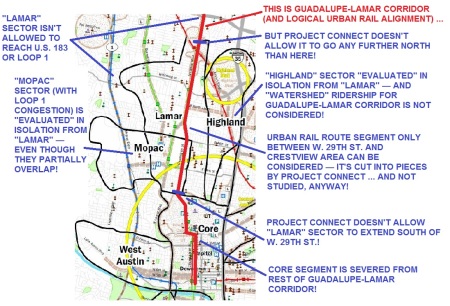

In a post this past February 28th, we reported on a surprising development coming from Capital Metro’s Project Connect planning process – the “conceptual” proposal of a 21-mile predominantly linear north-south light rail transit (LRT) corridor, running from Tech Ridge in North Austin, through the central heart of the city, to Slaughter Lane, near the Southpark Meadows area, in South Austin. The proposal particularly extolled the merits of a 12-mile-long segment, through the Lamar-Guadalupe corridor, from Tech Ridge to downtown.

After over four decades of indecision, missteps, and delay, it seemed like the transit agency (and city leadership) might, amazingly, have turned a corner. Could this actually mean that, at long last, Capital Metro and Austin’s top leadership were prepared to move ahead with a plausible, workable light rail plan – implementing a long-awaited leap forward in urban mobility – for the city’s most important central corridor?

Unfortunately, no. Slightly over a month later, Capital Metro reversed itself, withdrew the LRT proposal, and reverted to the familiar decades-long pattern of indecision, confusion, dithering, and delay that has gripped Austin like a curse.

Instead of an actual, specific project for a new light rail system, with a starter line from Tech Ridge to Republic Square downtown, the proposal had dissolved into the clouds, becoming just another line on a map of “perhaps something, some day”. To explain the retreat, planning was now described as “mode agnostic” – in other words, reverting back to a kind of official daydreaming, without any modes (the things that people would actually ride) identified to define a real-world project.

Almost exactly a month later, Capital Metro’s board made another fateful decision. Whereas mode-specific recommendations from the Project Connect study were scheduled for June, the board delayed that back to late in the fall (or perhaps winter) – far too late to put any kind of actual, mode-specific project (such as the previous LRT proposal) on the November ballot for possible voter approval of bond funding. (At best, this would now delay voter approval of any hypothetical project until the 2020 election cycle.)

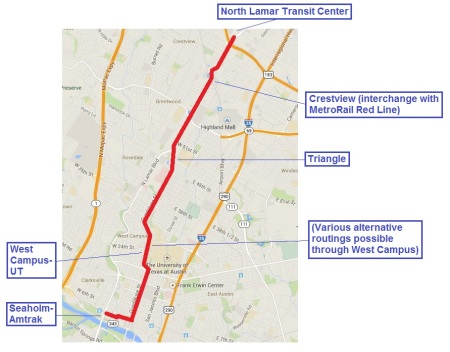

A third blow against LRT in the Lamar-Guadalupe corridor was struck on May 8th, when the Capital Area Mobility Planning Organization (CAMPO) approved a Capital Metro-sponsored plan (originally submitted Jan. 19th) to overhaul the N. Lamar Blvd.-Airport Blvd.-MetroRail intersection (adjacent to the Crestview MetroRail station) with a design – exclusively focused on accommodating and facilitating motor vehicle traffic, rather than public transport – that would impose enormous obstacles to LRT on North Lamar. Currently, community activists and urban rail advocates are endeavoring to prompt a redesign of this project.

For decade after decade, the Austin community has agonized, writhed, and wailed over its steadily mounting mobility crisis. Hundreds of miles of lanes and roads have been built and rebuilt, and even more vigorous roadbuilding is currently underway. Yet the mobility crisis continues to worsen – for many motorists, driving around the urban area increasingly feels like trying to swim through solidifying mud. Or, alternatively, slogging through a battlefield ….

Repeatedly, the need for light rail has been affirmed. (See «Long saga of Guadalupe-Lamar light rail planning told in maps».) As we pointed out in a March 2015 post, “For two and a half decades, local officials and planners have explained why urban rail — affordable light rail transit (LRT), in Austin’s case — has been an absolutely essential component of the metro area’s mobility future.” («Austin’s urban transport planning seems struck by catastrophic case of amnesia and confusion».)

Capital Metro designated LRT in the Lamar-Guadalupe corridor as the region’s Locally Preferred Alternative in 1989. In 2000, Capital Metro hastily placed LRT on the ballot – but, in a poorly organized election campaign, it was defeated in the overall service area by a tiny margin (although it was approved by Austin voters). In 2014, another LRT plan was presented to Austin voters under the slogan “Rail or Fail” – but, proposed for the ridiculously weak Highland-Riverside corridor, the plan was resoundingly rejected. (See «Austin: Flawed urban rail plan defeated — Campaign for Guadalupe-Lamar light rail moves ahead».)

Time and time again, Austin has demonstrated that it’s the national poster child for chronically muddled urban mobility planning. In a January 2015 post, we warned that “Austin – supposedly the most ‘progressive’ city in the ‘reddest’ rightwing state of Texas – has a distinctive (read: notorious) reputation for dithering, dallying, and derailing in its public transport planning ….” («Strong community support for Guadalupe-Lamar light rail continues — but officials seem oblivious».) As our previously-cited March 2015 post went on to observe: “The devastating befuddlement of Austin’s official-level urban transportation planning … has been nothing short of jaw-dropping.”

Will Austin, and Capital Metro, ever manage to break out of this pattern of failure? Does hope still spring eternal?

■