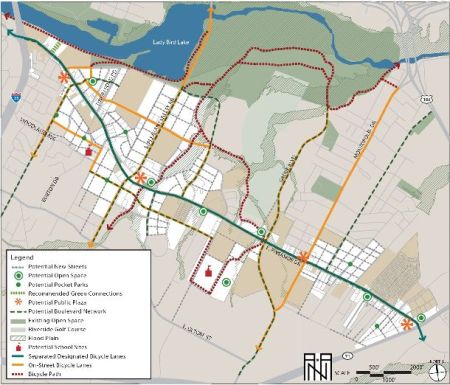

Urban rail concept started as a plan for a streetcar “circulator” system, shown in this early map from 2006. Map adapted from Austin Chronicle.

♦

To understand the roots of the Highland-Riverside urban rail plan on the ballot today, you need to understand how an official “express train” planning process, aiming to lock in an urban rail line to the Mueller redevelopment site, got derailed and sidetracked by community intervention. Here’s a very abbreviated version of the story.

Austin’s current “urban rail” planning arose ca. 2005-2006 following the November 2004 voter approval of Capital Metro’s “urban commuter rail” project, in a package (including “rapid bus” service) called All Systems Go proposing the operation of DMU (diesel multiple-unit) railcars between downtown and the suburb of Leander. The previous light rail (i.e., urban rail) plan for a line on Guadalupe, North Lamar, and the railway alignment northwest as far as McNeil had been shelved in mid-2003 in favor of the cheaper, but very bare-bones, DMU plan.

Since the newly approved DMU line ran on a railway alignment that bypassed most of the heart of the city, ending only at the southeast corner of the CBD, officials and planners realized they needed some way to connect passengers with key activity points, including UT and the Capitol Complex. The answer they devised was a “circulator” system using streetcar technology, which would intersect with the DMU line (eventually rebranded as MetroRail) and connect to downtown Austin, the east side of the Capitol Complex, the East Campus of UT, and the Mueller development site. (See map at top of post.)

But, critics asked, what about the dense West Campus neighborhood and the busy commercial district on The Drag? What about the original plan for light rail along Guadalupe and Lamar? The “rapid bus” service included in the All Systems Go package, intended as a precursor to rail in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, was then viewed only as a temporary “fix”, and it seemed clear that rail needed to be planned for that corridor as well.

Within Capital Metro, Lyndon Henry (then a Data Analyst with the transit agency) pressed the case for at least an initial rail line to serve The Drag and West Campus, and at public meetings on the proposed “circulator” Henry and others continued to raise the issue. In this period, as problems emerged with the MetroRail project, Capital Metro’s involvement in the streetcar project was superseded by the City, which assumed control. When Henry’s supervisor Matt Curtis left Metro to become an aide to Mayor Lee Leffingwell, for a brief period a West Campus spur did appear in City of Austin planning maps for the proposed streetcar. (Henry is currently a contributing editor to this website.)

In 2008, as a line on East Riverside to ABIA, with a bridge over the river into the CBD, was proposed, planners became convinced that capacity and speed required fullsize light rail transit (LRT) rolling stock. However, apparently to distinguish the emerging plan from the original, centrally routed Guadalupe-Lamar line, and to retain some of the supposed lower-cost ambience of streetcar technology, the expanded system was dubbed “urban rail”, supposedly a hybrid between a streetcar and a rapid LRT system. By 2010, the Central Austin Transit Study (CATS), prepared by a consortium headed by URS Corporation, recommended a system that stretched from the Mueller site, down Manor Rd. and Dean Keeton to San Jacinto, then south through the East Campus, across the river, and out East Riverside to ABIA. Alternative alignments were suggested, and spurs to Seaholm and the Palmer Auditorium area were also proposed as later extensions.

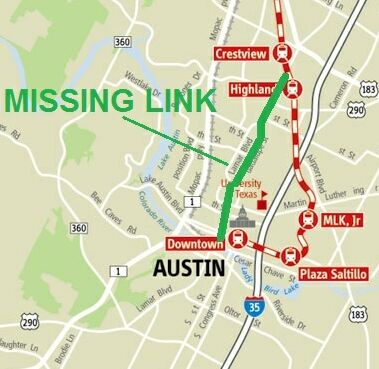

As the project made its way through the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) process, and afterward, the route structure gradually solidified; for a connection to Mueller, a preference was emerging to move the alignment from Manor Rd. to a route via Red River and Airport Blvd. But even the gesture of a spur connection to the West Campus began to vanish, prompting Lyndon Henry and the Light Rail Now Project to call attention to the need for urban rail in the “Missing Link” — the gap between MetroRail’s station at Crestview and North Lamar, and its terminus downtown. Because of that gap, not only were passengers inconvenienced by having to transfer to buses to access their destinations along the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, but also Capital Metro was running costly bus shuttles to connect MetroRail stations on the east side to the UT campus and the Capitol Complex. See: Give priority to “Missing Link”.

“Missing Link” urban rail (green), in Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, would provide the crucial connections to core neighborhoods, UT West Campus, and Capitol Complex missed by MetroRail (dashed red line). Infographic Map by Light Rail Now.

But why had the West Campus, and Guadalupe-Lamar, disappeared from the official urban rail plan? As Henry, Dave Dobbs, Andrew Clements, Roger Baker, and others persistently raised this issue, mainly at meetings of the Transit Working Group (a blue-ribbon committee of civil leaders nominally attached to CAMPO, the Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization), planners and officials under the aegis of the Project Connect public agency consortium pointed to a Route Alternatives Evaluation Process included in the 2010 CATS project that had supposedly ruled out a “University of Texas (UT) to North Central Austin (Hyde Park)” route, instead giving top scores to routes serving Mueller, East Riverside, and Seaholm — basically, what City policy actually wanted.

Scrutinizing the “Route Alternatives Evaluation”, Henry identified serious methodological drawbacks and summarized these in a commentary, City’s Urban Rail “alternatives analysis” omitted crucial Lamar-Guadalupe corridor! presented to the TWG on 27 April 2012. These problems are also discussed in our article City’s 2010 urban rail study actually examined corridors! But botched the analysis… (26 November 2013). Basically, the 2010 “evaluation” totally ignored the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, and “evaluated” an array of alternatives with subjective ratings of 1, 2, or 3. Thus, voila! The preferred official routes, including the route to Mueller, won the “competition”!

CATS map of potential rail corridors studied — but Guadalupe-Lamar was omitted! And subjective scoring system facilitated ratings that favored City’s desired route plan. Map: COA and URS.

In what seemed like an Urban Rail Express to Mueller, by May 2012, the official urban rail proposal had gelled into a Phase 1 project running 5.5 miles from downtown, through UT’s East Campus via San Jacinto, then northeast via Red River St., 41st St., and Airport Blvd. into the Mueller site. The total investment cost was estimated to be $550 million.

Finalized in May 2012, 5.5-mile, $550-million Phase 1 urban rail starter line was proposed to connect downtown, UT East Campus, Hancock Center, and Mueller site. Graphic: Project Connect.

But the constant pounding by community critics — especially Lyndon Henry’s exposé of the outrageously dubious Route Alternatives Evaluation from 2010 — was taking its toll. The result was that Project Connect placed the Mueller Phase 1 plan on hold and shifted course dramatically. In early 2013, Kyle Keahey was hired as Urban Rail Lead to head a new “High-Capacity Transit Study”, tasked with supposedly re-evaluating everything, racing through a process (with a presumably more competent and defensible methodology) that would result in a recommendation by the end of 2013.

To some, it seemed a new beginning and a possibly more hopeful and fair approach to analyzing travel corridors, particularly the heavily traveled, high-density, and widely popular Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. Unfortunately, that was not to happen. As it proceeded, it became increasingly clear that the much-vaunted “High-Capacity Transit Study” was actually a fraud. The highlights of this process will be summarized in a subsequent report. ■