By Lyndon Henry, Editor

Austin’s transit agency, Capital Metro, is currently in the process of developing its Transit Plan 2035, which it describes as a “blueprint for the future of public transportation in Central Texas” with “strategies to update transit services, upgrade infrastructure” and better meet the public’s needs over the next five to ten years. With considerable “community engagement”, the agency proposes to complete this plan by “Summer/Fall 2025”. Most recently, this effort at engagement has included a Community Meeting on 10 October 2024, followed by a live interactive Webinar on 15 October, and an online survey completed in late October.

This decade-wide plan presents an opportunity for CapMetro, in coordination with other local public agencies, to project thinking beyond the usual modest expansion of bus routes and associated facilities and to envision a considerably more robust expansion and enrichment of CapMetro’s regional public transport role and functionality. Austin Rail Now suggests this would likely involve a multi-agency effort to more aggressively utilize the possibilities of Central Texas’s rail public transport resources via three ongoing and potential major Central Texas rail public transport projects:

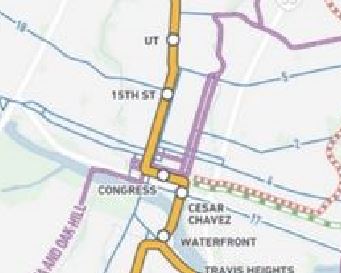

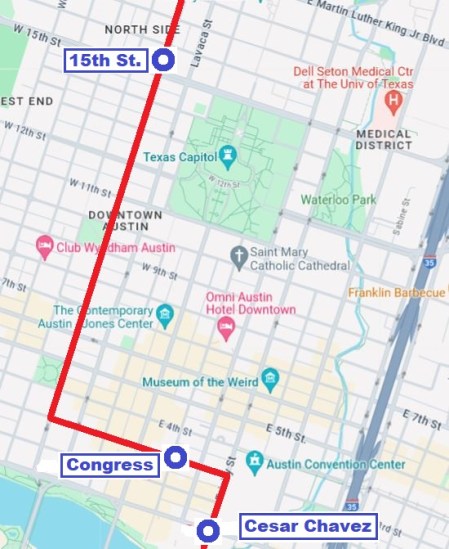

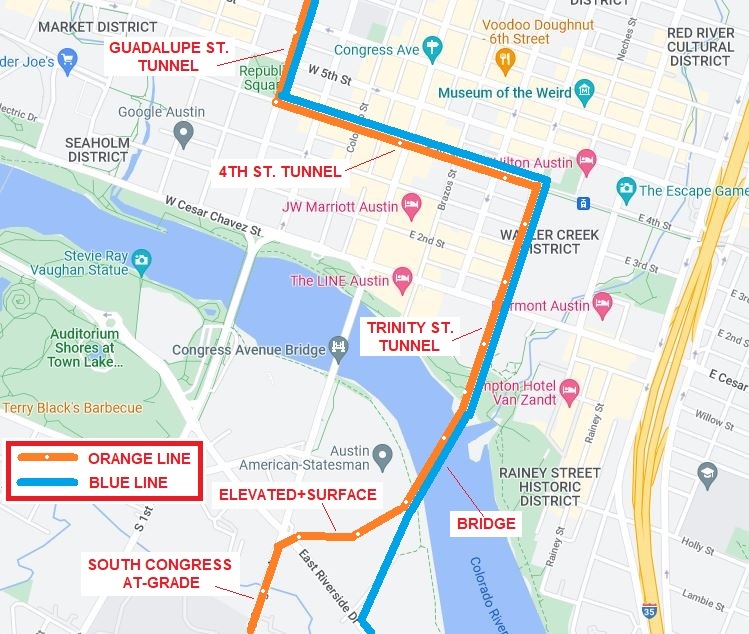

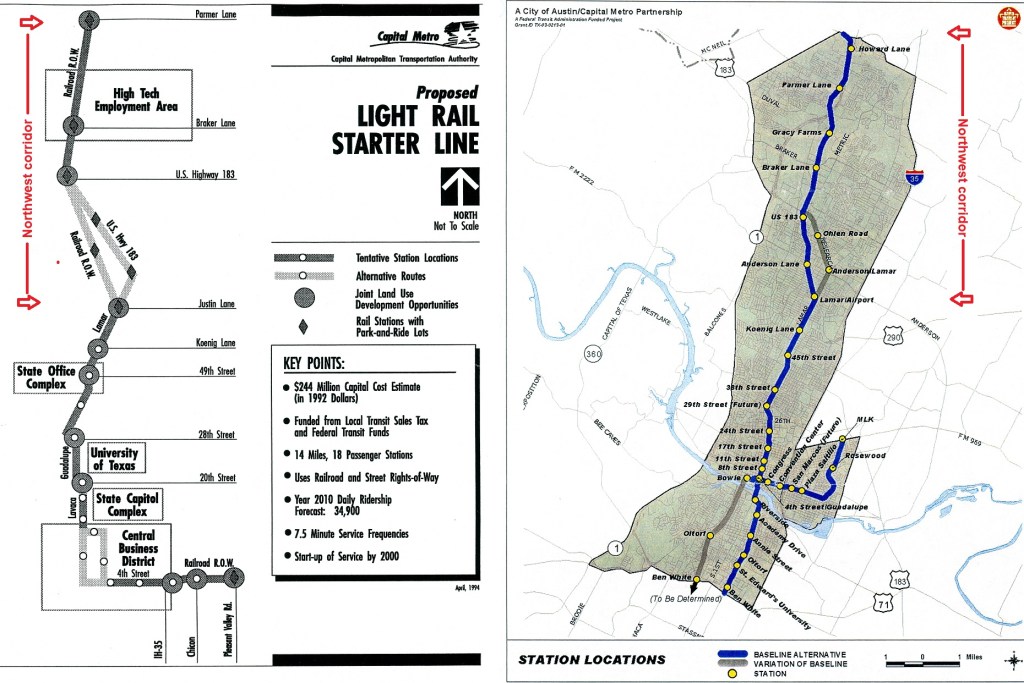

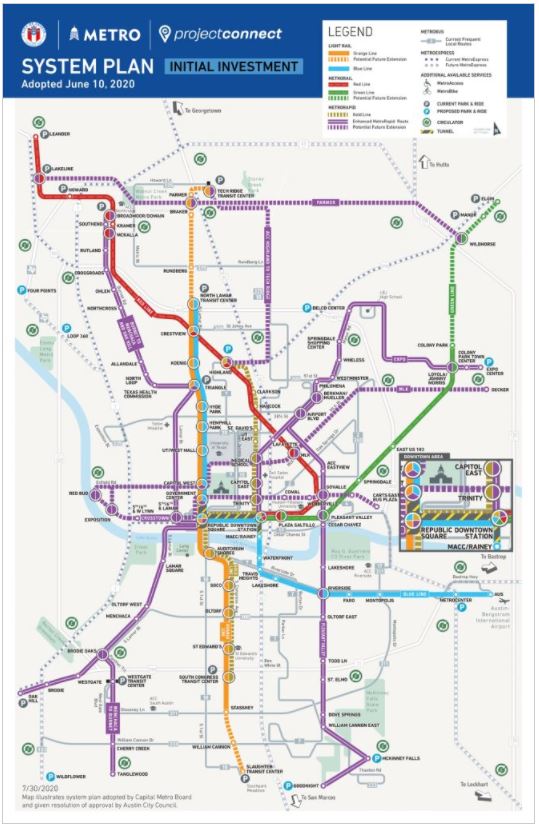

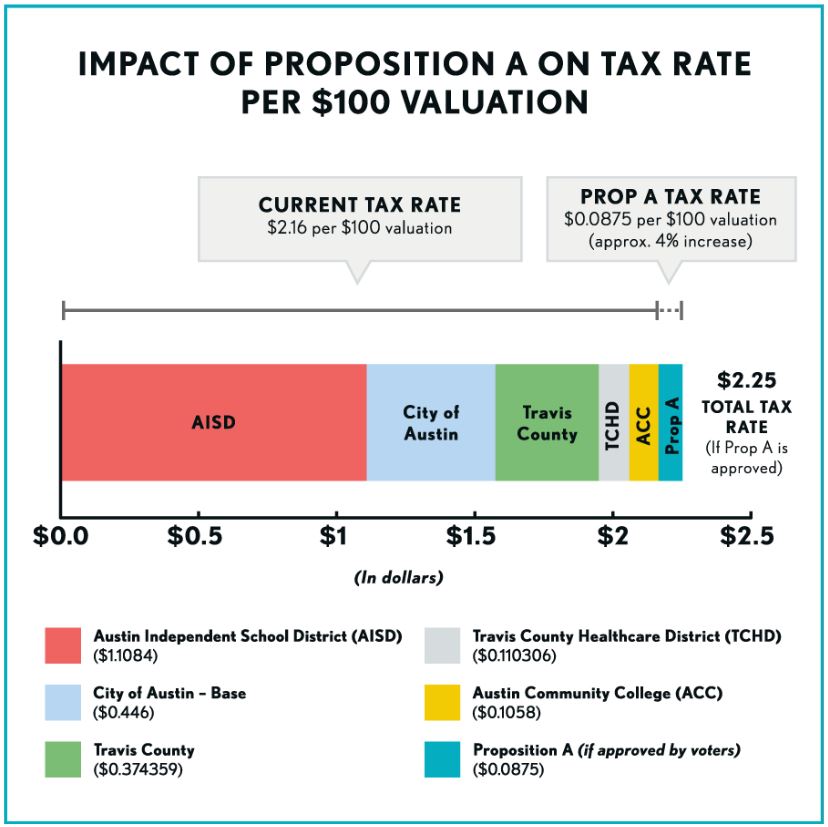

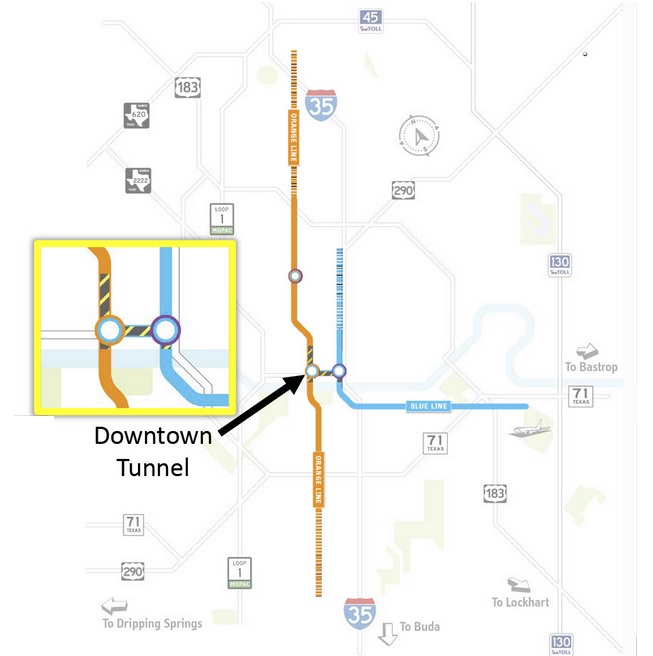

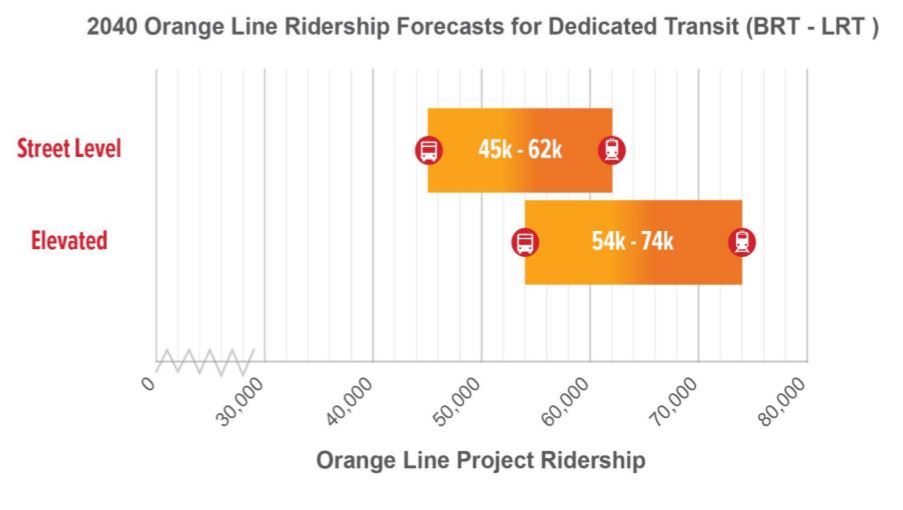

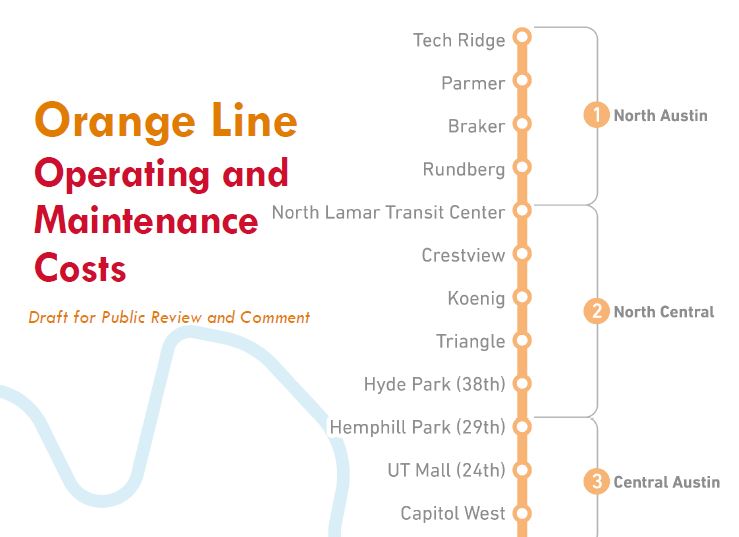

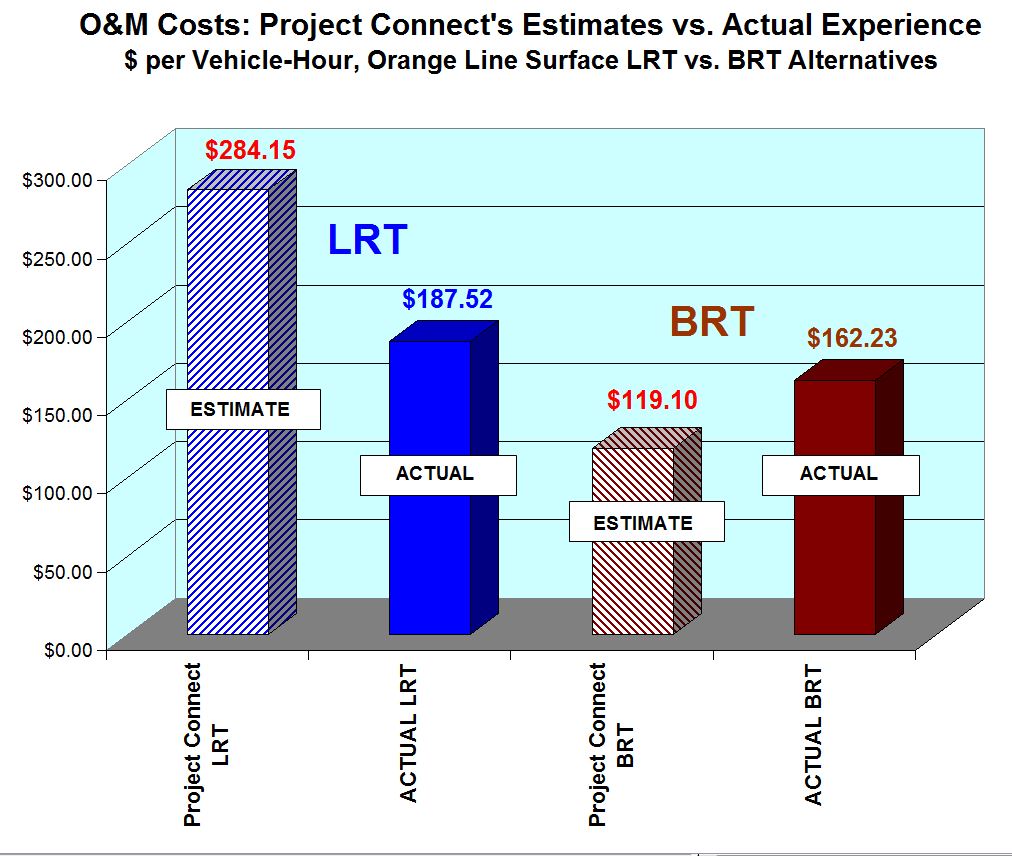

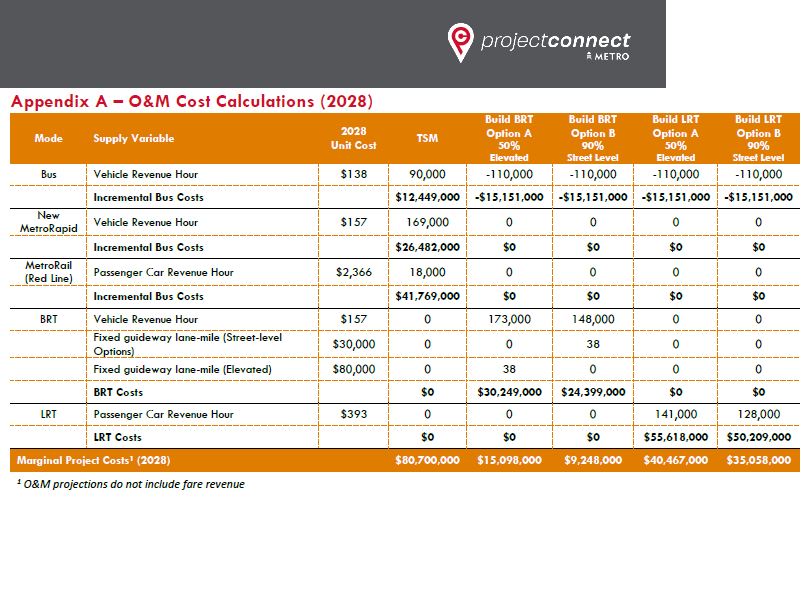

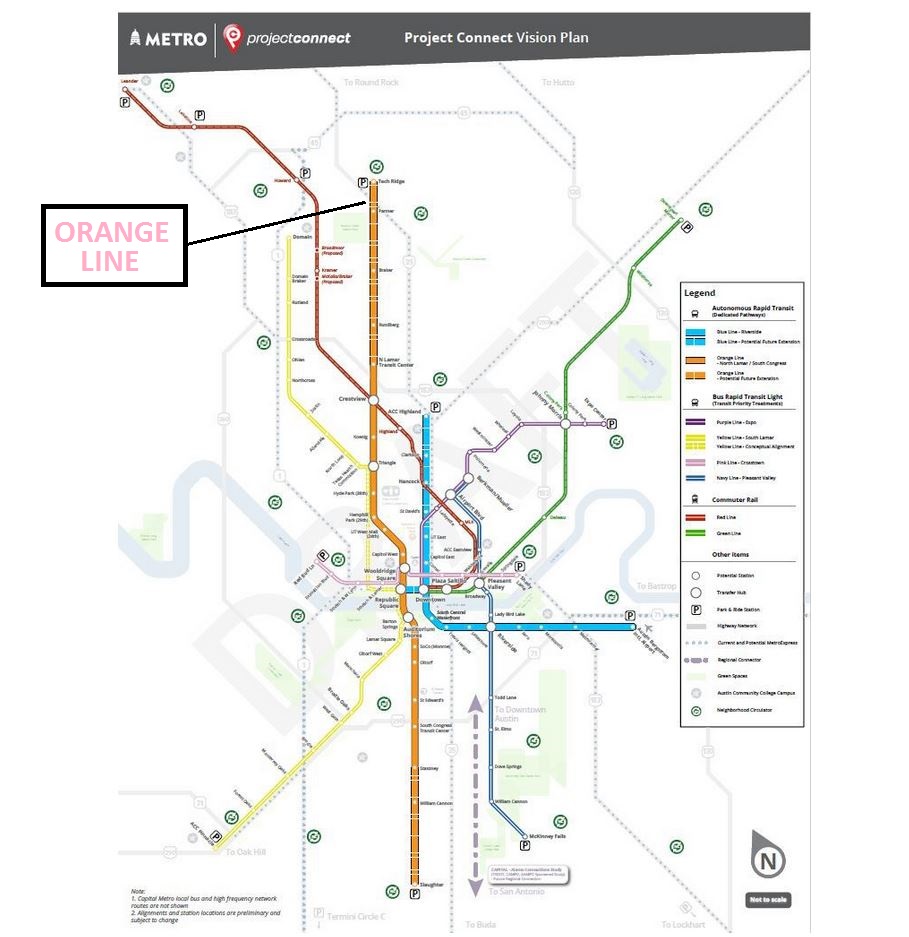

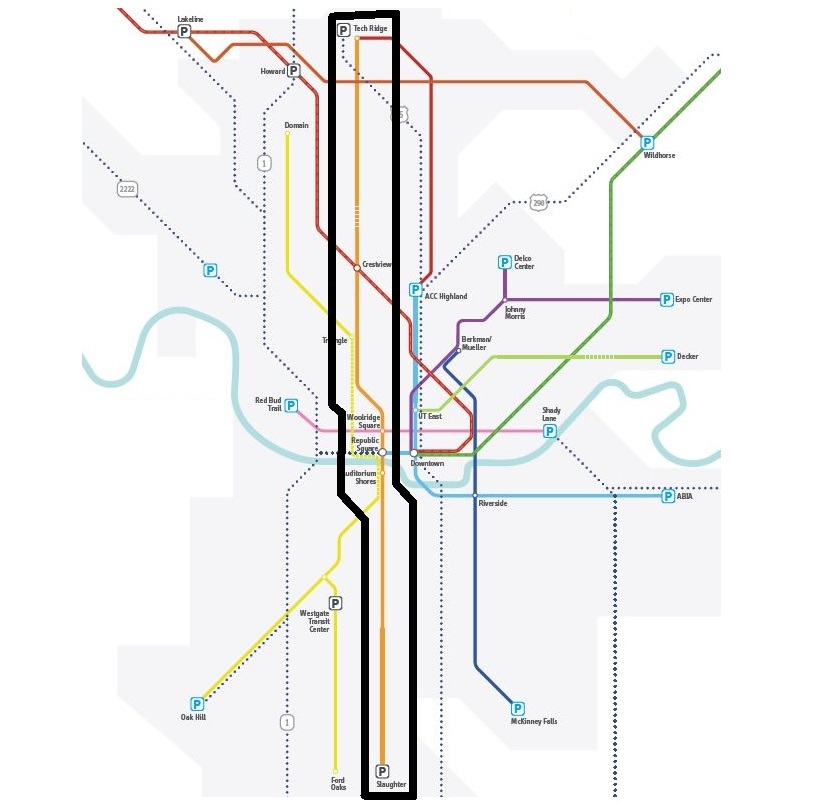

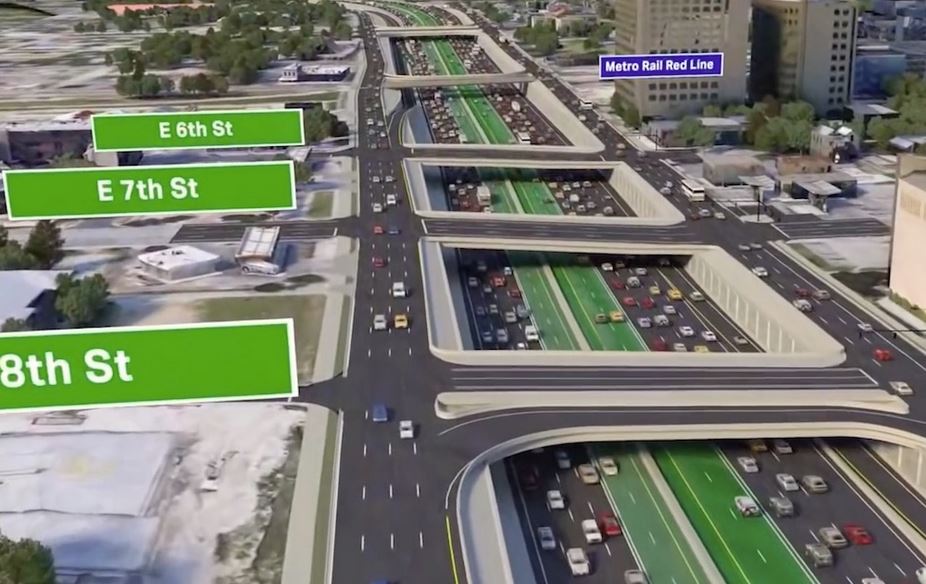

► Light rail transit (LRT) — Completing and expanding Project Connect’s initial 9.8-mile light rail transit (LRT) system, a project currently aiming for groundbreaking in 2027, is by far the city’s most critically important transportation project. This three-branch starter system is designed to connect Austin’s Central Area and UT campus with north central Austin, the East Riverside corridor, and the SoCo area of South Austin.

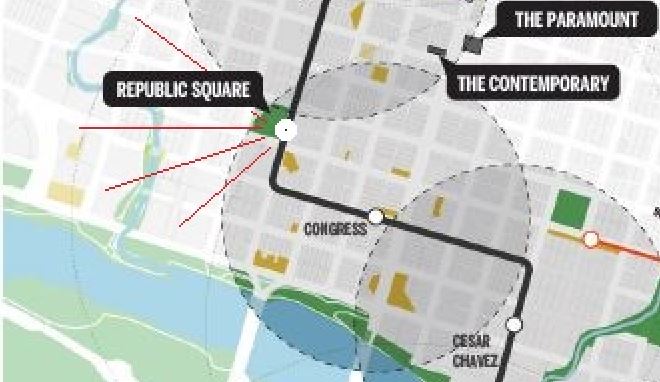

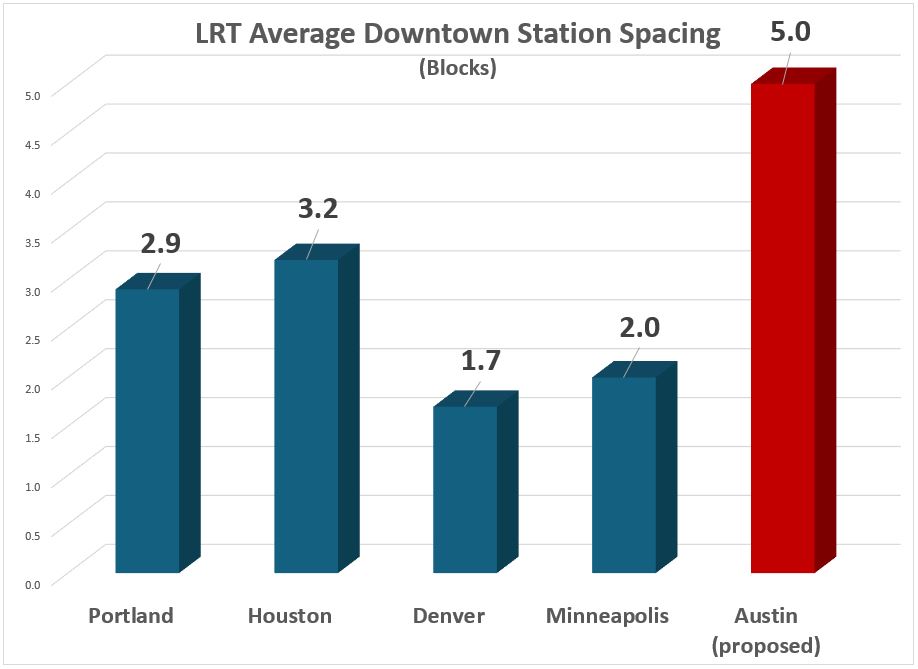

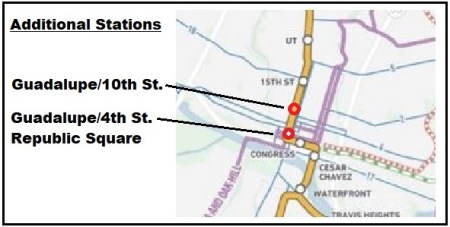

As ARN has pointed out, the most salient amendment needed by this plan is to add at least one additional downtown station – Republic Square – to this major citywide project for better population coverage and accessibility to downtown riders.

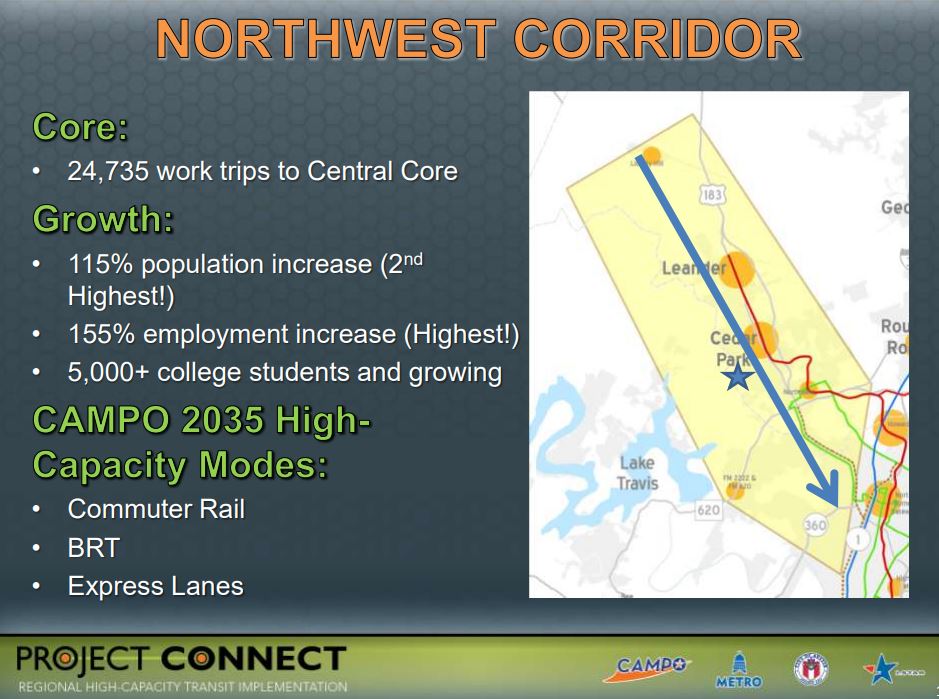

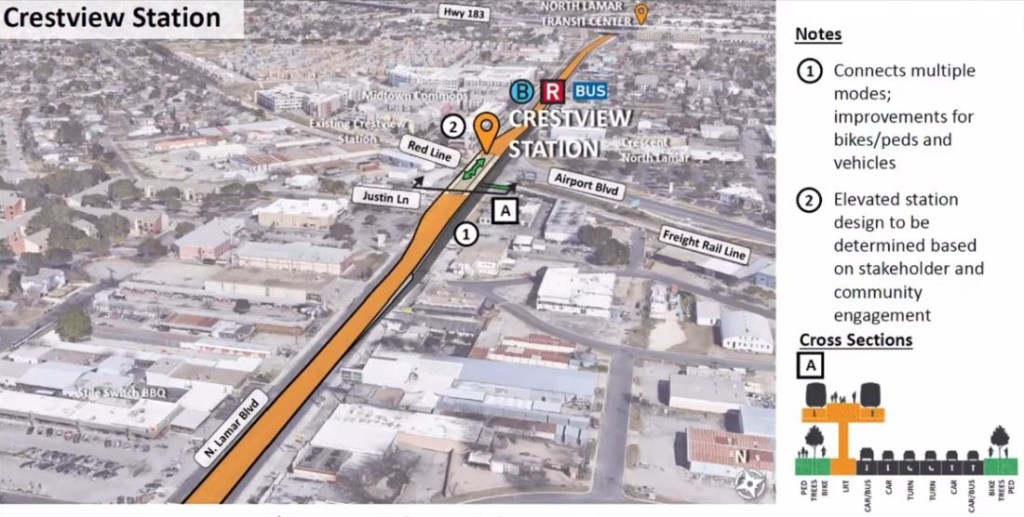

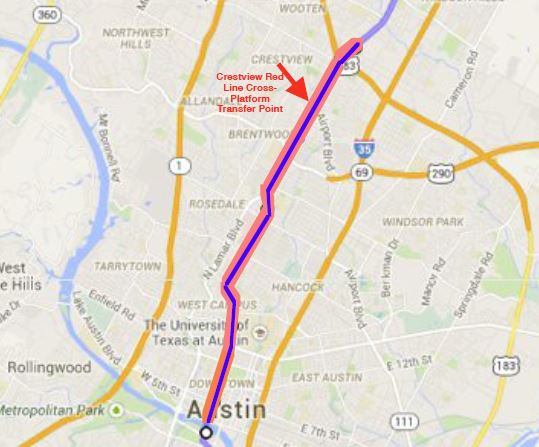

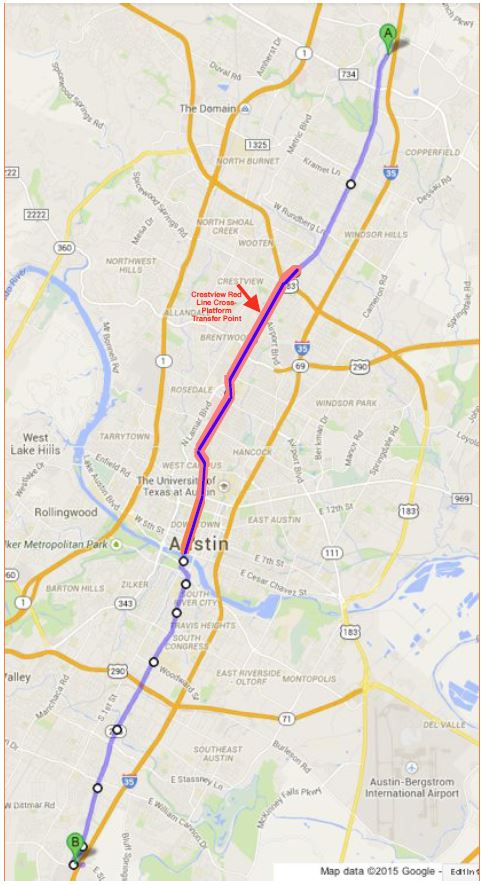

► MetroRail Red Line — This light railway, originally conceived as a precursor to electric LRT, currently operates with diesel-multiple-unit (DMU) rolling stock over a former Southern Pacific branch line running through the heart of the city, currently terminating at the Convention Center in the lower eastern side of the CBD. The service is a major potential resource but is seriously underutilized. Current headways are approximately a half-hour peak and about an hour off-peak. Trains operate on Saturdays, but there is no regular Sunday service. Current operations need to be upgraded with additional stations, more frequent headways, and 7-day service. More vigorous efforts by CapMetro and other entities are needed to encourage special “events” at stations – particularly to create and build ridership – as well as transit-oriented development (TOD, including housing plus offices, restaurants, retail stores, and other activities).

Most importantly, planning needs to be started to convert the Red Line to electric light rail and integrate it fully into the future LRT system, as we have proposed. In respect to this, our earlier analysis also addressed concerns regarding the compatibility of LRT service with CapMetro’s contracted shortline freight railroad operations:

Capital Metro’s privately contracted freight rail operation is currently an important revenue source for the agency; in addition, by reducing motor truck traffic on metro area roadways, it provides a net environmental benefit. MetroRail passenger service currently shares these tracks with freight via temporal (time) separation (freight operations run late at night, leaving the tracks free for transit service from morning to evening). LRT could operate likewise. LRT operations elsewhere also provide models and precedents for this: the San Diego Trolley (since 1981) and Salt Lake City Trax (since 1999) have successfully and safely shared tracks with freight railroad services for decades.

In addition to those precedent examples, the actual prototype for Austin’s MetroRail has been New Jersey’s River Line between Trenton and Camden, a DMU-powered light railway opened in 2004 which also provides passenger service via a time-sharing arrangement with freight operations.

► Austin-San Antonio rail — The possibility of a fast, relatively frequent regional passenger rail connection (“commuter rail”) between Austin and San Antonio, serving other Central Texas communities as well, is back on the public agenda. Community interest has even emerged to extend this regional corridor service further north, possibly to Temple, Waco, or even Dallas-Ft. Worth.

While the previous effort to create such a service unfortunately collapsed in 2016, the Lone Star Rail District (LSTAR) continues to exist as a state-authorized agency, with the power to raise funding via a tax-increment financing (TIF) mechanism. Over the past year and a half, the prospect of establishing this valuable public transport service has been revitalized as popular support efforts have re-emerged. Success would need effective leadership by a consortium of regional agencies, including the cities of Austin and San Antonio, affected counties, their regional Metropolitan Planning Organizations (CAMPO and AAMPO), their metropolitan transit agencies (Capital Metro and Via), and other key organizations.

In lieu of LSTAR’s previous (now-defunct) agreement with the Union Pacific Railroad, the most viable course forward now would rely on an Amtrak-involved participatory model (by Federal law, Amtrak has the right to use existing privately owned railroad infrastructure through negotiated coordination with privately owned freight rail operators). Examples of such regional services operated by Amtrak can be found across the USA, such as the Pacific Surfliner, Capitol Corridor, and San Joaquin services in California; the Amtrak Cascades trains serving the Pacific Northwest from Eugene, Oregon through Tacoma, Washington and Seattle, Washington to Vancouver, BC, Canada; the Heartland Flyer between Oklahoma City and Ft. Worth; the Hiawatha Service between Chicago and Milwaukee; Missouri River Runner trains between St. Louis and Kansas City; Lincoln Service trains between St. Louis and Chicago; Wolverine and Blue Water service linking Chicago with Port Huron, Pontiac, and Detroit, Michigan; Piedmont service linking Raleigh and Charlotte, NC.

In the Austin-San Antonio corridor, the proposed regional passenger service would use Union Pacific Railroad (UP) trackage. (Amtrak’s Texas Eagle service has been running over this and other heavy railroad trackage for decades, providing a daily train in each direction between San Antonio and Chicago. Any extension north of Temple would likely involve also the BNSF Railway.)

Whether just an Austin-San Antonio line or a longer route, such an operation would almost certainly require considerable public investment in additional infrastructure – additional trackage (to reinstate double-trackage where existing lines are only single-tracked) as well as stations and other facilities, such as new rolling stock and a storage-maintenance-operations facility. According to previous studies, it should be possible to cover these investments through LSTAR’s TIF revenues in combination with federal government grant programs.

If history and experience provide a guide, the benefits from such an expanding network of high-quality urban, suburban, and regional rail will more than justify major investment, foreseeing not just economic development and TOD, but especially a variety of vastly expanded, improved, and safer travel options as well as an increased diversion of trips from roads to rail. The uniquely attractive quality of fast, safe, comfortable, and understandable rail public transport has been widely demonstrated both in the USA and worldwide. Increasingly, regional planners and decisionmakers are tending to recognize the inherent value of investment both in new rail system infrastructure as well as the existing rail rights-of-way and infrastructure already in place. ■