New-Start light rail transit (LRT) systems have proliferated in cities across USA while Austin urban rail planning has languished. LEFT: Norfolk’s new LRT line opened in 2011. (Photo: D. Allen Covey.) RIGHT: Tucson’s new SunLink streetcar opened in 2014. (Photo: Tyler Baker.)

♦

Heading into 2017, in the face of a relentless and steadily worsening mobility crisis, the Austin metro area seems guaranteed to retain its notorious status as the national (and perhaps global?) Poster Child for indecision, confusion, and phenomenally incompetent transportation planning. Not only has this crisis been getting more severe … but even worse, policy decisions by local officials and planners have been reinforcing and expanding the underlying problems of suburban sprawl, a weak public transport system, and near-total dependency on personal motor vehicle transport. These have constituted the primary generators of congestion and the incessant tsunami of motor vehicle traffic engulfing the metro area … increasingly exposing the Austin-area public to hardship and danger.

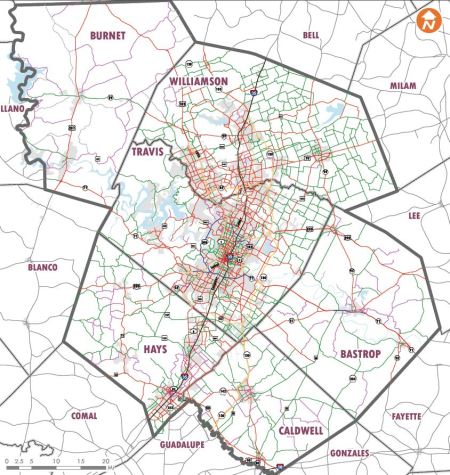

Despite years of “politically correct” affirmations of the need for public transport (including urban rail) and more livable development patterns, local public policy has consistently maintained a central focus on expansion of the roadway system and encouragement of outwardly widening sprawl. This transportation and urban development policy has been and continues to be the region’s de facto dominant, obsessive aim.

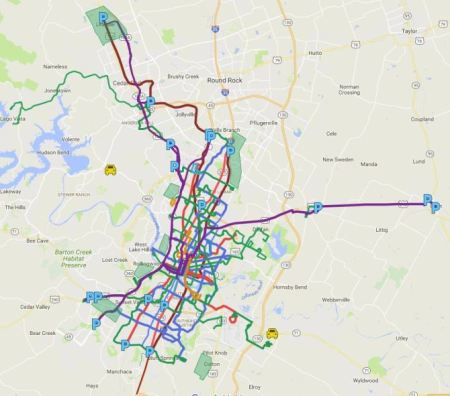

The main mechanism for formulating and implementing this objective has been CAMPO (Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization), the metro region’s federally certified mandatory transportation planning agency, with representatives from Austin, Travis County, and five other surrounding counties. In concert with the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), policy has been dominated by suburban and rural officials, assisted by the acquiescence of “progressive” political leaders representing Austin and Travis County.

In 2015, articles posted on Austin Rail Now by Roger Baker and David Orr described how CAMPO’s planning process not only implemented a determined focus on expanding roadways and suburban sprawl, but also removed light rail transit (LRT) from consideration. (Most recently, CAMPO also discarded the Lone Star regional rail plan that would have connected Georgetown, Round Rock, Austin, San Marcos, New Braunfels, and other towns and small cities with San Antonio.)

• «Baker: CAMPO’s 2040 plan = “prescription for intense and auto-addictive suburban sprawl development far into future”»

• «Austin’s “shadow government” (CAMPO) disappears light rail from local planning»

For Austin-area public transport, the result has been a malicious triple whammy: (1) A pervasive, growing network of widely available, easily accessed roadways continues to attract travel away from relatively slower, weaker public transit. (2) Sprawling roadways encourage and facilitate sprawling land-use patterns that virtually require personal motor vehicle ownership for access to jobs and essential services such as grocery shopping. (3) The enormous expense of constructing, maintaining, and expanding roadways (and associated infrastructure such as traffic signals, street lights, drainage facilities, and utilities to serve ever-spreading sprawl development) absorbs available public funds and restricts and diverts funding from public transport.

These impacts were described in our article «Austin — National model for how roads are strangling transit development» posted this past October, which also highlighted the role of the “progressive” city administration’s huge “Go Big” $720 million “mobility” bond package as an accelerant to the region’s ongoing road expansion agenda.

Relentless, obsessive focus on highway expansion by CAMPO and TxDOT contiinues to induce increasing traffic and to worsen congestion. Source: Culturemap.com.

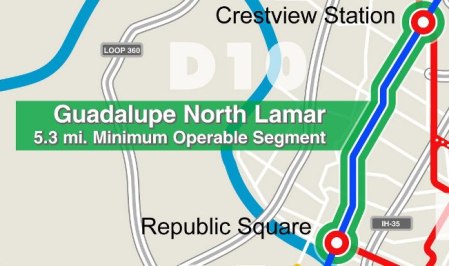

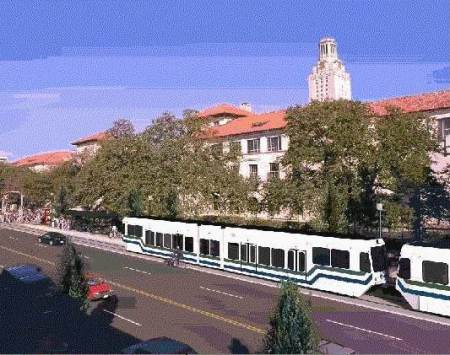

Within this environmental and policy context of continual, ferociously aggressive roadway expansion and sprawl development, how has public transit policy fared? Within roughly the past 15 years, the answer is … miserably. The pursuit of a rational, viable LRT project (i.e., affordable urban rail) in Austin’s busiest, densest central local corridor – an effort that lasted from the last 1980s until the early 2000s – has basically been abandoned in official planning.

While MetroRail (which was initially proposed in the late 1990s to demonstrate the efficacy of rail transit, and serve as a precursor to electric LRT) was endorsed by voters and eventually launched in 2010, Austin’s regional transit agency, Capital Metro, has never attempted to expand its potential. Instead, the agency has locked in MetroRail’s role as a small “commuter” line, and has ditched the original vision of conversion to LRT. The rail operation remains a relatively tiny adjunct to Capital Metro’s system, with (mainly because of low ridership) the highest operating and maintenance costs per passenger-mile of any comparable rail systems in the country.

Despite a significant legacy of planning for LRT in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor (see «Long saga of Guadalupe-Lamar light rail planning told in maps») and enduring community support for a starter LRT line in the corridor, Austin and Capital Metro officials have persistently either avoided consideration of LRT, or have pursued plans in other, far less viable corridors such as the once-favored route to the Mueller development area. (See «Derailing the Mueller urban rail express — Preamble to Project Connect’s 2013 “High-Capacity Transit Study”».)

By far, of course, the preeminent example of this has been the ridiculous Project Connect-sponsored “High-Capacity Transit” study of 2013 (see «The fraudulent “study” behind the misguided Highland-Riverside urban rail plan») and resultant absurd recommendation of a $1.4 billion Highland-Riverside urban rail “line to nowhere”. Fortunately, Project Connect’s Highland-Riverside critically flawed “urban rail” proposal was resoundingly defeated by voters in November 2014. (See «Austin: Flawed urban rail plan defeated — Campaign for Guadalupe-Lamar light rail moves ahead».)

A concomitant fiasco has been Capital Metro’s effort to portray its MetroRapid limited-stop bus service as “rapid transit”, evidently intended in part to try to deflect community interest in urban rail for the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. So how’s that effort worked out?

As the Austin American-Statesman’s transportation reporter Ben Wear pointed out this past July in an article titled «Pondering Cap Metro’s ridership plunge», “It hasn’t gone well.” Wear notes that, despite the introduction of supposed “rapid transit” service, ridership in the corridor has dropped by a third over the past four years.

Capital Metro and Austin officials have touted MetroRapid bus service as “rapid transit”. Photo: L. Henry.

Likewise, in an Oct, 26th KXAN-TV news story titled «MetroRapid ridership lags along North Lamar and South Congress», reporter Kevin Schwaller noted that current North Lamar-Guadalupe-South Congress Route 801 MetroRapid boardings, at 13,000 a day, are running about 7,000 short of the 20,000 a day projected when the service was launched in 2014.

Capital Metro, it seems, remains astonishingly clueless. As our article «Capital Metro — Back to 1986?» pointed out last month, Capital Metro’s current planning seems essentially an effort to revive plans for “bus rapid transit” on I-35 rejected back in the late 1980s.

Meanwhile, as Austin (which has been considering LRT since the mid-1970s) has been mired in decades of indecision, confusion, fantasizing, and diddling, other comparable metro areas have been moving forward vigorously in their mobility, particularly by installing and expanding new modern urban light rail transit (LRT) systems (including streetcars, which can readily be upgraded to fullscale LRT). (Dates shown below indicate year new system was opened for public operation.)

► Largest Western and Southwestern cities — The largest metro areas in America’s West and Southwest now all have LRT systems in operation. These include: San Diego (1981), Los Angeles (1990), Dallas (1996), Houston (2004), Phoenix (2008), Seattle (2009). It should also be noted that San Francisco has a legacy LRT system, based on its original streetcar system operating since the 19th century, and modernized to LRT beginning in the 1970s.

► Peer cities — This category consists of a sampling of systems in metro areas that can be regarded as peer cities to Austin, in terms of size, demographics, and other relevant features). These include: Buffalo (1985), Portland (1986), San Jose (1987), Sacramento (1987), Baltimore (1992), St. Louis (1993), Denver (1994), Salt Lake City (1999), Tacoma (2003), Charlotte (2007), Norfolk (2011), Tucson (2014), Kansas City (2016), Cincinnati (2016). We should note that Oklahoma City also has a modern streetcar project under way.

With its LRT system, opened in 1999, Salt Lake City is one of many peer cities that have sped past Austin in their public transport development. Photo: Dave Dobbs.

► Other new LRT systems — It should also be noted that new modern LRT systems have also been opened in northern New Jersey’s Hudson-Bergen corridor (2000) and Minneapolis (2004).

All in all, particularly in the face of this progress in rail transit development from coast to coast across the country, Austin’s aptitude for dithering and stagnation is breathtaking. ■