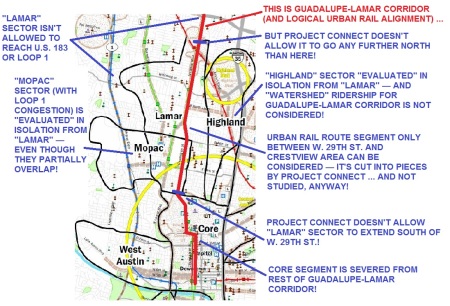

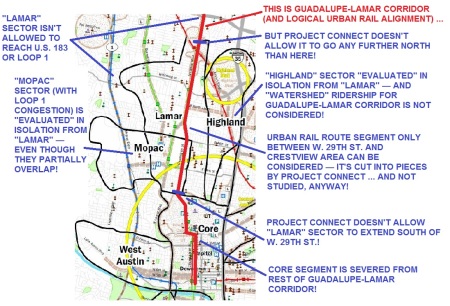

Infographic map shows several major flaws of Project Connect methodology, applied to a portion of “study” area. Result was to skew results (and urban rail route) toward desired sectors of central city. Graphic: ARN. (Click to enlarge.)

♦

Few local issues have been more divisive than the City of Austin’s 9.5-mile, $1.4 billion urban rail plan. Envisioned for a route that meanders from the Highland ACC area on the north to the East Riverside area on the southeast, the proposal is now on the Nov. 4th ballot as a $600 million municipal General Obligation bonds measure that would help fund slightly less than half of the projected investment cost.

Community skepticism — and puzzlement — about this rail project is widespread, but sponsors and supporters of it have repeatedly endeavored to bolster its credibility by describing it as the product of a “scientific”, “data-driven”, or “data-based” effort, a “high-capacity transit study” pursued by the Project Connect transportation agency consortium roughly between June and December 2013. However, as this website and numerous other critical sources have exhaustively documented, that “study” was basically a fraud.

It’s useful to review and summarize the origins of this seriously flawed rail plan as election day has come upon us. In particular, it’s important to keep in mind that the Project Connect “study” represents an object lesson in how not to conduct a study for a New Start rail transit project. This review will rely primarily on previous articles published contemporaneously on this website during the “study” exercise.

From Mueller to Riverside to Highland

As our recent article Derailing the Mueller urban rail express — Preamble to Project Connect’s 2013 “High-Capacity Transit Study” recounted, for years, local streetcar and then “urban rail” planning had focused on a starter line to the Mueller redevelopment project. There, the major urban development enterprise Catellus had been promised a rail transit link to help raise density limits, attract more property investors and homebuyers, and thus boost profits. Important also were the desires of the small but growing community of Mueller residents who expected a rail connection to jobs and other destinations.

However, for years the question had been repeatedly raised: Since the North Lamar-Guadalupe corridor was recognized as the city’s heaviest local arterial corridor, with the heaviest congestion — even used to justify the very need for urban rail in official presentations and documents — why was out-of-the-way Mueller targeted for the initial starter line investment? This inconsistency was the focus of our March 2013 article Why abandon Austin’s major corridor and congestion problem? which presented the following graphic, originally contained in a 27 January 2012 commentary by Lyndon Henry (now a contributing editor to this website):

Graphic from 2012 suggested official emphasis on urban rail line to Mueller was misplaced, when real mobility need was in Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. Infographic: L. Henry.

As our “Derailing…” article, cited above, further recounts, the City of Austin/Project Connect pretext for continuing to plan an easterly, East Campus urban rail starter line to Mueller began to fall apart when the competency of a 2010 “Route Alternatives Evaluation” — the nominal basis for the plan then current — was questioned. Possibly other factors may also have begun to come into play (such as business community interest in exploring other development opportunities that could affect urban rail route planning).

In any case, the direction of rail planning shifted significantly. As our article noted,

In early 2013, Kyle Keahey was hired as Urban Rail Lead to head a new “High-Capacity Transit Study”, tasked with supposedly re-evaluating everything, racing through a process (with a presumably more competent and defensible methodology) that would result in a recommendation by the end of 2013.

Summary assessments of Project Connect “study”

Personnel associated with Austin Rail Now, the Light Rail Now Project, and other pro-rail organizations were involved intimately in following the planning activities of the “high-capacity transit” exercise from midsummer through the early winter of 2013. A number of our articles, particularly beginning in early November, chronicled revelations and realizations about the planning process as they emerged at the time.

However, a reasonable overview of the fundamental problems with the Project Connect exercise is provided in two of our articles in particular, each of them based on major commentaries by Lyndon Henry addressed to the Central Corridor Advisory Council (a group of community leaders hand-picked by Mayor Lee Leffingwell to review and approve work of the “study” team). These two articles, from early December 2013, together represent in essence an indictment of the competency and indeed the very legitimacy of the Project Connect exercise:

• Memo to CCAG: “Pause” study or include “Lamar” sector

• Project Connect Needs an Overhaul

What emerges is the sense of a process that was corrupted and skewed to render what, in hindsight, appears to be predetermined results — results seemingly contrived to justify a routing scheme for the proposed urban rail starter line project contrived to fulfill the aims and desires of City of Austin policy and various special interests. As our article Surprise! Mayor and Project Connect select same routes they wanted in the first place (17 November 2013) assessed the process, Project Connect’s “study” seemed to have

… numerous hallmarks of having been rigged, from a peculiarly contrived methodology that departs from longstanding professional practice, to cherry-picking of a highly questionable set of data elements and the exclusion of data indicators far more appropriate for such an ostensible “corridor study”. (And, one might add, a highly secretive and insular process that immunized the ProCon team and their study procedures from public scrutiny and oversight.)

Thus the basic flaw in ProCon’s data analysis can be boiled down to one word: GIGO (“Garbage In, Garbage Out”). In effect, this appears to have been a process that involved limiting the focus to gerrymandered data sources, and then playing games with gerrymandered data.

The task facing Kyle Keahey and the Project Connect team was daunting. The prevalent public sentiment strongly favored the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor for the urban rail starter line. Most Austinites sensed that Guadalupe-Lamar carried the heaviest traffic, served the highest density, and accessed the most key activity centers in the central city. Yet the City of Austin administration, Project Connect political leadership, and a major segment of local political and civic leaders desired a “study” outcome that would validate their economic and real estate development objectives. Project Connect’s effort would therefore have to try to convince the community, “Don’t believe your lying eyes.”

PowerPoint slide in Nov. 2013 Project Connect public presentation shows audience’s overwhelming preference for “Lamar” — a proxy for the Guadalupe-Lamar travel corridor. Photo: Workingbird Blog.

Critical failings of the Project Connect “study” charade can be grouped into categories of practices. The following summaries of these practices include references to various ARN articles that may further illuminate these issues.

► Failure to examine travel corridors

Rather than zooming in on, and analyzing, actual travel patterns and density of travel in actual travel corridors within central Austin, the “study” instead carved out a great square of the central city, dubbed it the “Central Corridor” (although it contained multiple corridors in every direction), and then further subdivided this into a series of ten component sectors, some sprawling over considerable expanses of urban real estate. Since virtually the entire central city had been designated a “corridor”, these sectors were then dubbed “sub-corridors” — a kind of camouflage verbiage that masked the actual nature of what were in effect city neighborhoods or districts, not travel corridors. The “sub-corridor” designation also imparted a veneer of “transportation study” truthiness.

Our first analysis of this methodological problem, Project Connect’s “corridor” study — without corridors! noted that Project Connect’s subdivision of the study area in this way thus

… created an array of balkanized sectors that are analyzed more as autonomous geographic-demographic “islands” than as components essential to work together as a whole. As a result, actual, realistic, workable travel corridors have been obscured by all this.

Our article included a detailed explanation, with examples, of what urban travel corridors actually are, and how they should be treated and evaluated in a bona fide transportation corridor study. But, rather than corridors, Project Connect’s sectors (“sub-corridors”), we pointed out at the time, “resemble, to some extent, rather large travel analysis zones (TAZs, also called traffic analysis zones or transportation analysis zones).”

But, rather than TAZs for legitimate analysis purposes, we pointed out,

Project Connect’s sectors, in contrast, seem more designed to pit one part of the city against another — to function more as neighborhood enclaves to be assessed for their isolated demographics and “level of misery” (poverty, congestion, etc.) in a competitive showdown within a game of “Which sector deserves the urban rail prize?” It’s astounding that this charade is presented as a form of officially sponsored urban transportation planning.

Together with the agency team’s “seemingly heedless” segmentation of travel routes, their “treatment of adjacent sectors as insular, isolated enclaves, whose demographics and other characteristics apply only to themselves” was equally harmful to proper analysis. “Likewise travel characteristics are treated in isolation, as if the population in all these different ‘enclaves’ confine themselves to the sector boundaries that ProCon planners have established for them.”

Throughout the “study” process, we repeatedly returned to this problem. Our article Questions for Project Connect (3 December 2013), publishing questions which we raised in a “data dig” with Project Connect team members, asked “Why has this study avoided performing an actual corridor study, and instead spent its time (and taxpayers’ dollars) confined to undertaking a de facto inventory (and ‘beauty contest’) of various urban sectors in isolation?”

In our Memo to CCAG: “Pause” study or include “Lamar” sector (5 December 2013) we noted that “The basic methodology of focusing on sectors (so-called ‘sub-corridors’) meant that the study failed to study a single actual potential travel corridor in the study area.”

► Gerrymandered “study” sectors

Our Project Connect’s “corridor” study — without corridors! article, pointing out the peculiar boundaries applied to Project Connect’s weirdly sprawling sectors, described them as “gerrymandered”, and further experience confirmed this assessment. Our 17 November 2013 article Surprise! Mayor and Project Connect select same routes they wanted in the first place observed that

rather than performing a bona fide study of actual alternative corridors, ProCon embarked on what amounted to an inventory of highly filtered attributes of basically gerrymandered sectors, dubbed “sub-corridors”, devolving into a kind of “beauty contest” among sectors of the city, while distorting as well as ignoring the actual travel corridors that should have been the focus.

The article provides the example of the highly contrived “Highland” sector:

It should be noted that the “Highland” sector bears very little resemblance to the actual Highland neighborhood, delineated by both the Highland Neighborhood Association (see Highland Neighborhood Association endorses Guadalupe-Lamar for urban rail) and the Highland Neighborhood Planning Area defined by the City of Austin (COA). While the actual Highland neighborhood and planning district includes North Lamar Blvd. (mostly as its western boundary) all the way from Denson Drive to U.S. 183, ProCon’s “Highland” sector studiously avoids Lamar, and never reaches U.S. 183; instead, the sector incorporates I-35 (never even touched by the real Highland), and droops down far south of the actual neighborhood to include Hancock Center and the northern edge of the UT campus — thus overlapping the long-proposed Mueller route for urban rail. In this sense, “Highland” appears to be manipulated here as a kind of “proxy” for the COA’s original plan, functioning as a precursor of a full route to Mueller.

► Severed and segmented travel corridors

This was perhaps the single most serious fault of the Project Connect exercise — not only failing to examine actual corridor travel patterns, but essentially destroying intact corridors, such as Guadalupe-Lamar, simply because they crossed boundaries of the arbitrary sectors. As we first noted in Project Connect’s “corridor” study — without corridors!

Perhaps the most serious flaw in ProCon’s urban rail study methodology — actually, catastrophic, because it fundamentally impairs the integrity of the whole process — is that the actual travel corridors are not only basically ignored as workable corridors, but also are truncated and segmented by ProCon’s arbitrary slicing up of the urban area.

If you’re evaluating a travel corridor, you must evaluate the corridor as a whole — what it connects from, to, and in between; what the populations and densities along the corridor are; what activity centers it connects; and so on. All those are important, because they’re critical to what makes a transit line in that corridor actually feasible and worth investing in.

The results for the Guadalupe-Lamar travel corridor were basically fatal, as we pointed out:

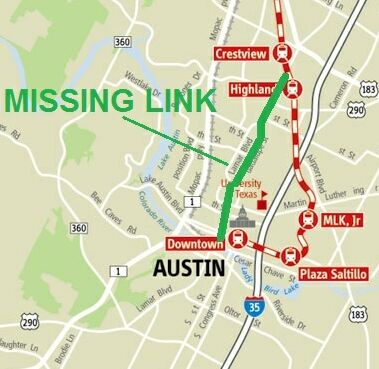

the Guadalupe-Lamar route is severed just north of the UT-West Campus area at W. 29th St. In other words, most of this potential route is cut off from its highest-density population district as well as its most productive destinations in the core of the city!

What’s left is a “rump” route, from a few blocks south of U.S. 183 to W. 29th St., that seems to have little purpose beyond perhaps some kind of “shuttle” along this isolated route segment. If there were a prize for idiotic public transport planning, surely Project Connect would be very high on the candidate list.

This problem also was repeatedly underscored. In our article Memo to CCAG: “Pause” study or include “Lamar” sector (5 December 2013) we warned that “The basic methodology of focusing on sectors (so-called ‘sub-corridors’) meant that the study failed to study a single actual potential travel corridor in the study area”, and added:

This methodology also segmented an otherwise viable corridor such as Guadalupe-Lamar into nonsensical pieces, severing the corridor from its most logical destination (West Campus and core area), and thus creating an arbitrary “rump” route (29th St. to south of U.S. 183) that goes from nowhere to nowhere.

Likewise, in Project Connect Needs an Overhaul (7 December 2013), we reiterated: “Project Connect’s methodology segmented the outstanding Guadalupe-Lamar corridor into nonsensical pieces, severing it from its most logical destination (the West Campus and core area), thus creating an arbitrary ‘rump’ route that goes from nowhere to nowhere.” These warnings, of course, were ignored.

► Excluding student and other nonwork travel patterns

While specific travel corridor trips were not examined in the “study”, Project Connect did include tabulations of total travel in each sector and estimates of trips between sectors and the Core Area. However, a particularly breathtaking aspect of the project’s Evaluation Matrix (also called the Comparison Matrix) was the exclusion of all trips except home-based work trips. In other words, non-work trips — including student trips — were omitted from consideration.

As we asked in our “data dig” Questions for Project Connect, “Why has this study’s assessment of “travel demand” from each sector to the core ignored home-based non-work (HBNW) trips — including UT student trips and recreational trips — in a college city with the largest university in Texas in its core area?”

This omission was repeatedly emphasized in subsequent articles. In our Memo to CCAG: “Pause” study or include “Lamar” sector, we pointed out:

As a measure of “Travel Demand” from each sector to the core, non-work trips such as UT student trips and recreational trips (e.g., to restaurants, bars, etc.) have been EXCLUDED — dismissing not only the enormous importance of non-work trips (which are heavy in the off-peak) for more cost-effective transit service, but especially the huge significance of student and recreational trips in a city with the largest university in the state (and located in its core).

Student travel was omitted from Project Connect’s evaluation process, although their ultimately recommended route connected UT, the state’s largest university, with ACC, the city’s major community college. Photo via UTRugby.com.

And similarly, in Project Connect Needs an Overhaul, we asked:

Extremely important non-work trips such as UT student trips and recreational trips have been EXCLUDED as a measure of “Travel Demand” from each sector to the core. How could they do this in a city whose core contains the largest university in the state?

In hindsight, the omission of student travel from the Evaluation Matrix is especially ironic in light of the fact that travel between UT and ACC would ultimately be a major component of the purported ridership of the final route presented by Project Connect.

► Manipulation of implausible projections

Skepticism about Project Connect’s heavy reliance on dubious projections began to emerge as the pace quickened toward a “recommendation” from the project team. In our 3 December 2013 article related to the “data dig”, Questions for Project Connect, we asked: “Why has this study used such speculative projections based on procedures that maximize all possible development for targeted areas (such as ‘ERC’, ‘Mueller’, and ‘Highland’), rather than using conservative projections based on conditions closer to reality?”

Local researchers and analysts such as software developer and research analyst Dan Keshet and management consultant Julio Gonzalez Altamirano had exposed serious weaknesses in the array of data projections being deployed by the project team — especially the conversion of what were in effect development “wish lists” into hard projections of future development, population, and employment that were being plugged into Project Connect’s model (an Excel-based “Evaluation Matrix” designed to competitively score the various sectors and render a winner). Their conclusions and other problems of the project’s data projections are discussed in our article What’s with Project Connect’s “2.9 million daily ridership” projection? (16 December 2013). As this article noted,

The question of projections has been an extremely contentious issue in Project Connect’s urban rail “study”. For many critics, the agency’s “projections” have represented de facto fantasies about what they would like to see, rather than the solidly reliable output of competent predictive analytics.

While projections were critical in any process of forecasting future developments and especially public transit ridership, we explained, “…there’s a vast distinction between developing conservative, reliable, and plausible forecasts, and producing exaggerated, fantasy-like projections, as Project Connect has done, heavily skewed toward certain geographical areas.”

Many of Project Connect’s “data projections” for 2030 were based on “wish lists” of development, population, employment, and other demographic features — leading critics to ridicule them as “fantasy”. Graphic via ARN.

In the 17 November 2013 article Surprise! Mayor and Project Connect select same routes they wanted in the first place, we expressed skepticism about “the selection of a predominantly questionable array of data elements as the basis for ‘evaluation’ of the various sectors. Leaving their ‘weighting’ aside, in the aggregate the evaluatory elements themselves are inappropriate.”

As the article explained,

ProCon relies very heavily on projections of future conditions for their basic measures. As the rail advocacy group AURA (Austinites for Urban Rail Action) has explained in its evaluation guide, projections themselves are basically unreliable, risky, flaky, whereas, in contrast, “We believe use of the real-world, recently-observed data gives the more accurate and reliable picture of potential ridership, as well as the greatest viability for federal funding.”

… Beyond a roughly five-year horizon, projections for specific neighborhoods and similar chunks of real estate basically become unreliably speculative — which seems to be what we’ve actually been dealing with … a significant dollop of real estate speculation, given a kind of veneer of “techiness” by CAMPO and their land use/travel demand model package.

For decades, public transportation advocates have warned repeatedly about the “self-fulfilling prophecy” syndrome in this kind of transportation planning process. In the past, it’s been applied mainly to highway development — justifying “future growth” in just the right places where developers want to build, so as to rationalize huge investments in new freeways and other roads. And, lo and behold, these very projections somehow materialize after the transportation facilities are built, thus “proving” the “validity” of the projections!

Today, in Austin, this process may be at work justifying speculative land development in certain areas of the central city (i.e., the central study area — “Central Corridor”), this time with the added drawback of ignoring or dismissing opportunities for redevelopment of areas in the heart of the core city, particularly centered along the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor.

As an example, in our article “Highland” sector favored by Project Connect — but where’s the travel demand? (19 November 2013) we noted that Project Connect’s presentation of CAMPO travel demand data in their own Map Book contradicted the claims of high travel demand in the “Highland” sector — one of the key underpinnings for their “recommendation” of a route to serve this fabricated sector. Thus, we warned, “since Project Connect based its assessment significantly on this data, the results presented, and the contrary evidence of very strong travel demand in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, contradicting Project Connect’s own stated conclusions, should at the very least raise questions about the competency and integrity of the study process.”

As we summarized the pattern in What’s with Project Connect’s “2.9 million daily ridership” projection?

Another way of saying this is that Project Connect’s planners have converted their own wishful thinking into actual data inputs, that are then deployed to make their evaluation. Wishes are used to try to make the wishes come true.

► Applying subjectively derived scores

Despite the characterization by supporters that Project Connect’s efforts were thoroughly “data-driven” and “scientific”, some components of their “study” were not even camouflaged as “projections” or externally derived data, but instead were presented merely as subjective judgements of the project team. In our 3 December 2013 “data dig” Questions for Project Connect, we asked

Project Connect’s “Physical Constraints” metric appears to be based on totally subjective value assessments, and no information has been given as to how these value judgements have been developed. Where’s the factual basis for this?

The response was that these scores were based purely on the team’s “professional judgement”. We highlighted this on our article Memo to CCAG: “Pause” study or include “Lamar” sector:

The study has assigned an extremely high “Constrained Right-of-Way” penalty to the “Lamar” sector, but not to the “Highland”, “Mueller”, “ERC” sectors — apparently implying that Project Connect considers there to be no “Constrained Right-of-Way” problems for “Highland”, “Mueller”, and “ERC”. This also is implausible, and this penalty seems to be arbitrarily applied to sectors (“sub-corridors”) that the Project Connect team dislikes (e.g., “Lamar”), but withheld from sectors they seem to prefer (e.g., “ERC”, “Highland”, “Mueller”).

► Selective manipulation of data

Another practice skewing Project Connect’s “study” results was their “cherry-picking” of data categories and their selective manipulation of their own methodology — pre-eminently, the Transit Orientation Index model they appropriated from Portland. As we explained in our analysis What’s with Project Connect’s “2.9 million daily ridership” projection? (16 December 2013):

Apparently in an attempt at a gesture toward some kind of prediction of future transit ridership, one of the metrics Project Connect decided to use in their Comparison Matrix is a “Transit Orientation Index” (TOI), a ridership demand assessment model developed in 1997 by consultants for Portland, Oregon’s TriMet transit agency. …

According to the documentation, the TOI metric is envisioned to assess transit ridership demand at the level of a small analysis zone …. Project Connect planners, however, have applied the model to considerably larger sectors covering several square miles with hundreds and even thousands of acres.

We’d previously summarized the astounding problem with the TOI model in our Memo to CCAG: “Pause” study or include “Lamar” sector, which warned that, when key projections, already embedded in the Evaluation Matrix, were plugged into the TOI,

… the results are extremely implausible — e.g., for the “ERC” (East Riverside) sector, Project Connect calculates high total daily transit ridership of 2.9 million, about equal to the total citywide daily ridership of Chicago and Philadelphia combined. (Their “low estimate” for that single sector is higher than the total citywide ridership of entire cities like Denver and Seattle.) This strongly tends to corroborate other evidence that Project Connect’s projections have been seriously exaggerated and are utterly implausible.

Likewise, in Project Connect Needs an Overhaul we observed:

Rather than developing conservative, reliable, and plausible forecasts, Project Connect has produced exaggerated, highly questionable projections, heavily skewed toward certain geographical areas. When these same projections are plugged into Project Connect’s own Transit Orientation Index (TOI), the results are ridiculously unbelievable. For the single “ERC” sector, the low-end prediction of daily transit ridership is higher than the total system daily ridership of entire cities like Denver and Seattle. On the high end, it’s about equal to the total system daily ridership of Chicago and Philadelphia combined.

These implausible outputs from the TOI were jaw-dropping. When the projections of Year-2030 population, employment, and other data items that were mainstays of their Evaluation Matrix were fed into the model, even the low-end results were absurd. For the “ERC” (East Riverside) sector, for example, as we pointed out in our What’s with Project Connect’s “2.9 million daily ridership” projection? analysis, “… the low-end figure — daily ridership of 492,682 (493K) — is equally preposterous, exceeding the total system daily ridership of entire large cities.” These cities included Portland, Seattle, Denver, and Atlanta.

As for the Highland sector, TOI results were likewise other-worldly. As we noted,

…the TOI model results for 2030 are similarly off the scale. Whereas current 2013 ridership is about 5K (5100/day), the “low” TOI prediction for 2030 is about 127K — an increase of 2,440%. The “high” prediction (no need for upper-bound substitution in this case) is 279K — a predicted increase of 5,480%.

Put another way, to meet the lower-end ridership suggested by the demographic and economic projections, average daily ridership in the “Highland” sector would have to exhibit sustained average daily ridership growth of about 7,200 each year for 17 years.

Curiously, while the project team excluded such embarrassing outputs from the TOI model from their matrix, they were selectively using other aspects of the TOI as inputs for the same matrix. As we noted,

… Project Connect’s matrix does use the TOI, itself based on the same dubious projection inputs, to render a metric score to bolster their preferred sectors (“sub-corridors”) in the competition they’ve set up. …

But, even more importantly, the TOI for 2030, dependent as it is upon Project Connect’s “projections” (de facto fantasies), exposes their absurdity. No wonder Project Connect and its entourage don’t want these used … no wonder they attempt to distance themselves from them!

It’s very simple — plug Project Connect’s own projections into this otherwise fairly realistic model, and you get bizarrely, unbelievably exaggerated results. Maybe a hint that the original projections are bizarrely unbelievable?

In effect, the TOI is performing here somewhat like a “canary in the coalmine” — telling Project Connect, and all of us, that something is terribly wrong with their demographic and economic projections for 2030.

Big Picture: Fraud

The impact of all these seemingly disconnected errors, missteps, omissions, and methodological shenanigans on a single portion of the “study” area is illustrated by the infographic at the top of this post, which focuses on several of the sectors surrounding the Guadalupe-Lamar travel corridor. (The so-called “Lamar” sector was widely misinterpreted as this corridor itself, but it was actually just a wide swath of urban real estate, stretching as far west as Shoal Creek Blvd., and embracing Burnet Road to the west as well as a segment of Guadalupe-Lamar in its eastern half — and neither of these two major travel corridors was examined.) As this graphic makes clear, the ground rules and methodology of Project Connect’s “study” very effectively prevented meaningful evaluation of this key, heavily traveled, central corridor.

From this grab-bag of colossal problems, your first assessment might be that Project Connect’s team was the rail planning equivalent of The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight. Unfortunately, it’s worse. What actually emerges out of all this, from the vantage point of a year of hindsight, is a much more troubling image than mere ineptitude — by connecting the dots, the outline of a deliberate effort to deceive and to manipulate the “study” becomes unmistakable.

Project Connect Urban Rail Lead Kyle Keahey presenting “recommendation” of Highland-Riverside urban rail route, Nov. 2013. Photo: YouTube screengrab.

Contradictory as it might seem, it’s entirely plausible that otherwise technically competent members of the Project Connect team, drawn into the “trees” of the exercise, were unaware of the implications of the larger “forest”. Also the mind, with its ability to rationalize, justify, and alibi, can be a very mysterious apparatus.

In any case, the motives for tailoring the proposed urban rail route to the needs of development policies and interests are also very clear. These are described particularly in three of our articles:

• Who are those guys? Real estate development interests and Austin’s urban rail boondoggle

• UT should pay for East Campus urban rail — not Austin taxpayers

• Derailing the Mueller urban rail express — Preamble to Project Connect’s 2013 “High-Capacity Transit Study”

So there’s motivation. There’s an amazing assortment of jaw-dropping methodological botch-ups. And it all fits together to promote the desires of the sponsors of the exercise.

The Big Picture we see of this whole process is dominated by a bright red fluorescent flashing sign. The sign says: Fraud. This is definitely a model of rail planning for other communities — a model to avoid at all costs. ■