Rendering of rebuilt I-35 at MLK Blvd. with HOT lanes for use by “Super BRT” (shown in purple and yellow). Graphic: TxDOT.

♦

The leadership of Austin’s Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority (CMTA, aka Capital Metro) seems to be rolling forward full-throttle to implement a dubiously described “bus rapid transit” (BRT) plan for Interstate Highway 35 pushed by by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) to bolster the highway agency’s massive over-$4 billion I-35 upgrade project. This mammoth project was the focus of a March 2016 posting on this website by Roger Baker and Dave Dobbs headlined «Why spending $4.7 billion trying to improve I-35 is a waste of money» (with the secondary headline «Trying to widen Austin’s most congested road will only make congestion worse»).

As that article warned,

TxDOT is far short of sufficient funds to widen I-35 with its own resources, having identified only $300 million in-house out of $4.5 billion needed. That leaves TxDOT $4.2 billion short — over 90% deficient. In fact, the Travis County section of TxDOT’s My35 redesign is still $1.8 to $2.1 billion short, which should raise red flags for local property owners who could well be targeted for big tax increases.

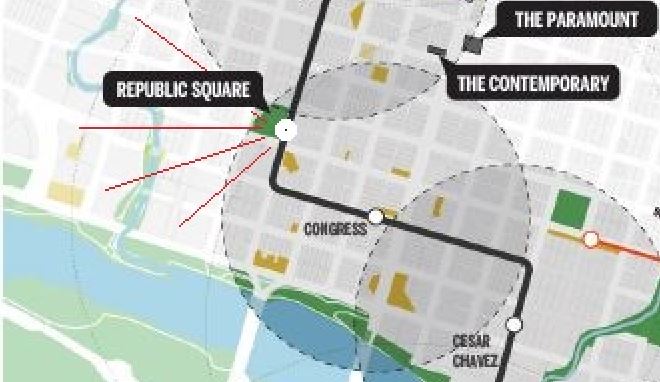

During this period, Capital Metro resuscitated Project Connect – its major planning effort ostensibly tasked with evaluating possible rail and other forms of “high-capacity transit” – to supposedly sift through various corridors, types of service, and alternative transit modes, and develop recommendations for a package of major new “high-capacity transit” investments. The process has been performed nominally with the oversight of the Multimodal Community Advisory Committee (MCAC).

Mysterious new “Super BRT” project appears

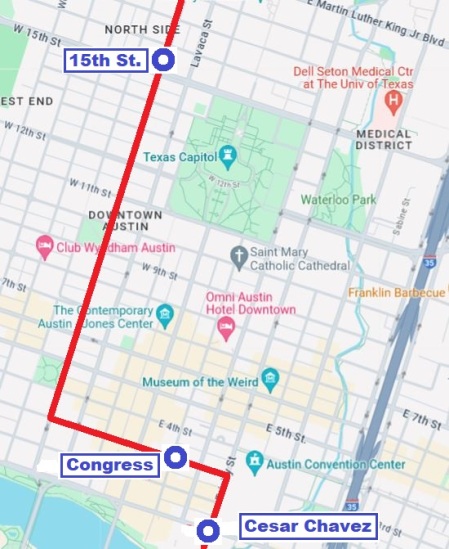

For a while the Project Connect study appeared to stay mostly on track, still focused on corridors, and just starting an evaluation of transit modes. But then it seemingly began to take a detour this past summer, when reports began to reveal TxDOT’s sudden interest in obtaining Capital Metro’s commitment to a very specific transit decision: a mysterious new “bus rapid transit” project on I-35, proposed to use High-Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes planned for the huge reconstruction of the freeway. (See graphic rendering above.) In a June 27th article Austin Monitor reporter Caleb Pritchard noted some details about the BRT plan discussed at a Capital Metro board meeting the previous evening, including TxDOT’s efforts to muscle the transit agency “to fork over $123.5 million to cover the entire cost of the [bus project] transit infrastructure.” At this, reported Pritchard, Capital Metro had “balked”, but was negotiating with TxDOT on a “counter-offer” to “cough up approximately $18 million” toward such a project and to seek other agencies (such as the City of Austin) as partners.

According to the article, Capital Metro’s vice president of strategic planning and development, Todd Hemingson, revealed that the transit agency had “been talking with TxDOT for five years about the I-35 bus rapid transit plan.”

The department is planning a $4 billion overhaul of the highway and appears to be open to the agency’s insistence that the project include some dedicated allowance for transit. The formative vision for the bus rapid transit system includes a handful of stations built on bus-only lanes in the median of the interstate. Those stations, Hemingson said, would be paired with frequent-service bus routes on intersecting east-west corridors.

…

The initial ridership projects for the proposed route between Tech Ridge Boulevard in North Austin to State Highway 45 in South Austin is between 4,000 to 6,000 trips per day.

At the meeting, Multimodal Community Advisory Committee member Susan Somers (president of the AURA urban issues community group) “raised concerns about moves that appear to make a proposed bus rapid transit system on I-35 a predetermined outcome of the Project Connect process.”

TxDOT’s arm-twisting intensified. Within weeks, the highway agency was insisting that Capital Metro had better speed up and get with the BRT program to contribute its share to the big I-35 rebuild project. Pritchard captured the situation in a subsequent July 13th Austin Monitor report headlined: «TxDOT pressures Capital Metro to act fast on I-35 transit».

As Pritchard’s report elaborated, the BRT plan emerging from the shadows already had quite a bit of detail. TxDOT wanted money to cover the cost of right-of-way “for three bus rapid transit stations to be built in the middle of the highway.”

Those three stations would be near Tech Ridge Center, at Rundberg Lane and at Slaughter Lane. The bus line that would service those stations would operate in new express lanes that TxDOT is planning to add to the freeway. The stations would allow the buses to pull out of the travel lane to allow boarding and deboarding without interrupting traffic flow. The buses would also enter and exit the highway in downtown Austin, perhaps via dedicated transit ramps, and terminate in the south at a park-and-ride off State Highway 45 Southeast.

Capital Metro VP Hemingson had also revealed that the original plan for “BRT” had been even more extensive, but had to be scaled back because of funding limitations.

Hemingson told the board that his team originally proposed to TxDOT a “super bus rapid transit” model that would have included inline stations at 51st Street, Oltorf Street and William Cannon Drive, three roads whose intersections have seen recent infrastructure investments by the state agency.

“It was kind of met with a thud, that idea,” he reported, citing its estimated cost of $400 million, or 10 percent of the roughly $4 billion that TxDOT is planning to spend on the entire I-35 project.

TxDOT’s mounting pressure on Capital Metro was corroborated on July 24th by the Austin American-Statesman. In a news report with the headline «TxDOT: Cap Metro must pay to put buses on future I-35 toll lanes», the paper’s transportation reporter Ben Wear cited the $123 million cost for the “rapid bus stations” and noted that “The agency is pressing Capital Metro for $18 million now to buy land needed for those stations.” However, reported Wear, a “Cap Metro official says the full $123 million cost is beyond its means to pay in the coming years.”

But the benefits of that $123 million investment seemed to be steadily diminishing. An August 11th Austin Monitor news update by Caleb Pritchard aptly titled «TxDOT document reveals limp projections for I-35 bus plan» reported that TxDOT had “projected less than stellar ridership numbers” for the proposed “BRT” service – at most, 3,400 boardings a day. In ridership, that would place the “rapid transit” bus line ninth among the transit agency’s other routes, well behind an assortment of more ordinary and somewhat less spectacular street-based services without heavy investment.

This tends to reflect the major disadvantages of trying to install a viable, higher-quality transit operation within a freeway. Passenger access to and from the stations – especially pedestrian access – is a distinct problem. Transit-oriented development (TOD) – particularly residential development – ranges from poor to actively discouraged. Economic development goals are unfulfilled. Yet, because of the difficulties of construction and the high land values around a freeway or tollway, capital costs are inordinately extremely high.

Yet abruptly, after months of a supposedly impartial, rigorous process of laboriously pursuing data-led solutions … Project Connect and its parent agency Capital Metro were suddenly abandoning that rigorously defined exercise, bypassing the whole process, and embracing a plan for an approximately 20-mile, $123.5-million, 3-station “BRT” line in I-35 that had actually been in Capital Metro’s planning process, albeit at a very low profile, for the past five years.

Curiously, our website (ARN) had already reported hints of such a pre-planned outcome last November. In an article titled «Capital Metro — Back to 1986?» we observed that “Austin’s Capital Metro seems determined to return to the thrilling days of yesteryear – at least in its longrange transit system planning.” A key basis for our suspicion consisted of reports from longtime Austin-area transportation activist Mike Dahmus, together with “with confirmation from other participants”, making it “clear” that “”some implementation of ‘bus rapid transit’ (BRT) on I-35 is (in the words of one observer) a ‘foregone conclusion’.” ARN had noted that this was a “revival” of a nearly identical but “faulty 1986 plan from the agency’s past.”

And additional evidence that a “BRT solution” has actually long been slated for implementation (despite an ostensible “study” process) has continued to emerge. A commentary by David Orr in ARN’s posting of Aug. 31st revealed that a Connections 2025 brochure disseminated by Capital Metro listed the I-35 “Super BRT” plan as if it were already approved as a project in line for implementation.

Minneapolis “Orange Line BRT” — a faulty model

Much of Capital Metro’s case for the I-35 “Super BRT’ plan appears to use a somewhat similar HOV-lane nominally “BRT” operation in Minneapolis as a model. Dubbed the Orange Line, the 17-mile express-bus-on-highway project is currently under development for the metro area’s I-35W corridor. However, the Minneapolis Metro Orange Line project is significantly different from what TxDOT and Austin’s Capital Metro and Project Connect are proposing. (Information regarding the Orange Line project has been obtained via discussion with former Metro planner Aaron Isaacs as well as online material from the Minneapolis Star-Tribune and Metropolitan Council.)

First, it would seem that the status of I-35 in Austin (with almost imperceptible bus service) is nothing remotely like Minneapolis’s 45-year-old, mature, heavily used I-35W transit corridor, with 25 bus routes, 14,000 daily rider-trips, and substantial existing transit investment, proposed for upgrading into the Orange Line (including one in-line station)

.

Minneapolis’s I-35W bus transit system dates from the early 1970s, when the administration of President Richard Nixon was encouraging investment in enhanced bus operations as an alternative to planning what it perceived as more expensive rail transit. In Minneapolis, this started with metered freeway ramps (controlling access to the freeway); beginning in 1972, HOV bypasses to the metered ramps were implemented, with more being added over the subsequent years. Metro also implemented bus-only shoulders on portions of I-35W and feeder highways 62 and 77.

Eventually this operation included HOV lanes (opened in 2009) used by buses. One “in-line” bus station is already in operation in the middle of I-35W.

Minneapolis Metro express-bus operation (slated for upgrade to Orange Line) has a single station in median of I-35W. Photo: Metro.

This program never produced ridership and benefit results anything close to what would be expected of a major rapid transit (or light rail) investment – a drawback that became a major factor persuading Minneapolis decisionmakers to proceed with the Hiawatha Avenue light rail transit (LRT) project (now the Blue Line) which opened in 2004. This raises the question whether it is prudent for Austin to follow a similar course of heavy bus transit investment in the I-35 corridor as its major transit option.

Secondly, the Orange Line is not intended to be Minneapolis’s heaviest major transit corridor. That role is already performed by the region’s two LRT routes – the Blue Line with 31,000 daily ridership and the Green Line with 37,000.

Third, in addition to the already-established heavy infrastructure involved in the Orange Line project, it’s relevant to note all the additional infrastructure in terms of surface dedicated lanes that exists and is being expanded with this project. Downtown Minneapolis already has an entire bus mall. This infrastructure is essential to support the heavy volumes of buses the transit agency channels through downtown Minneapolis. (Fortunately, LRT absorbs a huge portion of the total transit volume and handles this more efficiently with trains.) Are the City of Austin and Capital Metro prepared to include this level of downtown infrastructure investment in the project package in addition to the proposed “super BRT” on I-35?

Finally, it’s important to realize that a “BRT” project nearly identical to what Project Connect is now proposing was proposed and rejected in the late 1980s, in favor of LRT on a somewhat parallel route (including Guadalupe-Lamar). The main reason: the high capital cost of inserting this heavy infrastructure into the narrow I-35 freeway corridor. The proposed high volume of buses (with traffic implications for the Core Area) was also a factor in the elimination of this alternative.

Fake “BRT”, “Super” or otherwise

As one takes a broader view of this entire issue, it is legitimate to question whether it is valid to consider buses running in HOV or HOT (high-occupancy toll) lanes as “bus rapid transit” (BRT) at all.

One of the key criteria specified for “true” BRT has been having a right-of-way or alignment clearly designated as exclusive for the bus-only operation. The basic argument behind this has been that to emulate rail systems, all of which have a defined trackway that passengers know identifies the rail line (especially surface LRT), the BRT operation must have a correspondingly uniquely identified alignment reserved for its exclusive use. This is important in order to (supposedly) impart a comparable sense to passengers and the general public of the presence of the route and where it goes – i.e., a crucial factor in orienting passengers and the general public to this service. An HOV tollway open to general mixed-use traffic does not provide this characteristic.

Furthermore, the TxDOT/CMTA proposal for I-35 “BRT” would have the “rapid transit” buses leave the freeway entirely to serve most stations off the “highspeed” facility. That certainly would seem to violate the concept of a readily understandable, visually clear “rapid transit” route. Not to mention putting a big dent in travel time.

And some final considerations: With three proposed “inline” stations over about 20 miles, the I-35 “BRT” would have an average station spacing of about 10 miles. What “rapid transit” line in the world has station spacing averaging 10 miles? BART (which has some of the function of a commuter rail as well as rapid transit) has an averaging spacing of about 2.8 miles, and that’s unusually long. The next in line, the Washington Metro, averages 1.4 miles.

Our own conclusion: What’s being promoted as “BRT” – bus-style “rapid transit” – on Austin’s I-35 would be basically just a commuter bus operation, with some added amenities.

LRT makes more sense

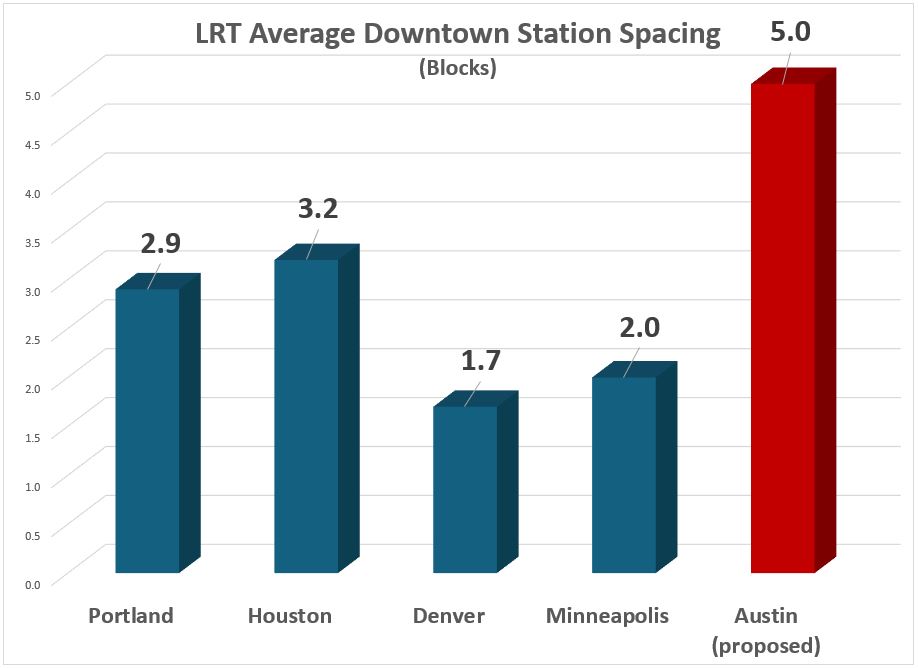

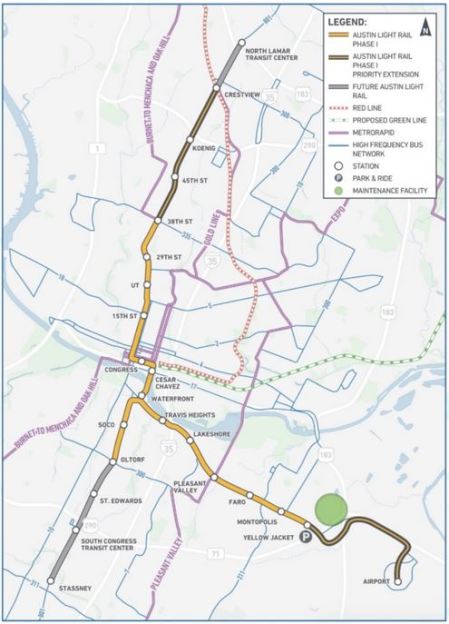

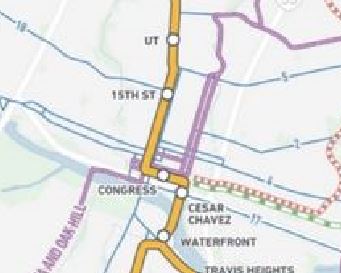

There’s a far more attractive, effective, workable, beneficial, and ultimately affordable public transport alternative to the TxDOT-Capital Metro-Project Connect express-bus plan packaged as “Super BRT”. This alternative is LRT – specifically, as ARN proposed in our July 31st article «Urban Rail on Guadalupe-Lamar, Not I-35 “BRT”» – a 21-mile LRT line paralleling I-35 but serving the center of Austin.

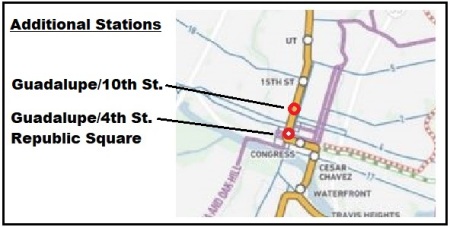

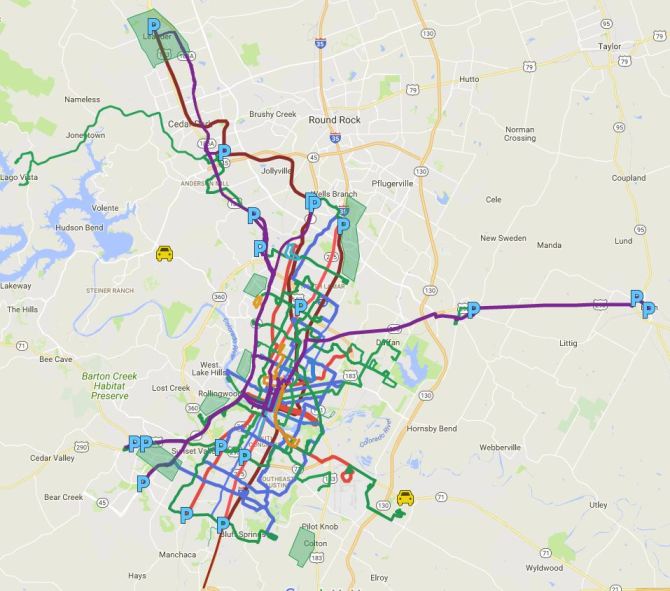

Running from Tech Ridge in the north to Southpark Meadows in the south, mainly via North Lamar, Guadalupe, and South Congress, such a line would offer dozens of stations and immensely greater accessibility, available mobility, attractiveness, ridership, and benefits to the community.

Proposed LRT running in Guadalupe-Lamar and South Congress corridors from Tech Ridge to Southpark Meadows, paralleling I-35. Graphic: ARN.

As our July 31st article indicated, the first segment should be a “starter line” in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor:

Guadalupe-Lamar (G-L) is the center city’s 3rd-heaviest north-south corridor. In addition to major activity centers, the corridor serves a variety of dense, established neighborhoods, including the West Campus with the 3rd-highest population density in Texas. With Austin’s highest total employment density on Guadalupe-Lamar, an urban rail line could serve 31% of all Austin jobs.

An initial 6 or 7 mile LRT starter line from U.S. 183 or Crestview to downtown could serve as the initial spine of an eventual metrowide system, with branches north and south, northwest, northeast, east, southeast, west, and southwest.

This kind of investment in LRT would appear to represent a far greater value for money, with potential for a much higher ROI (return on investment), than even a lower-cost express-bus project such as that proposed by TxDOT and Capital Metro, and it surely deserves a fair and impartial evaluation through the legitimate Project Connect study process. The attempt to ram through a “rush to judgement” for TxDOT’s “Super BRT” plan (evidently aimed in part to obtain Capital Metro’s buy-in for the I-35 mega-project) deserves to be jettisoned.

■