Austin City Council votes unanimously for proposed “Go Big” $720 million roads-focused bond measure on Aug. 11th. Photo: Screen capture from ATXN video.

♦

Despite intense community support and effort, particularly by transit advocates, on August 11th the Austin City Council ignored pleas to include a nearly $400 million bond item for light rail transit (LRT) on the November 2016 ballot. The administration’s own so-called “mobility” bond proposal, a $720 million package dubbed “Go Big”, without any major transit projects included, was passed unanimously. The package is “five times larger than any transportation bond ever approved in the city” according to an August 18th report by the Austin American-Statesman’s veteran transportation reporter Ben Wear.

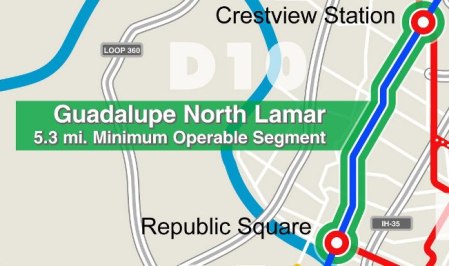

The community-proposed transit measure would have provided a local funding share for a 5.3-mile LRT starter line minimum operable system in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. (See «Grassroots effort proposes small light rail starter project for an authentic “mobility bond” measure».)

However, the seeming unanimity of the preliminary Aug. 11th vote apparently masked conflicted attitudes and misgivings of several councilmembers, simmering just below the surface. During preliminary discussions on an earlier item dealing with a proposed commission to evaluate and recommend future bond items, Councilmembers Ann Kitchen (District 5) and Delia Garza (District 2) – both transit supporters who sit on the board of Capital Metro (the regional transit agency) – floated the possibility of a rail bond ballot item in 2017 or 2018.

As reported by Caleb Pritchard in the Austin Monitor, in the discussion of the current bond proposal for 2016, District 4 Councilmember Greg Casar raised the possibility of light rail, stating “I recognize that there is some real support for public transit in the $720 million plan currently on the table, but I think that given this presidential election, it would be great to do more.” Mayor Pro Tem (and District 9 Councilmember) Kathie Tovo also tried to open the door for an LRT bond measure, but she was alone in stating she would be favor such an action, “if that was the will of the Council.”

Pritchard’s report continued:

Council members Delia Garza, Pio Renteria and Kitchen, along with Adler, also all voiced support for light rail as a concept. However, each said that the timeline is not compatible with the formal planning needed. Each said they would support a renewed light rail effort in 2018.

As previously noted, the “Go Big” roads-focused bond measure was approved unanimously at the first reading on Aug. 11th. However, a week later, in the final Council vote on August 18th, at least some disagreements came clearly into the open when four councilmembers failed to support the measure – reportedly, an unprecedented fracturing with respect to a bond item, for which council votes have historically been unanimous. As the Statesman’s Ben Wear observed in an Aug. 19th followup story, “Having a split council vote on bond packages is not how these things go historically, and it doesn’t bode well for passage by voters.”

The nonsupportive votes broke down as three abstentions and one opposition. Although the “Go Big” package was primarily a roads measure (designed to “increase throughput” of traffic, according to its proponents), right-leaning pro-highway Councilmembers Don Zimmerman (District 6) and Ellen Troxclair (District 8) – who tend to be disdainful of public transit – abstained because of what they perceived as a lack of transparency with respect to the property tax impact.

District 2 Councilmember Delia Garza – as noted, a transit supporter – also abstained. As she explained, “I have concerns about the bond capacity, the bond fatigue in our community and that there are no direct improvements to public transit.” (Reported by the Austin Business Journal.)

The strongest opposition came from District 1 Councilmember Ora Houston. Houston, who is black, seemed particularly outraged at the lack of more diverse representation in the process of developing projects included in the bond package. “I am dismayed that a $720 million bond that is on the November ballot is a product of the way things have always been done …” she said, as quoted by Ben Wear in the Aug. 18th Statesman. “I feel like I’ve been bullied …” she added.

Councilmember Ora Houston in City Council meeting of Aug. 18th, during which she was only councilmember to vote against proposed “Go Big” bond package. Photo: Screen capture from ATXN video.

Wear further reported Houston’s view that “the studies that led to the ‘smart corridor’ projects arose from the old citywide-elected council and were heavily influenced by a core of central city activists rather than a more representative sampling of Austinites.” In his Aug. 19th article (previously cited above), Wear elaborated her complaint that “public input” on the content of “mobility bonds” presented to voters had been “the spawn of the bad old days of a council that was beholden to white, central city urbanites who dominated elections, and tended to cater to that clique’s policy desires.”

The roads-focused bond item now slated for the Nov. 8th ballot seems to have the role of an adjunct to TxDOT’s ambitious plans for a mammoth overhaul to I-35. As Roger Baker and Dave Dobbs pointed out on this website this past March in their critique «Why spending $4.7 billion trying to improve I-35 is a waste of money», at best, trying to “solve” congestion with more roadway facilities – thus encouraging more traffic – is a fool’s errand. And TxDOT, with local political allies, facing a daunting $4.7 billion potential cost, has been seeking to get Austin-area taxpayers on board. Particularly through some cost-shifting, the $720 million “Go Big” bond plan seems to have a role in this larger scheme.

Nevertheless, given evidence of nominal support for urban rail by Mayor Steve Adler and a majority of members of Austin’s City Council, advocates of an LRT starter line for Guadalupe-Lamar are looking hopefully to a possible rail bond measure in 2017 or 2018. But this may be a treacherous path, especially since Capital Metro board members/Austin Councilmembers Kitchen and Garza place a lot of stock in the “Central Corridor analysis” Capital Metro has in process. And once again, that “study” is positioned under the rubric of Project Connect – the same consortium of agencies that produced the disastrously flawed Highland-Riverside urban rail proposal resoundingly rejected by voters in November 2014.

Local community activists and transit advocates still have bitter memories of Project Connect’s “high-capacity transit study” process, particularly from the last five months of 2013 (and embellished during the bond vote campaign in 2014) – an exercise in subterfuge with its deeply flawed methodology (designed to justify a preordained agenda) and outrageous sham of “public involvement” (substituting “art galleries” and “clicker” feedback for bona fide meetings and involvement). For background information on that experience, see:

• The fraudulent “study” behind the misguided Highland-Riverside urban rail plan

• City Council to Austin community: Shut Up

In our article titled «Austin: Flawed urban rail plan defeated — Campaign for Guadalupe-Lamar light rail moves ahead», and posted immediately after the 2014 defeat of Project Connect’s plan, Austin Rail Now warned :

This vote also represents not only a rejection of an unacceptable rail transit proposal, but also a protest against the “backroom-dealmaking” modus operandi that has characterized official public policymaking and planning in recent years — a pattern that included shutting community members out of participation in the urban rail planning process, relegating the public to the status of lowly subjects, and treating us all like fools. Leaping immediately into a process of community inclusion and direct involvement is now essential. The community must become re-connected and involved in a meaningful way.

So far, with their latest venture into a “Central Corridor” rail study, there is no evidence that Capital Metro administrators and planners have learned appropriate lessons from the 2013-2014 debacle. As this new study moves forward, community activists and public transport advocates deserve to be extremely wary, and to be prepared to do whatever they can to avoid a replay of that previous experience at all cost. ■