Trying to widen Austin’s most congested road will only make congestion worse

Austin’s I-35 traffic congestion — bad and predicted to get much worse. Photo: Culturemap.com.

♦

By Roger Baker and Dave Dobbs

The purpose of this analysis is to document the strong case against widening roads like I-35 (Interstate Highway 35, aka IH-35) to relieve congestion, especially when there are much smarter ways to use the same public money to solve transportation problems. This concept is important to understand because TxDOT (Texas Department of Transportation) is now actively planning to increase the lane-miles and vehicle capacity of I-35 along the San Marcos to Georgetown stretch of I-35 at a cost of $4.7 billion. This road section is ranked as the most congested corridor in Texas.

There is now a near-consensus by transportation experts that trying to relieve congestion by building and widening roads in very congested cities, like Austin, will actually worsen congestion. Severe congestion throughout a city during peak hour means that traffic will seek out and fill up any new freeway capacity as fast as it can be added. As discussed in a report by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group (USPIRG), the Katy Freeway in Houston, I-10 demonstrates this fact.

In Texas, for example, a $2.8 billion project widened Houston’s Katy Freeway to 26 lanes, making it the widest freeway in the world. But commutes got longer after its 2012 opening: By 2014 morning commuters were spending 30 percent more time in their cars, and afternoon commuters 55 percent more time.

In fact, it has been known for some time that building and widening roads doesn’t relieve congestion, but with urbanization, economic prosperity, and easy-guaranteed credit reinforced by automobile-centric federal transportation policy, the familiar American car-based suburban sprawl land pattern happens automatically. Rings of suburbs ever further from a city’s core inevitably lead to severe traffic congestion in every major USA city, Austin being no exception.

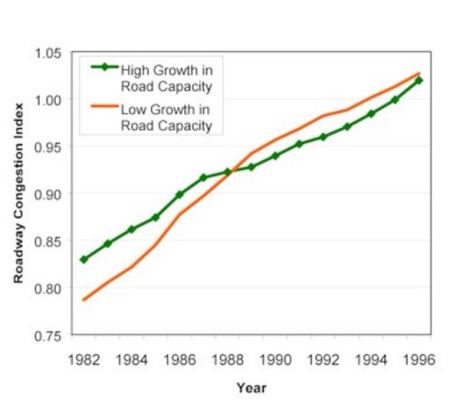

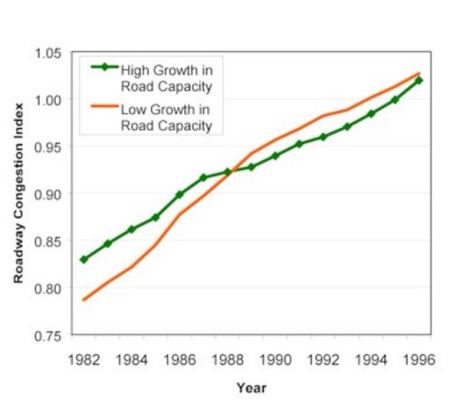

For decades, the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) at Texas A&M University has effectively functioned as a pro-road think tank friendly to TxDOT and the Texas road beneficiaries. Understandably, until recently, TTI has been reluctant to admit that building more roads didn’t actually relieve congestion, which is a counter-intuitive outlook. However, using TTI’s own data, the reform-minded Surface Transportation Policy Project (STPP) was able to document this situation back in 1998:

By analyzing TTI’s data for 70 metro areas over 15 years, STPP determined that metro areas that invested heavily in road capacity expansion fared no better in easing congestion than metro areas that did not. Trends in congestion show that areas that exhibited greater growth in lane capacity spent roughly $22 billion more on road construction than those that didn’t, yet ended up with slightly higher congestion costs per person, wasted fuel, and travel delay. The STPP study shows that on average the cost to relieve the congestion reported by TTI just by building roads could be thousands of dollars per family per year. The metro area with the highest estimated road building cost was Nashville, Tennessee with a price tag of $3,243 per family per year, followed by Austin, Orlando, and Indianapolis.

TTI Roadway Congestion Index (Mean) shows that roadway congestion has continued to rise despite intensive investment in capacity expansion. Graph: STPP.

David Dilworth, in a 2012 posting, did the following review of the basic reasons why you can’t pave your way out of congestion, and what happens when you attempt it anyway.

1) There is now overwhelming evidence, including a nationwide study of 70 metropolitan areas over 15 years (Texas Transportation Institute), and another California specific study (Hansen 1995, which included Monterey County) that when an area is congested – additional lanes or roads do not provide congestion relief.

2) It is also well documented that additional lanes increase traffic, and that new highways create demand for travel and expansion by their very existence.

3) Further experience shows “When road capacity shrinks — So Can Traffic”; traffic congestion goes down!

So, when a road is congested, adding more lanes or roads will not relieve congestion, but will likely increase traffic.

When a road is congested the only way to relieve congestion is not by building more roads, but by reducing land use – or paradoxically by closing roads.

Closing roads and reducing land use clearly implies that planners will need to rethink mobility, i.e., moving people rather than cars, and finding ways to reduce travel distances so that walking, biking, and transit become the preferred alternatives.

Nowadays, even TTI has admitted that I-35 can’t be fixed in any meaningful sense. True, some lane capacity can be added, and an urban-friendly design could mitigate its impact on the center city. However, nothing will significantly address congestion as the following excerpts taken from a recent TTI report indicate.

…This modeling research demonstrates that Central Texas cannot “build its way out of congestion” on IH 35. Examination of the initial set of scenarios demonstrates that, as capacity is added to IH 35, traffic moves to IH 35 from other streets and roads that operate with even worse congestion, in essence “re-filling” the road. As described above, Central Texas drivers fill any capacity added to IH 35. Therefore, additional capacity provides little relief to peak-hour IH 35 general purpose lane congestion. And, because population and jobs are projected to grow so much in the corridor, any open road space created by new lanes is quickly filled. …

The study team concluded that this effort demonstrates a very unlikely future. That is, the levels of congestion predicted for IH 35 — in fact, the Central Texas region — will be unacceptable for local residents and business. In discussions with the MIP Working Group regarding these technical results, there is heightened concern that the levels of congestion demonstrated by this study would dampen the area’s growth in population and employment because people and businesses will quite simply not move here if the transportation infrastructure is insufficient to avoid this level of congestion. Therefore, with impacts predicted to be this substantial to quality of life and economic health, such levels of congestion will likely be unacceptable to future residents and businesses, so that the area’s growth is in fact, unsustainable….

I-35 congestion, considered worst in Texas. Texas Transportation Institute has concluded that “additional capacity provides little relief…”. Photo: TTI.

Despite this, TxDOT is greenlighting the My35 Capital Corridor project even though it has no clear idea of where most of the money to widen I-35 will come from, and likewise the Texas Transportation Commission is authorizing funds piecemeal to construct parts of the full-blown I-35 vision in TxDOT’s District 14, Austin, where $158 million has been allocated for this year (as reported by the Austin American-Statesman).

This question remains. Why should we be planning a traffic solution which we know in advance will make I-35’s daily bumper-to-bumper congestion a lot worse, and which will make us more dependent than ever on fossil fuels, even while knowing that the money to do this isn’t there? And why would we rush to judgement in November, at least for I-35, when the major construction benefits, if there are any, won’t happen for years?

It seems like government spending on old solutions that don’t work well anymore has become almost the standard operating procedure. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA) have both been made chronically underfunded and paralyzed by partisan infighting in Congress, which has led to a series of national transportation funding extensions, rather than common-sense reforms. The refusal of either Texas or the federal government to raise the fuel tax for the past 20 years is sufficient evidence for how unworkable and out-of-touch our current policies really are.

Trying to promote an expensive policy that is known in advance not to work is bad enough, but proceeding to do that while having no idea of where to get most of the money requires real chutzpah, a shameless audacity. If any Texas state agency has the history, credentials, and political clout to try make that work anyhow, it is TxDOT. To understand why, we need to take a more detailed look at TxDOT and the history of Texas transportation politics.

Texas road politics

Let us start with trying to understand how daily Austin congestion on I-35 and MoPac (State Loop 1) ever got to the point that now a lot suburban drivers who get to work on these roads dread a nerve-jangling daily commute. The reality is that Austin’s peakhour congestion has gradually progressed from tolerable to notoriously bad for decades. Nothing unusual, but the sort of end result you should expect when you try to keep building roads to maintain unsustainable transportation and land-use trends for too long.

Governments by their nature try to encourage economic growth. In Texas, as with most Sunbelt cities, cars, trucks, and roads have all become essential components of urban growth. The Texas fuel tax money is comparable to TxDOT’s oxygen supply. This state and federal fuel tax revenue can fund roads, but not transit under Texas law. Transit is left largely on its own, obliged to rely mostly on local funds and a shrinking level of federal transit funds.

Given the current lack of state land-use regulation outside the city limits of Texas cities, there is the potential opportunity to shift to greater land-use regulation. As data from the Texas Comptroller’s Office shows, more than 86% of the total Texas population is now urban and has outgrown our rural heritage.

These major metropolitan areas, the glowing patches you see from a jet plane at night, function as coherent economies. Ideally these metro areas should be governed as such, without the burden of conflicting and overlapping layers of city and county government.

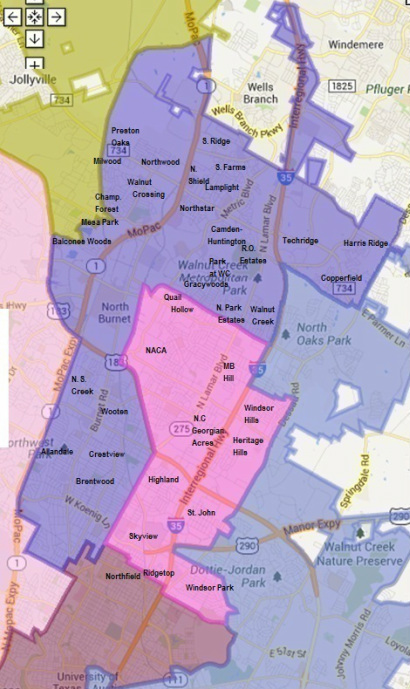

Austin’s regional congestion is aggravated by a combination of rapid regional population growth and unregulated suburban sprawl development. Over time, unregulated sprawl growth leads to decreasing urban mobility, increasing city-core land prices, and gentrification that drives out the city’s lower-paid service workers into suburban commutes, thus increasing traffic congestion even more. This has been particularly true for Austin’s African-American population, who for a variety of reasons have moved on to the suburbs, such as Pflugerville. (Source: Texas Tribune.)

As a University of Texas study observed “All told, the combined effects of, concentrated segregation and concentrated, gentrification of Austin’s historic African-American district provide a partial, explanation for the rapid decline in African-American residents between 2000 and 2010.”

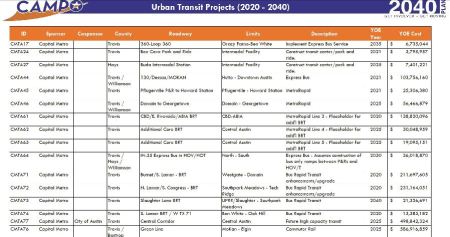

Official transportation and land-use policies have encouraged Austin-area sprawl development patterns. Photo: Mopacs, via Skyscraperpage.

Given these trends and the increasingly longer, more severe peakhour congestion periods in Austin today, a different approach beyond widening roads might be expected. But here in Texas, powerful political special interests continue to block meaningful transportation reform. TxDOT has great institutional power and this is still focused on providing roads to serve an exponential increase in cars and trucks. In the Austin area, TxDOT is supporting the CAMPO 2040 plan, which anticipates ever more roads, cars, and congestion — in other words, business as usual for as long as possible.

In 1974, when the first energy crisis hit the USA, Griffin Smith, Jr. wrote an excellent, well-researched account of how there came to be the Texas road lobby, the wide network of political allies devoted to building roads, and the effort to make roads and driving a permanent aspect of Texas lifestyle and culture. See «The Highway Establishment and How it Grew and Grew and Grew». So it was in Texas then, during the first energy crisis, and so it has been in Texas for the more than forty years since, without great change. Legendary Texas newspaper columnist Molly Ivins used to call TxDOT “the Pentagon of Texas” (see «Roger Baker: The Texas Road Lobby Meets Peak Oil»).

Over the years an established pattern of money and politics developed, whereby Texas governors as political favors appoint businessmen to be heads of state agencies. If a governor stays in office a long time, as Rick Perry did, he can (and he did) appoint all the Texas Transportation Commissioners (TTC, the five-person body that has the authority to decide when and where to build the state roads). With their overlapping six-year terms, TTC members even stay influential for a while after a governor leaves office.

It should come as no surprise, then, that highways and roads often tend to benefit the land developers, road contractors, and special interests who reward the governor and legislators with campaign contributions. According to Texans for Public Justice (TPJ), reviewing campaign contributions from 2003-2008, the special interests tied to the $175 billion Trans-Texas Corridor project “contributed $3.4 million to Texas candidates and political committees — a significant increase in their political activity.” You can see a comprehensive breakdown of those contributions at: http://info.tpj.org/watchyourassets/ttc/

Looming large in the background are federal housing and real estate policies that favor home ownership, especially detached single-family homes on individual lots, with generous tax write-offs and government-backed credit that largely favors suburban living. It’s an exploitative pattern of income redistribution from the city to the suburbs made possible by TxDOT’s publicly funded roads. (See «Starving the cities to feed the suburbs» in The Grist, 9 Jan. 2013.)

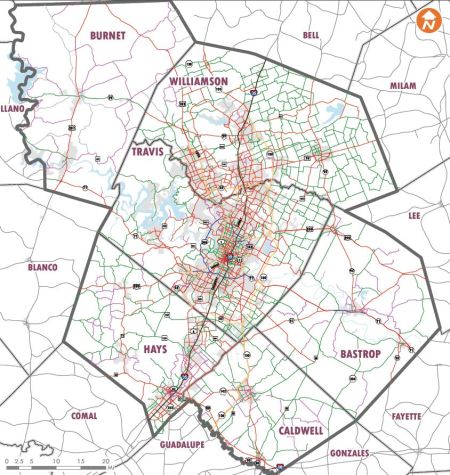

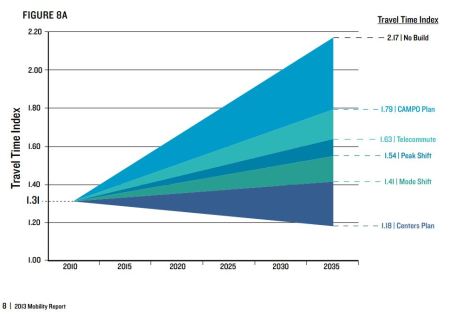

The CAMPO transportation planners who make the funding decisions for the Austin region are expected to ignore state, national, and global economic trends. Known resource limits like global warming, fuel costs, and water constraints are never considered in CAMPO’s growth and travel demand models.

Presently there is no transportation alternative — no “Plan B” — for the 2040 CAMPO plan, as there was in the region’s previous CAMPO 2035 five-year plan. The planners do not provide an alternative future that thinks longterm and which does not subsidize suburbs at city taxpayers’ expense. The 2040 CAMPO Plan states that even if our region finds the money (highly unlikely) to implement in the approved regional CAMPO 2040 Plan perfectly and in full, Austin-area congestion will keep getting worse until 2040.

Austin’s officially adopted longrange transportation plan aims at spending $35 billion dollars to maintain the current sprawl-based regional development trends, while doubling the population and putting 70% of this future growth, not just outside Austin, but well beyond Travis County. Absurd as the unaffordable nightmarish outcome might seem, it is the officially adopted plan. Lots of future sprawl is now Austin’s officially adopted future in both state and federal law, for regional transportation funding purposes.

As already noted, the biggest reason for this flagrant disregard of likely funding constraints and/or undesirable future outcomes is the special interests who profit in the short term from bad public policy. To give just one local example, as reported by the Austin Business Journal, Canadian land speculation investment group Walton Development owns about 15 square miles of raw land in the Austin area.

Walton Development and Management is preparing to make a big splash in Central Texas even though the company has had boots on the ground here since 2007. The Canadian-based land investor and master-planned community developer has seven communities in the pipeline in Central Texas, following years of researching the market and building relationships with consultants and government officials. Collectively, Walton owns 83,000 acres in Canada and the U.S. — and has quietly amassed about 10,000 acres in Central Texas…

The Calgary, Alberta-based company has been assessing numerous U.S. markets in the wake of the subprime mortgage meltdown and the Great Recession. Central Texas, predominantly south and east of Austin, has risen to the top of its hot list, as well as Washington, D.C.; Atlanta; Charlotte, N.C.; Orlando, Fla.; Dallas; Phoenix; Tucson, Ariz.; and Southern California.

TxDOT’s dedicated funding source — from motor fuel taxes and licensing fees for roads-only as specified by the Texas constitution — virtually guarantees an all-the-roads-as-fast-as-possible policy to address traffic increases. If I-35 is the state’s most congested corridor, the agency’s reflexive response is to spend whatever it takes to get whatever additional capacity is possible, the cost-benefit results notwithstanding.

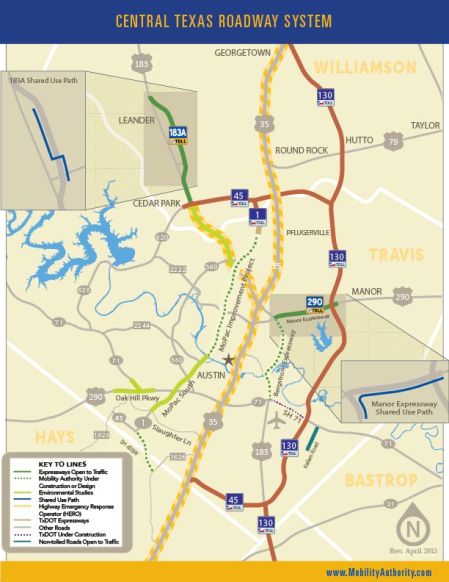

Recognizing I-35’s strategic regional importance against an increasing inability to cope with increasing population, local officials created what’s called the “Mobility35” (My35) partnership in 2011. Several studies, hundreds of public meetings, and $12 million later, courtesy of Austin taxpayers, what has emerged is a call for billions from local governments to fix the problem TxDOT’s way.

TxDOT is really broke and its credit lines look shaky

These are not business-as-usual times. The politics (and government funding) in support of cars and roads is so firmly entrenched and TxDOT is so politically powerful that its major threat is its money running out. TxDOT’s funding shortfalls have been growing and it probably now regrets ever having gotten into the unprofitable toll road business. That is why TxDOT invented Regional Mobility Authorities (RMAs) like the Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority (CTRMA) — to try to shift the road-funding burden onto the private sector with toll road municipal bond debt. (See Roger Baker’s article «Risky business in Central Texas: The toll road bond gamble».)

There can be little doubt that TxDOT has a serious solvency challenge (see «Roger Baker: Can TxDOT Avoid Financial Disaster? / 2»). We see a state agency that has to spend a big part of its total yearly income just to pay interest on its massive accumulation of road debt. (Source: http://www.collierfortexas.com/2015/02/25/txdot-addicted-debt/.)

The Texas Department of Transportation just issued its audited financial statements for 2014. They’ve rung up a debt balance of $19 billion. It was only $4 billion back in 2006. That’s when Rick Perry went on his debt binge. Of the $7.3 billion tax revenues TxDOT will take from Texans in 2016-2017, more than $2.4 billion will go to making debt payments.

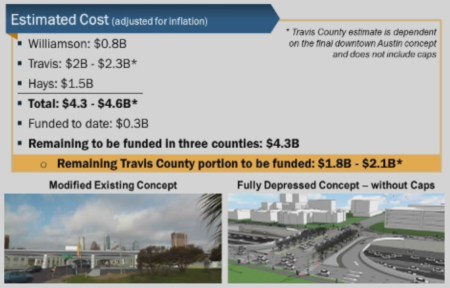

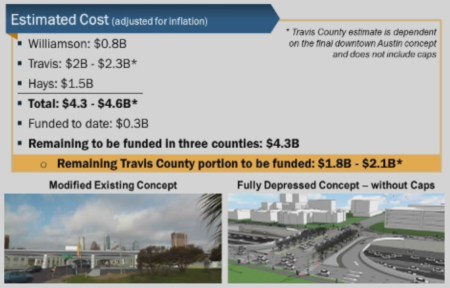

TxDOT is far short of sufficient funds to widen I-35 with its own resources, having identified only $300 million in-house out of $4.5 billion needed. That leaves TxDOT $4.2 billion short — over 90% deficient. In fact, the Travis County section of TxDOT’s My35 redesign is still $1.8 to $2.1 billion short, which should raise red flags for local property owners who could well be targeted for big tax increases.

When deciding what to do about I-35, should Austin taxpayers subsidize a highly politicized state agency, TxDOT, which has been steadily sinking relentlessly farther and farther into debt? TxDOT’S debt is now so bad that it has helper agencies, the RMAs (such as the Austin area’s local CTRMA), that can borrow even more to build privatized toll roads, supposedly shifting debt to the private sector; but when these efforts fail, the taxpayers will have to bail them out. Banks are not the only institutions “too big to fail”.

A rush-job November 2016 transportation bond election to widen I-35?

Some local officials already appear to be supporting TxDOT’s plans to widen I-35 in the name of relieving congestion. Austin’s influential state senator, Kirk Watson, has publicly registered his approval for TXDOT’S I-35 plans and seems to believe that it is possible for TxDOT to relieve I-35 congestion by widening the road. A Jan 28th Community Impact article titled «TxDOT targets I-35 in Austin for $158.6 million in congestion relief funding … State’s most congested roadways to get $1.3 billion» reports:

“Relieving traffic congestion is essential for our economy and our quality of life,” state Sen. Kirk Watson, D-Austin, said in a news release. “I’m pleased this initiative has put the emphasis on I-35, which is the most pressing congestion problem for Central Texas as well as the state. We’ve worked hard and successfully to develop a plan for reducing congestion on I-35 and this investment is key to moving that plan forward.”

Austin Mayor Steve Adler has been a vocal proponent of a November 2016 bond election for transportation. Adler has been talking about the need for a November 2016 transportation bond election, instead of waiting until the next bond cycle in 2018. As reported in the Austin American-Statesman, here is what Mayor Adler has said about the justification for a November bond election tied to I-35:

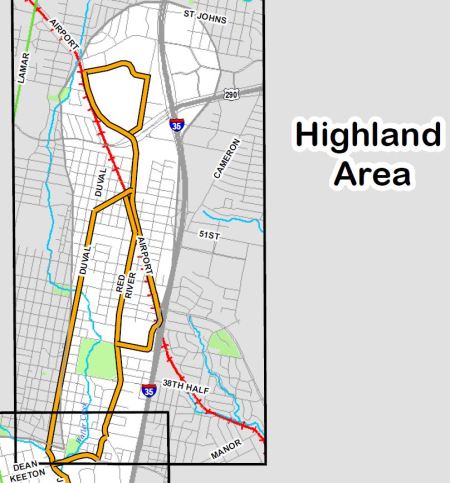

We need to do some significant movement with respect to mobility and transportation in 2016… It wouldn’t surprise me if we weren’t coming to the voters in November with some capital expenditures associated with transportation. We know there have been some proposals with respect to I-35 that include increasing capacity that include putting in managed lanes so that we can have buses traveling at 45 miles per hour regardless of traffic so as to encourage people to get out of their cars, and depressing lanes so that (there is) a visual connection of the east and west sides of I-35. And I think there might be an opportunity to do something regionally in that respect. Why not try for that? There are also road corridors in the city that have gone through corridor studies… Lamar, Airport Boulevard, MLK, I think. People are looking for some movement on (Loop) 360 and other roads that are in the southwest and northwest. I would think that we need to take a really hard look at doing those things.

In another Statesman article, Austin’s Assistant City Manager Robert Goode explains why speeding up a bond election for next November would be difficult at best:

Goode said there could be an “accelerated path” of 10 to 12 months, with the first two phases tightened up. But, remember, there are only nine months left until November 8, and phase one hasn’t even begun. So Goode, cognizant that Mayor Steve Adler (with the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce nudging in the background) has been pushing to do something in November, offered one more timeline: the “aggressive path.”

In other words, getting to a November 2016 bond election would mean serious compression of Austin’s existing standard bond review process in the name of addressing traffic congestion, without a sufficient vetting of what voter-approved debt would accomplish or how much would be needed — a political pig-in-a-poke labeled “Trust us!” that commits the city to a course of action that only TxDOT controls.

Maybe Austin planners and public officials should first find out in advance how much of the $4.5 billion TxDOT is willing and able to fund, and why TxDOT doesn’t fully pay for its roads like it used to do. Committing local funds to a “borrow and spend” agency billions in debt for a project with little positive outcome at some indefinite time in the future — bus lanes in ten years, at best; a depressed freeway covered with great streets; completion date and local costs, unknown and unknowable — ought to be setting off alarm bells, especially when TxDOT and Austin city management folks talk about “partnerships” and “partners”.

Public works projects, in particular big highway projects, have a history of long delays and large cost overruns. Boston’s 3.5-mile “Big Dig“, a tunnel under Beantown to eliminate the old elevated freeway through the city core, is a cautionary tale with similarities and problems we should expect here in Austin.

Scheduled to be finished in seven years at a cost of $2.8 billion, the Big Dig took sixteen years to complete and cost $14.6 billion; when adjusted for inflation — a 190% cost overrun, not including the $7 billion in interest required to pay off the debt incurred. As the Boston Globe headlined in 2008, a year after the project was completed, “Big Dig’s red ink engulfs state.”

Boston’s “Big Dig” under construction past city’s CBD. Project re-routed I-93 Central Artery into a central-city tunnel. Photo: Imaginerpe.com.

With TxDOT is already engulfed in debt, the I-35 My35 “partnership” should be seen as a plan to similarly engulf and encumber Austin’s taxpayers, thereby subordinating city finances to a condition of impotency to do little else but pay down debt on a state project that has little or no positive outcomes or predictable future except for the contractors and planners employed to pursue it.

Some of the details of this scheme were revealed in a Feb. 3rd TxDOT presentation to the Austin City Council’s Mobility Committee, chaired by Councilmember Ann Kitchen. The presentation can be viewed online in the video of the meeting, available from the City of Austin’s video archive, in the segment labelled “Items 7 & 8”.

About 23 minutes into the “Items 7 & 8” segment, TxDOT’s new District 14 Engineer, Terry McCoy, explains to the Austin City Council Mobility Committee what’s planned for I-35. Along with a lot of talk about “partnership” with the city, TxDOT, McCoy says, plans to spend about $4.3-4.6 billion on I-35 between San Marcos and Georgetown upgrading the “most congested corridor” in Texas. Around 35 minutes into the video clip there is a series of slides on parts of the project expected to start between 2016 and 2019, assuming that funding can be found.

TxDOT slide showing projected cost of proposed I-35 upgrade project. Graphic: ARN screen capture of TxDOT slide.

TxDOT’s message to Austin here is clear. In the partnership assumed by TxDOT’s McCoy and Austin’s Assistant City Manager Goode, TxDOT is the senior partner who makes the rules and if Austin wants anything beyond TxDOT’s basic least expensive, most lanes-for-the-bucks design, such as a “cut and cap” proposal to bury I-35 downtown, it’s going to cost local taxpayers a lot of money. As the Austin Business Journal has reported,

…One goal of the effort is to improve east-west connectivity across the thoroughfare in the urban core. The possibilities include intersection and access redesigns and adding bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure to cross the highway. “We’re adopting an ‘everything and the kitchen sink’ approach to I-35,” McCoy said. That includes either modifying the downtown section of I-35 along its current double-decker form or depressing all of the lanes, which would drop them below ground level. If city leaders and state transportation officials agree to lowering I-35, McCoy noted local funds could be used to then cover it up and put the new real estate to use in some way.

“Once you depress the main lanes of I-35, then you have the potential to build caps. What you do with those cap sections is up to the locals,” he said. “But from TxDot’s perspective…it is an amenity, so it would be a local cost item to pick up. TxDOT is essentially saying we cannot participate in the cost of constructing those caps.”…

(More information is disclosed in the Q & A session, about 40 minutes into that video segment.)

According to Assistant City Manager Goode, speaking in the same clip, Austin is behind about $4.5 billion in needed funds for its own City of Austin transportation needs over the next 30 years, a billion of that just for sidewalks.

A grassroots architect and planning coalition, ReconnectAustin.com, has been promoting a depressed I-35 design developed by UT Austin architect Sinclair Black. They have been trying for years to get TxDOT support for a sunken, capped, and covered-over I-35 along the east edge of downtown Austin. However, this is a concept that conflicts with TxDOT’s traditional design standards. (See, for example, «Reconnect Austin: Part Two … It’s a beautiful vision, but could it work?» Austin Chronicle, 31 Jan. 2014.)

Rendition of Reconnect Austin’s proposed “fully depressed” alternative design for I-35. Graphic: KUT Radio.

Pro forma, TxDOT defines I-35 improvements as squeezing the most possible cars onto its failing roads at the lowest cost. Economies of scale dictate elevated lanes on I-35 through downtown, and adding them onto MoPac South across the river. These are least-expensive road designs that ignore community plans and desires for connections, city space, and economic revitalization as well as returns from improved transportation infrastructure — goals that TxDOT simply doesn’t share.

TxDOT’s plans to add elevated lanes on MoPac South are proceeding despite organized resistance from environmentalist groups like the Save our Springs Association. How to distribute increased amounts of inbound commuter traffic into downtown is still unresolved, but that’s the city’s problem, not TxDOT’s.

It will take TxDOT another two years to complete the NEPA federal study process on the downtown section of I-35. Depressing I-35 through downtown as opposed to TxDOT’s standard design would cost about $300 million extra, and capping it over at least as much, but the cap is a feature TxDOT won’t pay for. Toll lanes with express lanes for buses on I-35 that Mayor Adler mentions could not be implemented for perhaps a decade, and that depends on another billion or so in public money which isn’t there now.

If ever there was a time to stop and look at alternatives to expanding I-35, that time is now, before we commit scarce local money for vague allusions to an urban-friendly freeway design unlikely to be delivered and toll-lane-only congestion relief, which TTI calls a “limited option.”

November bonds to widen I-35 will be a hard sell once it’s widely known that real congestion relief is not possible for any price, especially when a decade or more of detours and disruption — and yes, even more congestion — will be required to fix the unfixable. The bottom line is that I-35 cannot be decongested in any meaningful sense, not with Mucinex or for any amount of money. That even when completed, I-35 cannot be made into a less frustrating driving experience than it is today and that is what the A&M’s TTI has been saying.

Austin could choose its own future, as Houston is trying to do

On January 28, 2016 Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner told The Texas Transportation Commission — the body that governs TxDOT — that he wants a paradigm shift in transportation planning that makes better sense for cities. Given Turner’s long record of leadership in the Texas House of Representatives and now, as Houston Mayor, we can only hope that other Texas big city mayors take note and follow suit. (Source: Streetsblog.org.)

Here is some of what Sylvester Turner said:

…We’re seeing clear evidence that the transportation strategies that the Houston region has looked to in the past are increasingly inadequate to sustain regional growth… The region’s primary transportation strategy in the past has been to add roadway capacity. While the region has increasingly offered greater options for multiple occupant vehicles and other transportation modes, much of the added capacity has been for single occupant vehicles as well… It’s easy to understand why. TxDOT has noted that 97% of the Texans currently drive a single occupancy vehicle for their daily trips. One could conclude that our agencies should therefore focus their resources to support these kinds of trips. However, this approach is actually exacerbating our congestion problems. We need a paradigm shift in order to achieve the kind of mobility outcomes we desire…

Turner went on to make three recommendations:

…We need a paradigm shift in how we prioritize mobility projects. Instead of enhancing service to the 97% of trips that are made by single occupant vehicles, TxDOT should prioritize projects that reduce that percentage below 97%. TxDOT should support urban areas by prioritizing projects that increase today’s 3% of non-SOV trips to 5%, 10%, 15% of trips and beyond. Experience shows that focusing on serving the 97% will exacerbate and prolong the congestion problems that urban areas experience. We need greater focus on intercity rail, regional rail, High Occupancy Vehicle facilities, Park and Rides, Transit Centers, and robust local transit. As we grow and densify, these modes are the future foundation of a successful urban mobility system. It’s all about providing transportation choices.

Imagine Austin, where some brave politician stands up and speaks up like Houston Mayor Turner did, and declares independence from TxDOT’s highway idolatry — the simplistic view that somehow, someway we can build roads faster than Detroit et al. can build cars. Surely not all of our leaders believe that widening I-35 should be our top transportation priority for our limited resources — perhaps a billion dollars in AAA bonding capacity to bankroll a bankrupt state highway department. My35 alone could consume everything we could put up and more; but, in all fairness, we could easily use up all of our debt capacity widening non-state roads inside Austin, and that would also discourage alternatives and make congestion worse, too.

Whatever we decide about funding I-35 — beyond the $12 million we’ve already spent for planning — will say a lot about where we intend to go as a city. Any additional local money for the My35 project is a slippery slope, a probable Point of No Return. After all, “in for a penny, in for a pound”. Eventually, at some unknown time in the future, after years of construction disruption, the freeway would carry more vehicles, but congestion overall would be worse, not better. Transit, bike, and pedestrian benefits promised in the project are longterm and incidental, and could better be achieved through direct spending elsewhere.

Healthy cities need integrated transportation and land-use planning, the latter unrecognized and unacknowledged in TxDOT’s institutional mindset. Cost-effective, efficient transportation is the direct result of integrated transportation and land-use planning from the outset, using tools like Smart Growth and transit-oriented development (TOD) to maximize mobility at an affordable cost. Cities are almost by definition congested, but urban mobility goes beyond movement, and is heavily dependent upon destination proximity and modal choice.

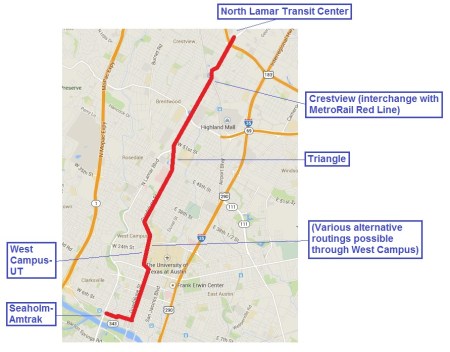

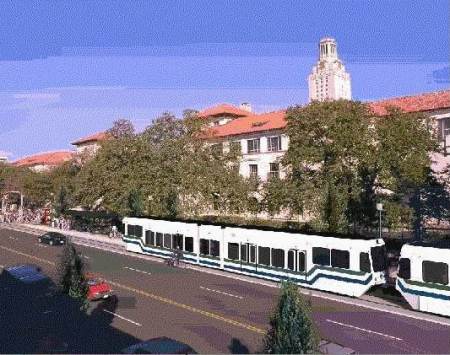

Inside the city of Austin alone, there are billions of dollars in existing, but neglected, road, bike, and sidewalk needs. But for a real game changer, Austin needs a Guadalupe-North Lamar light rail line from downtown to some point past the North Lamar Transit Center.

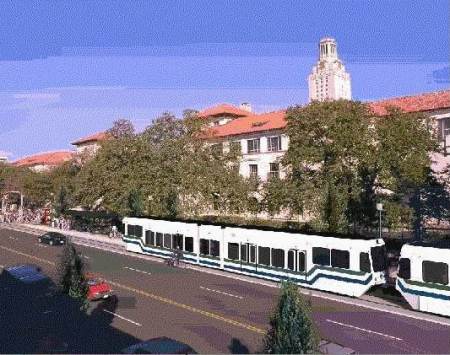

Rendition of LRT train on Guadalupe (the Drag) passing UT campus. Graphic: Capital Metro, via Light Rail Now.

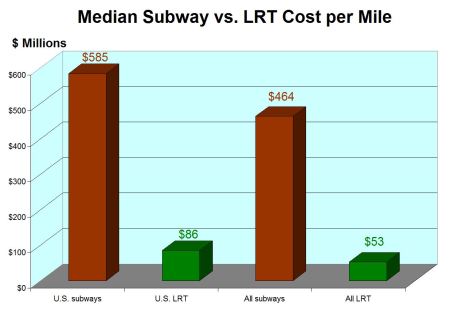

Running in-between and parallel to our two most congested roads, I-35 and MoPac, these trains would reinforce and complement the transit-friendly land uses that have existed in this corridor since the days streetcars plied these same streets. (See «Austin’s First Electric Streetcar Era».) Urban rail in reserved lanes on the street would deliver 40,000 riders a day to and from the city core, while experience elsewhere says that this small beginning would generate billions of dollars’ worth of new tax base for an investment of less than $750 million, half of which would likely come from the Federal Transit Administration.

Compared to rebuilding I-35 from Georgetown to San Marcos, a Guadalupe-North Lamar light rail project is a relatively simple transportation endeavor. It is a project we’d build, we’d own, we’d control, we would pay for with identified funds, and would benefit from directly — compatible with buses, biking, and walking. Plus, it would be built on a relatively predictable schedule of less than five years with an extremely high potential for payback within a decade of opening, while setting the stage for better-funded, more frequent, and more comprehensive public transit throughout the city and the region.

If 2016 is Austin’s year of mobility bonds on November’s ballot, a Guadalupe-North Lamar light rail line should be the first priority. A plan for this could be quickly assembled from at least four official past rail studies done on this corridor since 1984 — the last, a full Preliminary Engineering/Draft Environmental Impact Statement from 2000. Furthermore, it could be accomplished using the well-known competent national consulting team, AECOM, already hired by Capital Metro to essentially study the same corridor.

What’s needed now is political leadership to get it done. With our backs literally up against TxDOT’s wall of debt for an insanely risky My35 rebuild, the facts speak for themselves.

Rail References

Ridership

• Light Rail Corridor. Austin, Texas (November 2000) — Federal Transit Administration New Starts summary

https://keepaustinwonky.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/fta-new-starts_small-starts-austin-texas_light-rail-corridors.pdf

Billions in new tax base

The two best examples of initial light rail lines with similar characteristics, i.e., Big Dot connections and high ridership, are Houston and Phoenix.

• Houston METRO — $324 million to construct, opened 2004

$8 billion in economic development on initial 7.5 mile Main Street line since 2004

http://www.planetizen.com/node/81699/texas-cities-see-mass-transit-path-economicdevelopment

• Phoenix METRO — $1.351 million to construct, opened 2008

$8.2 billion in economic development on 19.6 miles Phoenix to Tempe since 2008

http://www.bizjournals.com/phoenix/news/2015/07/28/valley-metro-development-alonglightrail-tops-8.html

Other examples with more mature systems

• Dallas DART — 157% ROI, 85 miles, 61 stations

https://www.dart.org/about/economicimpact.asp

• Portland MAX (TriMet) — $4.66 billion (adjusted to 2015 $) to construct 59.7 miles of light rail with 97 stations, yielding ROI of $11.5 billion of economic development within walking distance of stations since 1986.

http://trimet.org/business/

• Salt Lake City TRAX and FrontRunner — $3.6 billion to construct 45 miles light rail and 88 miles of regional (commuter) rail, yielding ROI of $7 Billion economic development since 1999.

http://www.sltrib.com/csp/mediapool/sites/sltrib/pages/printfriendly.csp?id=2665260

■