Plan now for conversion/inclusion of NW corridor, Red & Green Lines in CapMetro’s new light rail system

7 November 2021

By Lyndon Henry

Lyndon Henry, an urban and transportation planner, is a technical consultant to the Light Rail Now Project of Texas Association for Public Transportation and contributing editor to Austin Rail Now (ARN).

Capital Metro, Project Connect, and the Austin Transit Partnership seem to be heading toward a serious and expensive mistake, ultimately with longterm adverse consequences: setting in concrete and steel the exclusion of the metro area’s northwest corridor and Red Line from Austin’s new electric light rail transit (LRT) system. It’s a decision currently in planning and at “only” 15% of design, but the eventual results could include suppressing potential ridership, raising ongoing operating costs significantly, and locking in place a two-tier rail transit operation of two different technologies requiring separate but duplicative facilities to serve similar segments of the metro population.

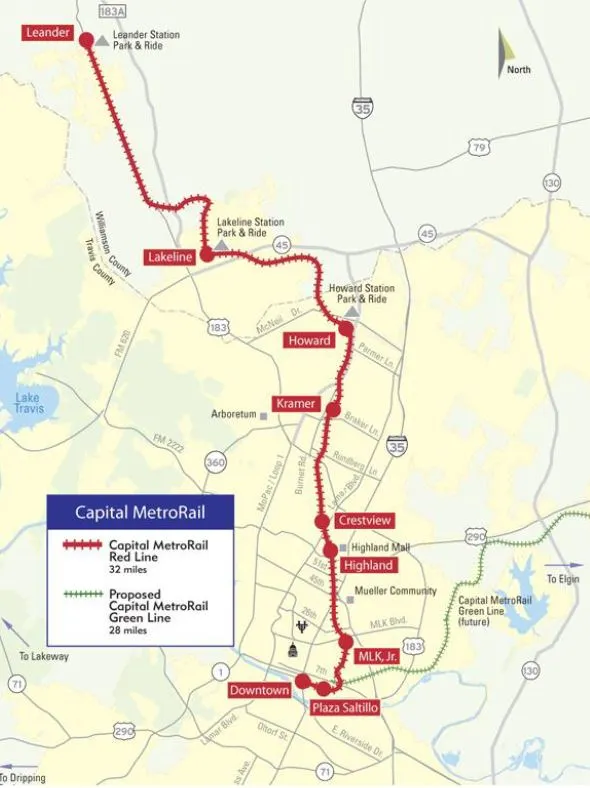

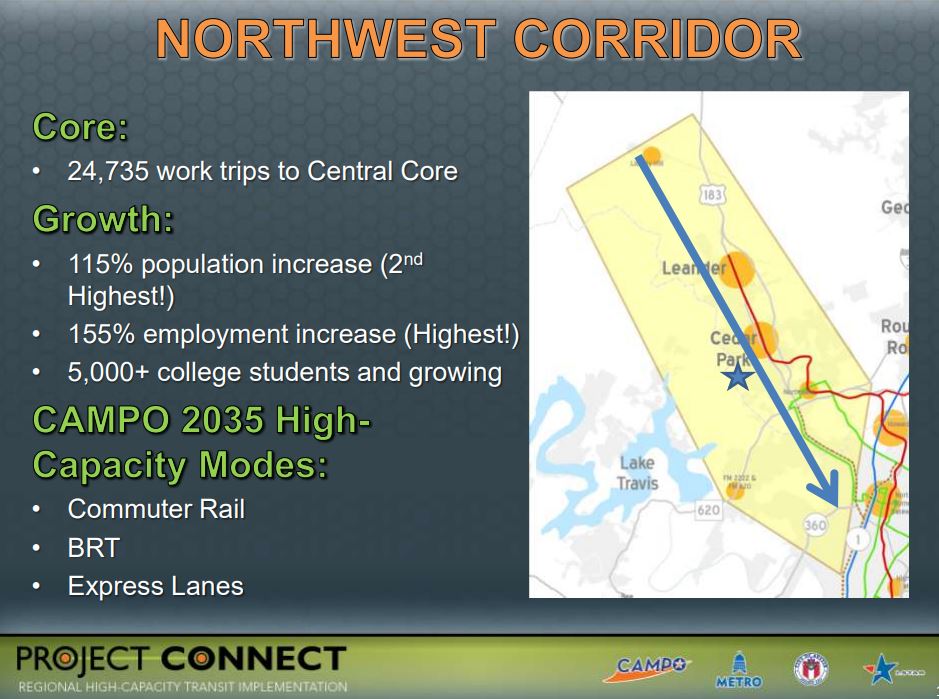

The northwest corridor – generally centered along the US 183 highway and 183A tollway, and also served by the Red Line “commuter rail” transit service to Leander – comprises metro Austin’s second-heaviest growth and travel corridor, after I-35. With density averaging more than 6100 persons per square mile, this corridor includes the City of Austin’s rapidly densifying northwestern suburban neighborhoods as well as the fast-growing suburban cities of Cedar Park and Leander. A member of Capital Metro’s service area since the agency’s inception, in 2020 Leander was described as an “Austin area suburb named as fastest growing city in America”. [Austin Business Journal, 26 July 2020]

“Urban commuter rail” substituted for light rail

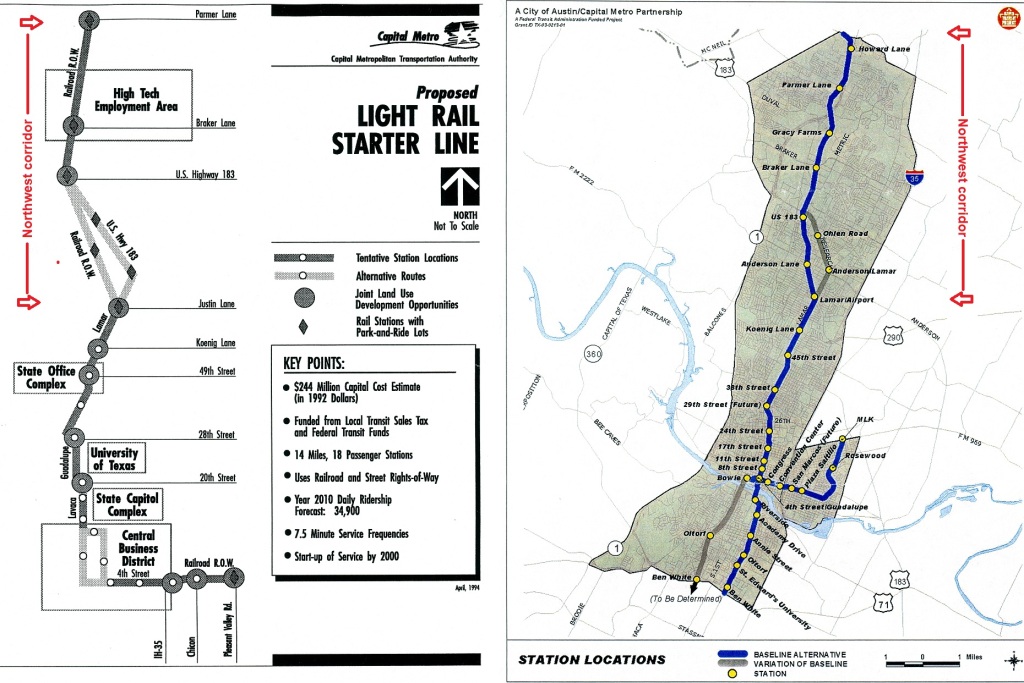

From the 1970s, the railway line to Leander was envisioned as a crucial branch of a future LRT system, and as such was included in Capital Metro’s official light plans in the 1990s and early 2000s. However, to install a rail transit operation quickly, the MetroRail DMU (diesel multiple-unit) service, characterized as “urban commuter rail”, was conceived as an interim replacement, and approved by voters as part of the All Systems Go program in 2004.

At that time, the diesel-powered, bare-bones, lower-capacity, mostly single-track approach seemed an affordable, lower-risk way to get a minimalist rail transit operation up and running – in effect, a “demonstration line” allowing the metro Austin public to experience rail transit in their community, and to enable transit planners to assess community response. Unfortunately, current plans appear to perceive the “urban commuter rail” system – both the operating Red Line and new Green Line – as a permanently separate system, distinct from the electric LRT system now being implemented in central-city Austin.

Advantages of LRT for northwest corridor

Why is this such an unfortunate policy? Mainly because “commuter” rail (regional passenger rail) is a far less efficient and cost-effective mode than electric LRT for this kind of rapidly developing and densifying urban-suburban corridor. Here are some of LRT’s strongest advantages for Austin’s northwest corridor:

►Faster, more frequent service — LRT’s high-power electric rolling stock, with higher acceleration/deceleration rates, would be able to provide faster, much more frequent service and thus substantially higher capacity for journeys within this major travel corridor to and from Austin’s central area.

►Seamless connections — By interlining with the Orange and Blue LRT lines, LRT would offer a convenient, comfortable, “seamless” journey – without the need for a transfer – to northwest corridor passengers traveling to and from major destinations such as the University of Texas West Campus area, the Capitol Complex, the heart of downtown, and the ABIA aiport.

►Significantly higher ridership — Faster, seamlessly direct rail transit service between the northwest corridor, the major activity centers within Austin’s core, and ABIA should itself stimulate a significant increase in ridership. The higher performance features of LRT could make additional stations in the corridor more feasible, adding a further boost in ridership.

►Enhanced TOD potential — The availability of a fast, seamless, direct rail connection to Austin’s core and ABIA can be expected to further enhance the attraction of northwest corridor station sites for transit-oriented development (TOD). This in turn would likely create its own additional stimulus to ridership.

►Lower operating costs — On average, the operating & maintenance (O&M) costs of LRT per passenger-mile (p-m) amount to just 34% of those of DMU “light commuter” operations of the same type as Capital Metro’s MetroRail. Put another way, MetroRail DMU operation costs about 3X as much per p-m as LRT. To take some examples from the most recent National Transit Database report (2019) by the Federal Transit Administration, Capital Metro’s Red Line service costs $1.73 per p-m compared to $0.85 for Dallas’s DART LRT system, $0.80 for Portland’s MAX, $0.39 for San Diego’s Trolley.

►Elimination of duplicative service — Current planning seems to envision two permanently separate transit systems/technologies, with duplicate rolling-stock fleets, service facilities, etc., to serve corridors with basically very similar demographics within the same urbanized area. This seems inherently wasteful and unnecessary. Unifying these separate operations could further reduce costs by both eliminating duplication and facilitating economies of scale in procurements.

►More flexible alignment opportunities — Unlike MetroRail’s “heavy” railroad rolling stock, LRT trains can turn street corners and run in city streets, as needed, compatibly with motor vehicle traffic. This would make possible, say, a simple crosstown rail transit connection between the Convention Center station and the Seaholm development area.

►Compatibility with freight rail — Capital Metro’s privately contracted freight rail operation is currently an important revenue source for the agency; in addition, by reducing motor truck traffic on metro area roadways, it provides a net environmental benefit. MetroRail passenger service currently shares these tracks with freight via temporal (time) separation (freight operations run late at night, leaving the tracks free for transit service from morning to evening). LRT could operate likewise. LRT operations elsewhere also provide models and precedents for this: the San Diego Trolley (since 1981) and Salt Lake City Trax (since 1999) have successfully and safely shared tracks with freight railroad services for decades.

Unifying MetroRail and LRT

A unified system, with electric LRT service out to Leander, would not only serve one of the heaviest-traffic and fastest-growth corridors in the city with a proper high-capacity rapid transit-type operation, but would also, as noted above, enable an uninterrupted one-seat ride from Leander and other points along the Red Line corridor straight to UT, the Capitol Complex, and the heart of downtown. Making this a northwest extension of the planned Blue Line LRT would also incorporate a direct connection to ABIA. The Red Line service, from Leander to ACC’s Highland campus, through East Austin, and into the lower east side of downtown, could also be maintained with LRT.

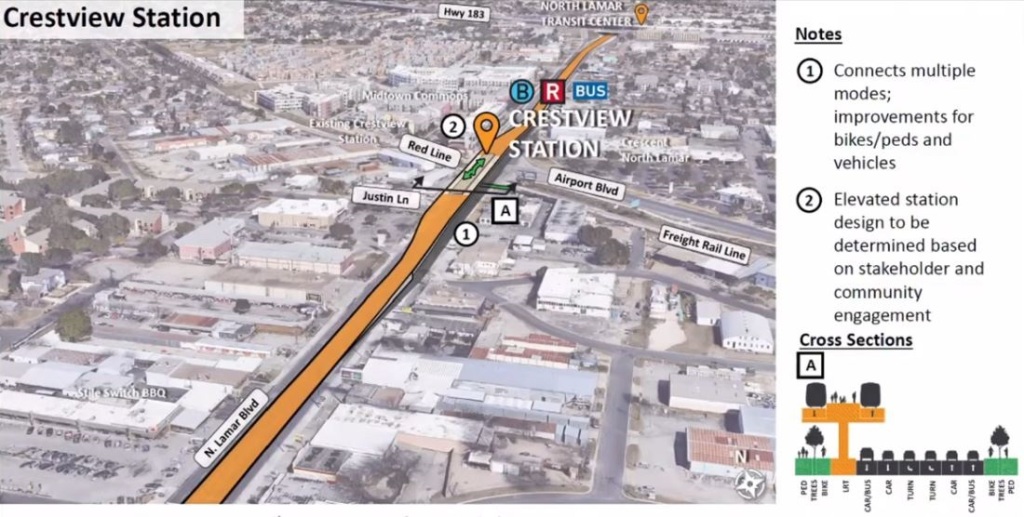

Converting the MetroRail Red Line to electric LRT, and incorporating a connection in the grade-separation already being planned at Crestview, would be a relatively moderate-cost project, much less than building a new line from scratch. On average, using and modifying an existing railway alignment provide by far the lowest-cost type of LRT line construction. Planning for an integrated LRT system including the northwest line to Leander would need planning for both design and funding.

In terms of design, two engineering features are necessary:

• Plans for the grade-separated interchange at Crestview (N. Lamar/Airport Blvd.) would need to be modified to include a future track junction to enable northwest-corridor trains to join and interline with the Orange/Blue Line tracks on North Lamar. As currently planned, both rail alignments would be separated from the North Lamar roadway lanes; but a total grade separation is also planned between the existing railway (Red Line, which would tunnel under the intersection), and Project Connect’s proposed LRT alignment (which would fly over the intersection on a viaduct). This would force a cumbersome transfer for all LRT passengers traveling to or from the northwest and points south. A track junction would facilitate interlining and enable the seamless, transfer-free ride described earlier.

• LRT system rail and vehicle wheel profiles that conform with railroad specifications would need to be designed and selected (i.e., the rails and car wheel profiles for the new LRT system would need to match those currently in use for the Red Line). This is standard for transit systems that include track-sharing with heavy railroad operation.

However, it must be realized that Project Connect’s planners are moving quickly toward finalizing a two-tier separated MetroRail and LRT dichotomy permanently in their final design, now 15% completed in late 2021 and expected to be 30% completed in the spring of 2022. Unless that design is tweaked to include the unification and compatibility measures described in this report, residents in the northwest corridor, including Leander, would likely never have that one-seat ride to UT, the Capitol, and ABIA, and Capital Metro’s rail transit services would be burdened with higher-than-necessary O&M costs.

The inclusion of the northwest corridor, and conversion of the Red Line to LRT, are not part of the large Project Connect transit program approved by voters in November 2020 and now underway. These plan changes would need to be approved, funded, and undertaken as a future separate project. This would include negotiating for and receiving a track-sharing waiver from the Federal Railroad Administration (as was done in San Diego and Salt Lake City). But surely the multiple benefits and substantial cost savings justify investing the effort and resources to achieve a unified regional LRT system for metro Austin. ■

Another unserving, unsustainable, unproductive, inefficient, way too costly proposal by LH, the perennially wrong pseudo-expert, who has no grasp of evidence proven ways to improve people mobility. Austin citizen Richard Shultz, who gets no $ for his research ahd proposals, has far better ideas on how to actually increase people mobility for all at much lower cost at http://www.cmt4austin.org/