Busy section of Austin’s Drag, Guadalupe St. at W. 24th St. Official city planning by CTR has proposed curbside transit lanes, with buses running on outside lanes as seen in this photo. (Screenshot from Google Streetview.)

♦

By Lyndon Henry

The following commentary has been adapted and expanded from remarks posted to an online Austin rail discussion. Lyndon Henry is a transportation planning consultant, a technical consultant to the Light Rail Now Project, an online columnist for Railway Age magazine, and a contributing editor to Austin Rail Now. He is also a member of the Light Rail Technical Forum and Streetcar Subcommittee of the American Public Transportation Association (APTA). His comments highlight the vision of Austin Rail Now and other transit advocates that light rail is justified in, and needs to be planned for, a number of the Austin area’s major travel corridors.

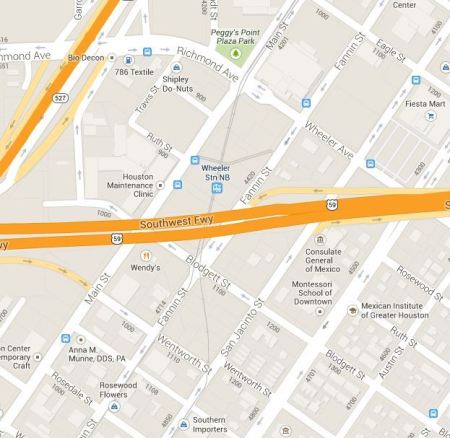

As most Austinites are undoubtedly aware, the Drag is that section of Guadalupe St. stretching between (approximately) West MLK Jr. Blvd. and W. 27th St. Straddled by the University of Texas campus on its east side and the high-density West Campus neighborhood on its west side, the Drag is perhaps the single most important segment of the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. See: «Long saga of Guadalupe-Lamar light rail planning told in maps» and «Dobbs: Density, travel corridor density, and implications for Guadalupe-Lamar urban rail».

Map shows the Drag area (Guadalupe St., running north-south in center). UT campus lies on the east, West Campus neighborhood on the west. (Screenshot from Google Maps.)

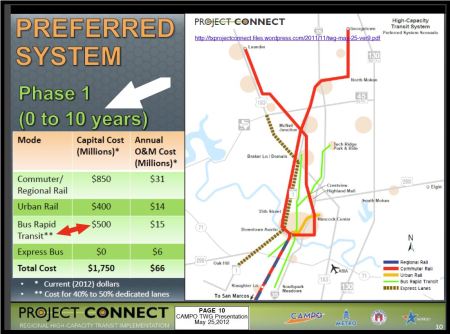

Now, driven partly by their fixation to substitute buses for rail as “rapid transit”, and partly by pressure from some community groups and activists, local civic leaders and official planners are floating plans for dedicated transit (read “bus”) lanes on the Drag. (Official planning defines “the Drag” as continuing north to W. 29th St.)

Last month (August 2015), AURA (originally Austinites for Urban Rail Action), a grouping of mostly Millennial-aged urban planning enthusiasts, posted a proposal for major improvements on the Drag, one of which suggested: “Extend transit priority lanes from Downtown to the Drag”.

At peak periods, transit moves roughly half of the people passing through the corridor. This is to be expected in a central location like the Drag, as transit is by far the most efficient way to move people in a city.

Given the anticipated growth of the city, increasing the throughput of people in the corridor is of paramount importance. The city should plan ahead for increased frequency of existing bus routes, and continue to examine the viability of Guadalupe as a future corridor for rail service. Buses should not have their effectiveness limited by less efficient forms of mobility. Two lanes of Guadalupe should be dedicated solely to transit.

Back in May, per its contract with the City of Austin (COA), UT’s Center for Transportation Research (CTR) produced for city staff a memo of its findings with respect to installing dedicated lanes on the Drag. As summarized by AURA’s John Laycock, the report “modeled three scenarios: Scenario 0) the baseline scenario, Scenario 1) a transit lane in each direction on Guadalupe, and Scenario 2) diverting the buses completely off of Guadalupe onto San Antonio.” Laycock reports that the city subsequently requested CTR to model an additional case, involving one transit lane northbound on Guadalupe and another southbound on Nueces/San Antonio. Results from that additional modeling effort apparently have not yet been released publicly.

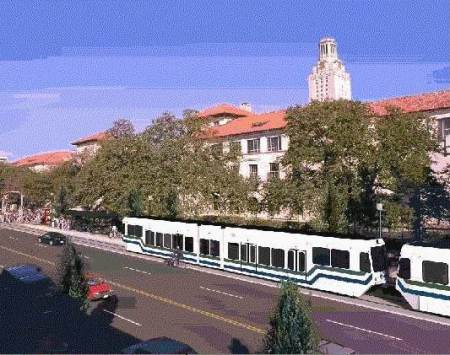

The proposal for dedicated transit lanes on the Drag may seem fairly benign, helpful to public transport and innocuous to the prospects for light rail (LRT). However, installing reserved transit lanes without broader planning for rail can raise some quite serious problems. Depending on their design and implementation, transit lanes could significantly improve or seriously impede the prospects for light rail transit (LRT) — by far, the most feasible and affordable rail option — in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. (See «Plan for galvanizing Austin’s public transport development: Light rail starter line in Guadalupe-Lamar».)

First, I’ll note that implementing a high-quality bus service as a precursor to rail can be an effective way of building ridership and preparing the public for the coming rail upgrade. Likewise, establishing reserved transit lanes that can be dedicated to rail can also be helpful. However, both infrastructure and configuration of dedicated transit lanes, done improperly, can create problems.

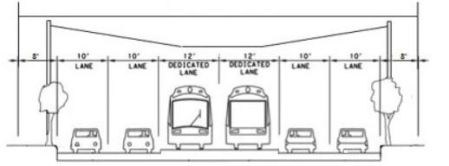

• Infrastructure — Proponents of dedicated transit lanes have argued that all that’s needed is to paint some stripes on the street. And certainly, in the scheme of transit capital projects, just “painting” markings on pavement is relatively cheap. But there’s almost always more involved. The Guadalupe-Lavaca transit lanes, for example, included repaving, plus bus stop relocation and upgrading. Parking meters were removed. And the project has resulted in effectively eliminating the possibility of dedicated LRT tracks on those sides of these streets (bus traffic too heavy).

Buses use curbside reserved lanes on one-way Lavaca St. downtown. Curbside lanes on the Drag would be similar, but on two-way street. Photo: L. Henry.

In previous discussions I’ve suggested that LRT dedicated lanes would need to be relocated on the opposite side of each street. Total cost of the downtown bus lane project was about $370,000 — not a billion-dollar investment, but enough of an investment certainly to give pause to totally redoing this project, or making substantial modifications to it (although modification to add LRT would definitely be a highly worthwhile investment).

We also don’t know what COA and Capital Metro have in mind for the Drag project. Some community transit activists might be thinking very minimalist, but what are official planners thinking?

• Configuration — The precise alignment on the transit lanes also needs serious consideration with respect to the needs of LRT (and evidence suggests that a substantial portion of the Austin community would like to see LRT as a project on the planning table now). Curbside lanes — as assumed in the CTR design, described above — are used by several major LRT systems (Portland, Houston, Dallas, and Denver come immediately to mind), but this configuration can often encounter serious problems, mainly with motor vehicle right-turns and especially pedestrian traffic (including where the right turns are made). Another problem for the Drag is the number of driveway cuts and the issue of access to businesses along this commercial alignment.

Denver: Passengers waiting to board LRT train running in curbside lane on Stout St. Photo: Peter Ehrlich.

To be sure, a number of different LRT alignment and configuration options are possible. My preferred alignment concept for the Drag has been to keep both LRT tracks on Guadalupe, in the center (with stations also in the center), and the outside (curb) lanes continued for mixed motor vehicle traffic, including buses. The main reason for this configuration is that buses need access to right-side loading at stops, and I envisioned that local routes like #1 would need to be continued. Of course, bus routes could be moved further west, probably to San Antonio-Nueces, but keeping them on Guadalupe would facilitate relatively easy transfers to and from LRT and bus.

Ideally, the main Drag segment in this heavy-pedestrian/heavy-transit traffic area should be converted to a pedestrian-transit mall, with general motor vehicle traffic prohibited (except perhaps in the case of service vehicles for adjacent businesses). However, a design with reserved transit lanes plus a single mixed-traffic lane in each direction would appear to be possible.

To sum up: While dedicated transit lanes, with very minimal investment, could possibly be helpful as a preparation for LRT, I’d recommend huge caution and vigilance as this notion moves forward. Keeping particularly in mind the considerations I’ve raised above.

In this regard, it’s important to realize that a major chunk of Austin’s civic leadership, and planning establishment, still regard MetroRapid as the city’s “rapid transit system”. Likewise, the fantasy persists that Austin could “become the best bus system we can be” without a rail system. (Cities with the “best bus systems” also seem to happen to have excellent rail systems too.) Reserved transit lanes on the Drag could advance the case for LRT, but only if they’re properly configured, designed, and planned in the context of an ultimate LRT outcome. ■