Austin: To subway, or not to subway?

29 February 2020♦

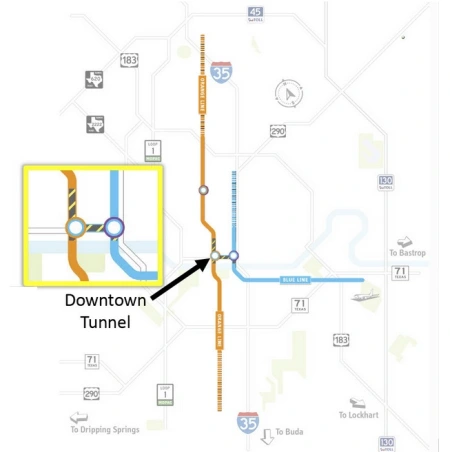

As ARN reported in our posting of 31 January, Project Connect Connect (Capital Metro’s major transit investment planning program) together with most of Austin’s top civic leadership apparently are now focusing on a massive multi-modal transit development vision with light rail transit (LRT) as its centerpiece, running in both the the Orange Line (North Lamar-Guadalupe-South Congress) and Blue Line (downtown-East Riverside-ABIA) corridors.

As we also noted, ridership volumes projected for the Orange Line are eye-popping – certainly, unusually high levels for a single U.S. starter line in a mid-sized Southwest city. Projected 2040 weekday ridership (61,600 to 73,500) would exceed or rival ridership experienced by the original single lines of relatively new major LRT projects (e.g, Los Angeles, Denver, St. Louis, Dallas, Houston) and even rail rapid transit – “heavy rail” metro – projects (e.g., Philadelphia-Lindenwold, Miami, Baltimore).

These volumes appear to underlie suggestions by Project Connect planners that segments of the proposed LRT lines, particularly in Austin’s Core Area, merit consideration as subway alignments. In addition, a segment of the Blue Line, several blocks eastward, is also considered for subway; it would feed into the Orange Line via an underground junction at Republic Square.

Need for greater capacity

Heavy peak transit passenger flows typically require more frequent trains and longer consists (number of cars per train) to provide sufficient capacity. Especially in concentrated downtowns and other central-city locations, these factors can in turn impact traffic flows across intersections by not just cars and trucks but also pedestrians, cyclists, and transit buses.

Particularly fueling interest is a subway tunnel is the length of downtown blocks (about 300 feet), which would limit train lengths to no more than three coupled LRT cars. This implies the need for a subway alignment in the Core Area north of the Colorado River (known as Lady Bird Lake) and south of Martin Luther King (MLK) Blvd. (basically, the southern border of the University of Texas campus).

In addition to eliminating conflicts with surface traffic and providing adequate capacity well into the future, the case for a subway appears to be bolstered by political support, both among the city’s top civic leadership as well as the public at large.

Subway drawbacks

On the other hand, there are significant drawbacks to subway rather than surface LRT line construction, both generally and in Austin’s case:

• Subway construction typically is far more expensive than surface facilities, entailing a much heavier demand on financial resources. According to cost estimates from Project Connect, building a downtown subway for an Orange Line LRT, rather than installing a surface alignment, would add nearly $837 million to the project investment cost.

• Federal Transit Administration funding is limited, and FTA officials tend to prefer more modest investment grant applications so that available funding can be spread more broadly. Increasing the cost of a New Start project significantly may render a project less competitive and lower it in the queue of projects seeking funding. Adding a downtown subway segment to, say, a starter LRT line from the North Lamar Transit Center to downtown would increase total project cost by over 65%.

• Particularly because the precise details of what’s below the surface are largely hidden, subway construction is far more prone to unexpected challenges and costs which can result in hefty budget overruns.

• Operating & maintenance (O&M) costs for subway LRT operation tend to be somewhat higher than for surface operation because of the added operational costs (e.g., electrical power) and functional maintenance needs of ventilation systems, elevators, escalators, etc. Also, maintenance-of-way work (maintaining track, power supply, signals, etc.) tends to be more expensive in underground conditions.

• Compared to surface LRT, where trains are run in the open and stations are easy to see and recognize – orienting the public to the available service and helping attract potential passengers – subway operations and stations are almost entirely out of sight, except for small entrances to ground level that may be difficult for the general public (especially new riders, tourists, etc.) to find and recognize.

• Access-egress to-from subway stations, which require climbing stairs, waiting for and riding elevators, or riding escalators, can be somewhat daunting. (The access time penalty is often included in ridership forecast models.) While accessing surface LRT platforms often requires waiting for traffic or pedestrian signals, typically the time penalty and physical difficulty are much less.

Capacity of an Orange Line surface LRT line

While there’s no question that a subway would provide greater potential to accommodate ridership further into the future, a technical examination of the capacity requirements to meet Project Connect’s actual predicted peak ridership volumes in the 2040 target year suggests that these could be met by a surface LRT alignment (running in dedicated street lanes) through Austin’s downtown, even with the limitation of 3-car trains running at very narrow headways (i.e., high frequencies). For example, Both Dallas and Calgary (Alberta) operate 3-car trains providing heavy capacity through downtown street alignments. Dallas runs trains as close as 4-min peak headways; Calgary runs trains as close as 2.4-min peak headways. Presumably Austin could operate trains at least as close as 3-min headways, or 20 trains per hour.

Project Connect assumes each LRT car would have a peak capacity of 172 passengers. Thus a 3-car train would provide capacity for 516 passengers. Running 20 three-car trains per hour would provide peak capacity of 10,320 riders per peak hour/peak direction. Using the rule of thumb that peak ridership in the peak direction = 10% of daily weekday ridership, this implies that surface LRT trains would provide an operating capacity capable of handling ridership up to 103,000 a day.

Project Connect forecasts daily ridership of 61,600 for the 90% street-alignment option, and 73,600 for the 50% grade-separated option. Extrapolating from the agency’s estimates, ARN calculates the annual growth rate for Project Connect’s 90% street option to be 2.2% per annum. At that rate, it would take another 24 years to reach 103,000 daily ridership level, or the year 2064 – 44 years from today – when the capacity of street running with 3-car trains would presumably be reached.

While a surface LRT line may provide adequate capacity for several decades into the future, nevertheless it’s virtually guaranteed that eventually it will not be able to meet Austin’s growing transit ridership market at some further point. Should Austin be designing a system for that far into the future? Perhaps, but this “future-proofing” strategy needs to be weighed against other considerations, such as Austin’s available bonding capacity, and the need for such a project to be competitive for relatively scarce FTA capital investment grant funding.

A downtown subway project could still be undertaken at the point of unavoidable need, 40 or 45 years from now. Salvageable surface trackage and facilities could possibly be redeployed for a surface circulator system.

Economic development potential

But capacity and operational characteristics are not the only aspects of such a major urban rail investment to be considered. Light rail – either surface or subway – can be expected to catalyze significant nearby and adjacent economic development that potentially could provide a revenue stream recompensing most, or even all, of the infrastructure investment. The tens of billions of dollars in economic development stimulated by new LRT systems in cities like Los Angeles, Dallas, Portland, Phoenix, Charlotte, Seattle, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Kansas City, Detroit, and others represent abundant evidence of these benefits.

It’s worth imagining that LRT stations (either subway or surface) in downtown Austin could stimulate the development of a major underground/above-ground commercial/shopping complex there, directly connecting with the LRT system. Models of such developments, with stores, small shops and boutiques, theatres, restaurants, and other attractions, can be found in an array of global cities with signature core-area LRT systems or metros, whereby the urban rail system provides fast, easy access to these work, shopping, dining, and recreational opportunities. Several examples include:

• Los Angeles — The Bloc (connecting to Metro and LRT subways)

• Dallas — Dallas Pedestrian Network (underground concourses with shops, food services connecting to DART LRT)

• Toronto — Massive PATH underground shopping complex connecting with six TTC subway stations, including Union Station, the city’s largest transit hub

• Montreal — Underground City, “a multi-level network of tunnels and stairways that connect various shopping malls, metro stations, offices, hotels, libraries, schools, concert halls, and restaurants” (Culture Trip)

• Edmonton — The Pedway, a network of underground concourses and aerial walkways connecting over 40 office buildings, shopping centers, and parking facilities with three LRT stations in the downtown area

And of course there are numerous other examples worldwide of similar downtown complexes integrated with urban rail stations.

Whether Project Connect’s final plan includes a subway or not, the opportunity to design Austin’s LRT stations to catalyze economic development must be a major element. And especially with this city’s role as an internationally known venue for events such as SxSW, ACL, and Formula One, the chance to transform and enrich downtown with such a major integrated complex of activity centers with urban rail should not be missed.

■

Leave a comment