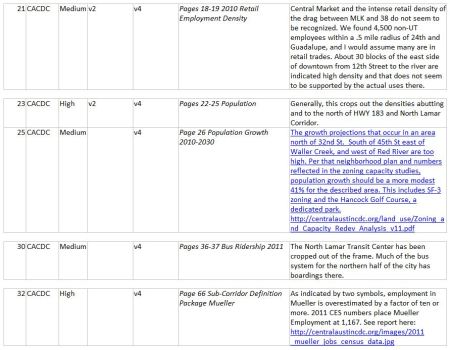

Commuting passengers deboard a MetroRail train. During SXSW, passengers have jammed onto trains, setting new ridership records. Photo: L. Henry.

♦

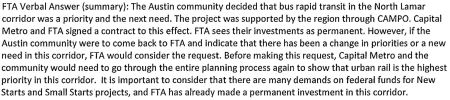

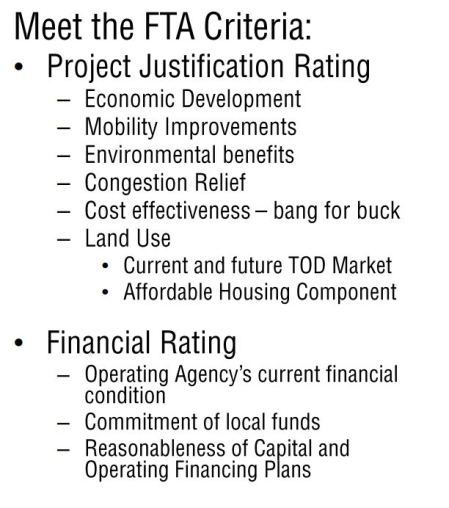

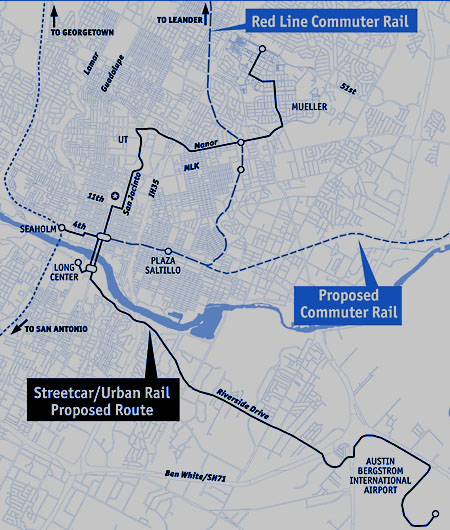

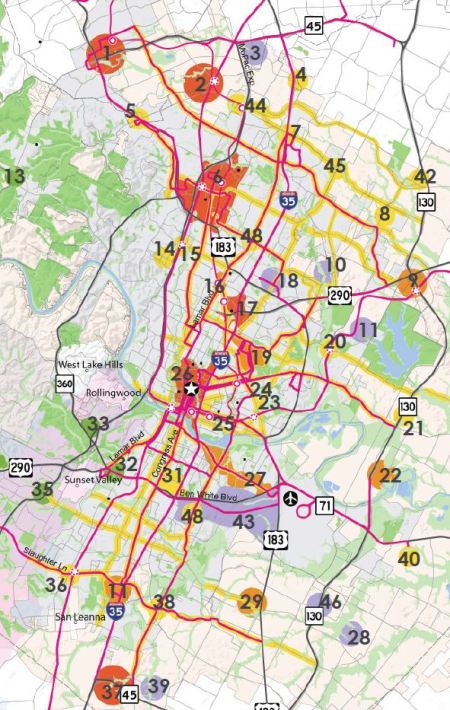

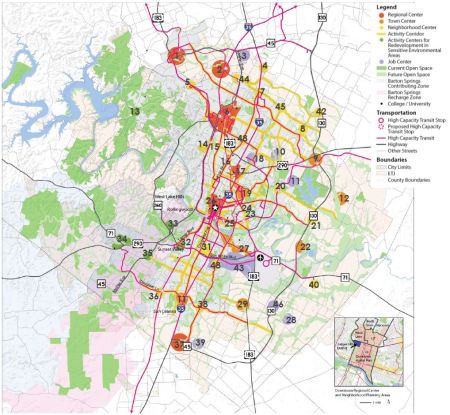

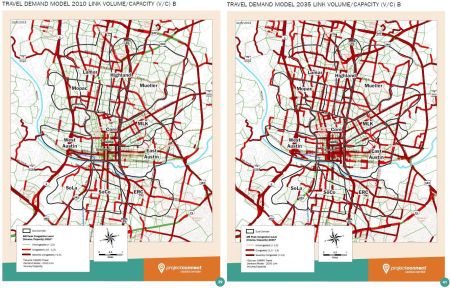

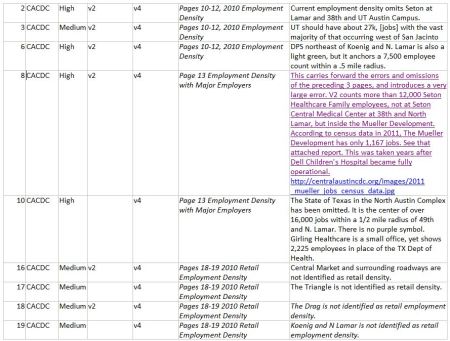

For at least most of the past year, as this blog has been noting, Project Connect has gradually shifted away from promoting “urban rail” (light rail transit, LRT) and more into emphasizing the delights of an abstract, amorphous mode of travel they’re calling “high-capacity transit”, which can supposedly range from dressed-up buses running in mixed traffic (MetroRapid) to actual high-capacity trains or railcars running on tracks.

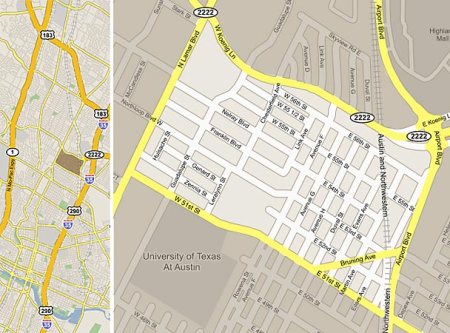

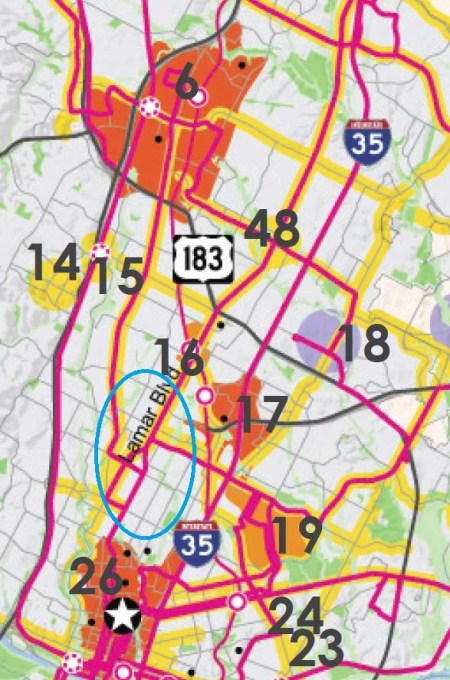

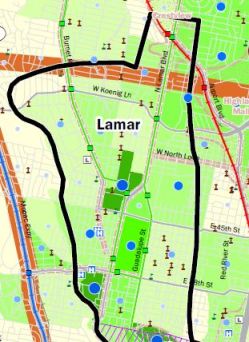

In Project Connect’s schema, the impression is conveyed that it’s all the same — rubber-tired buses running on the street, or trains running on tracks, either will do the same basic job. So, for the Guadalupe-Lamar (G-L) corridor, where Capital Metro launched the first MetroRapid route this past January, the new bus service has been christened “bus rapid transit” (BRT).

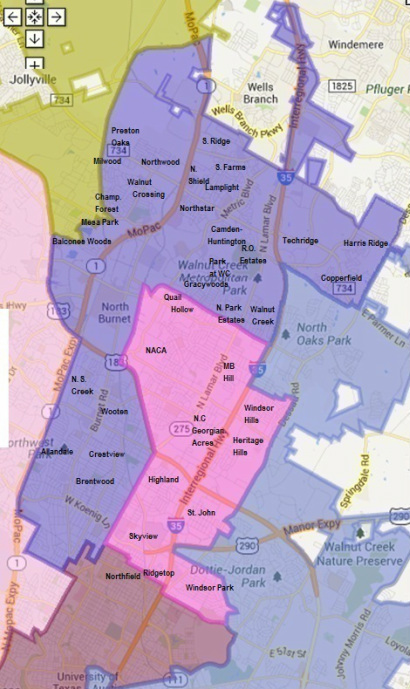

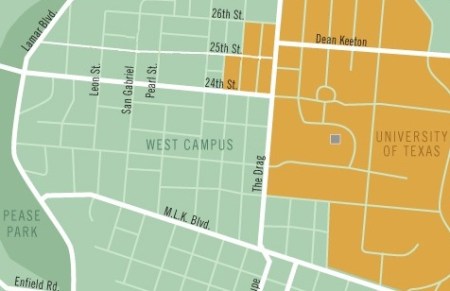

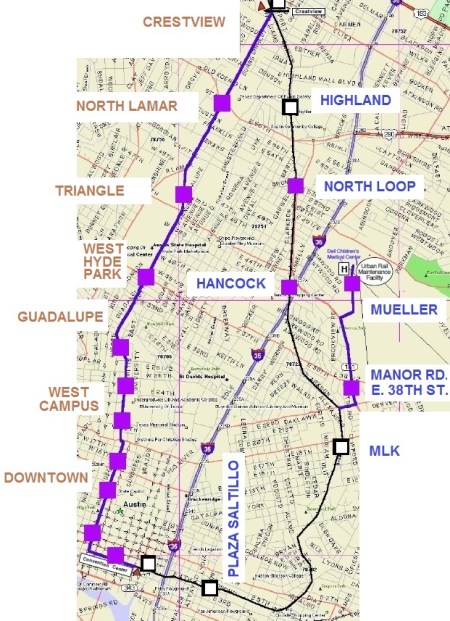

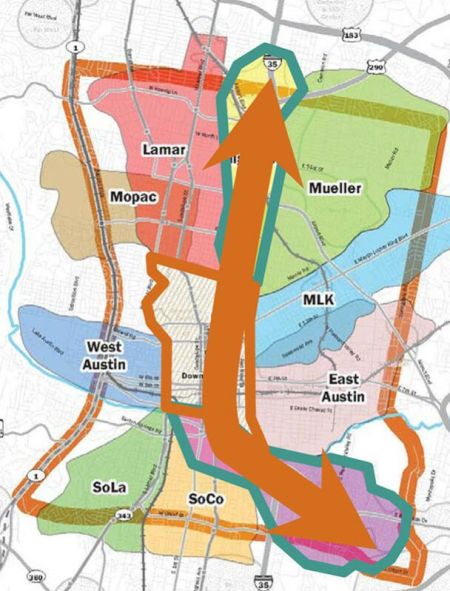

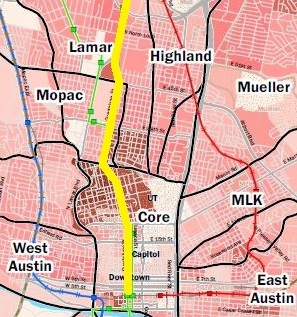

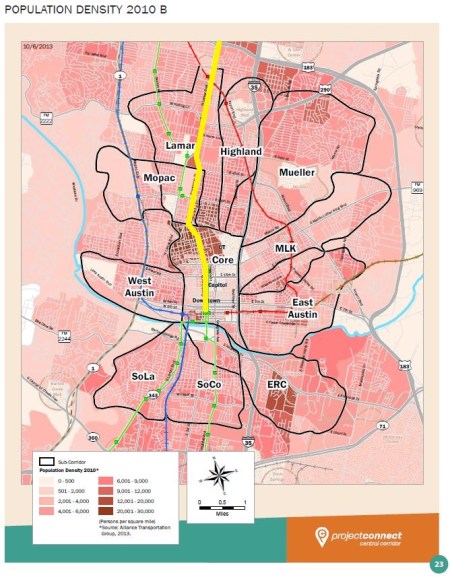

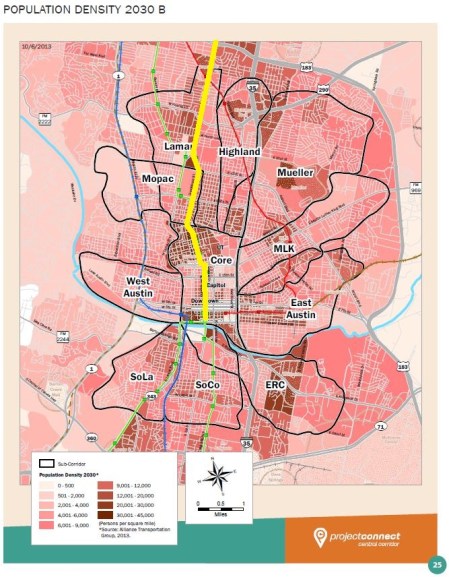

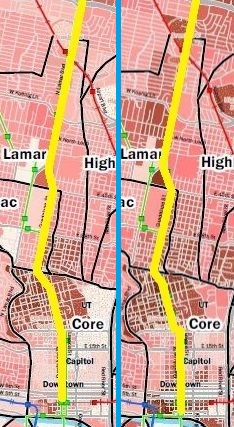

This has occurred in the midst of Project Connect’s jaw-dropping campaign to forsake the City of Austin’s long-standing commitments of urban rail for core neighborhoods and commercial activities along the heavy-traffic Guadalupe-Lamar and the high-density West Campus, in favor of serving the much weaker East Riverside area and a virtually non-existent “corridor” connecting downtown, the relatively backwater East Campus, Hancock Center, and the old Highland Mall site (now becoming a major ACC campus). Curiously, more than half of the “Highland” route replicates the previous Mueller route that had already sparked enough controversy to force Project Connect to embark on its “study” charade last summer.

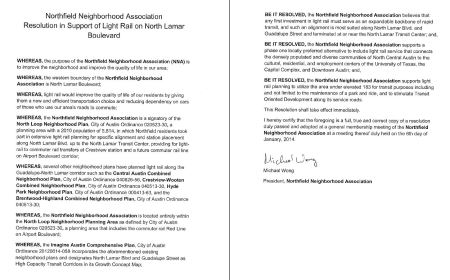

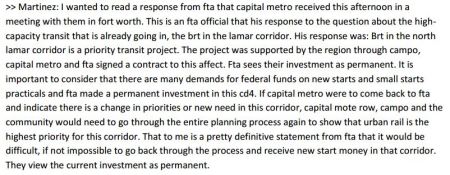

As the debate heated up over Project Connect’s very dubious “study” and subsequent decision to proceed with the Riverside-Highland route, neighborhood residents and other supporters of the G-L route found themselves repeatedly lectured that they should be satisifed with the spiffy new MetroRapid bus service they were getting — just like rail, but cheaper, it was implied. And in any case, these buses are so “permanent”, you can just forget any urban rail for decades, so just take it and accept it.

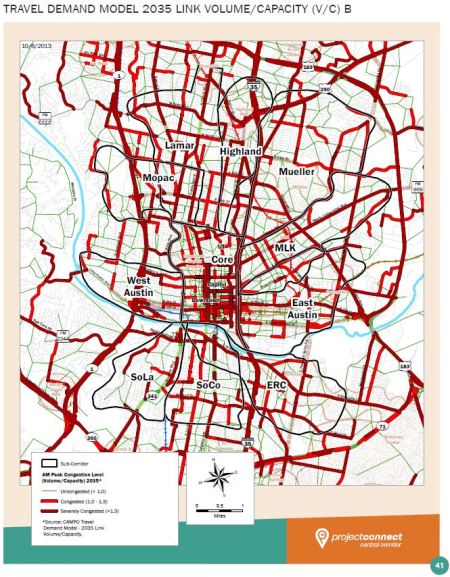

Meanwhile, after launching MetroRapid bus (accompanied by a rather low-key ceremony with invited guests) in late January, CapMetro encountered a swarm of new problems, mainly (1) widespread passenger irritation over the disruption and degradation of previous bus service in the corridor, (2) complaints over the tendency of MetroRapid buses (with no fixed schedule. but supposedly about 10 minutes apart at peak) to bunch up (leaving many passengers waiting 20 minutes), and (3) a decidedly unexcited public reception of the new service — prompting CapMetro to issue a steady stream of marketing pitches on Twitter and in other media attempting to persuade the public to try the service. And despite CapMetro’s hoopla, the fact remains that MetroRapid buses run almost entirely in mixed traffic, often congested, and it’s arguable that the actual level of service has been degraded, not improved. (Also see: Is Capital Metro’s New MetroRapid Service Leaving Bus Riders Behind?)

MetroRapid bus at a stop on the Drag. Passengers have not crowded aboard the new service as they have on MetroRail. Photo: L. Henry.

… Which brings us to Austin’s famous South by Southwest (SXSW) annual extravaganza March 7th-16th in the city’s core area. With a daunting array of street closures and street-fair-style activities, local transportation officials’ efforts to encourage people to leave their cars elsewhere and ride transit are virtually a no-brainer. And, by Project Connect’s schema, besides regular buses, visitors have had two major choices in “high-capacity transit” to choose from in getting downtown: the brand-new, MetroRapid service with its spiffy-looking, red-and-grey articulated (“bendy”) buses, and MetroRail, CapMetro’s “commuter” light railway with its large, comfortable, smooth-riding railcars, now in their fourth year of service.

The choices that SXSW transit riders have made, the object of media attention and other indications of public excitement, and reports from CapMetro via Twitter and other media have spoken volumes about what kind of “high-capacity transit” mode — rail or MetroRapid bus — generates real excitement and is most preferred by the public. And it ain’t MetroRapid bus.

Overwhelmingly, it’s been CapMetro’s MetroRail rail transit trains that have been crowded with passengers, and it’s been MetroRail that has gotten nearly all the focus of favorable news coverage and other attention. And that should give you some idea of why so many neighborhoods, UT students, and others along the G-L corridor are clamoring for urban rail, not a faux “bus rapid transit” substitute, to provide the high-quality transit service they need.

Typical of news coverage during SXSW was a KXAN-TV report Web-posted with the headline “Additional road closures during SXSW push more people to take MetroRail”.

“During South by Southwest, traffic jams are not unusual…” observed the reporter. “But for those who live here, trying to get to and from work can be even more frustrating than usual.”

One commuter, Shermayne Crawford, told the reporter: “I drove to work Monday and I think it took me an hour and a half to get home.” Because of that, explained the reporter, “She decided she would be using MetroRail for the rest of the week.”

“It’s worth taking it. It moves fast…” said Crawford. “It’s a little packed this week but overall I’ve been able to get a seat and enjoy myself on my way to work.”

According to a report by KUT-FM radio, MetroRail has been experiencing record ridership during the festival, with boardings “up from last year by almost 7,000” just in “the first several days” according to CapMetro. .

Capital Metro even had to operate an additional train after hours to carry more than 100 passengers still waiting on the platform. The trains on Saturday are starting at 10 a.m. – a few hours earlier than usual.

Perhaps nothing better highlights the enthusiasm of SXSW visitors for MetroRail’s train service than CapMetro’s own announcements and news bulletins. For example, on its website the agency posted:

Extended MetroRail Service

We know MetroRail is popular for traveling downtown during SXSW. We’re expanding our regular MetroRail service to help ease congestion:Extra service on Saturday, March 8 and 15 (10 a.m. – 2 a.m.)

Additional trips all day, March 10-14

Monday – Tuesday, March 10-11: 6 a.m. – 7 p.m.

Wednesday – Thursday, March 12-13: 6 a.m. – 12:30 a.m.

Friday, March 14: 6 a.m. – 1 a.m.Friday & Monday, March 7 & 17 – Regular schedule

No MetroRail service on Sunday, March 9 & 16

See the extended schedule tables below for exact times.

Our train is popular, so expect some crowding onboard. What can you do if the train’s full?Cyclists encouraged to use at-station bike racks

Check our Trip Planner or station signage for alternative routes downtown, many bus routes accessible within a few blocks

As the crush of passengers on the trains grew, in some cases causing delays, CapMetro labored to keep riders informed and assured that the service was being maintained, via an avalanche of nearly frenzied Twitter news feeds. Here’s just a small sampling from the past several days:

Capital Metro @CapMetroATX 19h

It’s 2 AM & you still have one more chance to ride the #MetroRail during #SXSW. Last Northbound train from Downtown Station departs at 2:19.Capital Metro @CapMetroATX 20h

MetroRail experiencing delays of approx. 20-25 mins. due to overcrowding & operating additional trains. Trains at capacity. #MetroRailAlertCapital Metro @CapMetroATX 21h

Though the clock has hit midnight, #MetroRail is still going strong. Last Northbound train from the Downtown Station is at 2:19 AM.Capital Metro @CapMetroATX 21h

MetroRail experiencing delays of approx. 15-20 mins. due to overcrowding & operating additional trains. Trains at capacity. #MetroRailAlertCapital Metro @CapMetroATX 22h

MetroRail currently experiencing delays of approximately 10-15 minutes due to overcrowding & operating additional trains. #MetroRailAlertCapital Metro @CapMetroATX 25h

MetroRail is currently experiencing delays of 15-20 minutes due to overcrowding. #MetroRailAlertCapital Metro @CapMetroATX 26h

MetroRail experiencing delays of approximately 10-12 minutes due to overcrowding & operating additional trains. #MetroRailAlertCapital Metro @CapMetroATX 28h

Be aware: Trains have been packed this #SXSW! It’s a great way to get around, but expect crowds and possible waits at platforms all day.Capital Metro @CapMetroATX Mar 15

Parking and riding? Temp. #SXSW MetroRail parking available at Kramer at City Electric Supply on 2540 Brockton Dr.Capital Metro @CapMetroATX Mar 15

Rail riders: MetroRail frequency being bumped up, service every 34 mins ALL DAY this SXSW Saturday to ease crowds: http://bit.ly/1lFtEH4Capital Metro @CapMetroATX Mar 15

MetroRail is running on a 15-20 min. delay at this time. Thanks for your patience. #MetroRailAlertCapital Metro @CapMetroATX Mar 15

MetroRail is currently operating on a 15-20 min. delay due to overcrowding. #MetroRailAlertCapital Metro @CapMetroATX Mar 15

MetroRail is currently operating on a 15 min. delay due to overcrowding. #MetroRailAlertCapital Metro @CapMetroATX Mar 15

FRI 3/14: See tonight’s MetroRail schedules here: http://www.capmetro.org/sxsw.aspx?id=3262#scheduletables …. #MetroRailAlert ^APCapital Metro @CapMetroATX Mar 14

MetroRail is experiencing 15 min delays due to crowds and running an extra train. #MetroRailAlert

To be fair, CapMetro’s buses have also seen strong ridership. As the above-cited KUT report recounts,

The bus service has also been popular. Capital Metro could not provide preliminary figures on ridership, but the transit company says many buses have been at full capacity.

However, next to no mention of the previously much-vaunted MetroRapid bus service. That new “bus rapid transit” operation? No reports of crowding, no extra service rollout, no media excitement. No frenzy of Twitter feeds or other media messages from CapMetro.

It’s trains, not dressy buses, that have drawn the crowds aboard and captured news media attention.

Keep in mind, however, that urban rail — using electric light rail transit trains — would be vastly superior even to MetroRail’s diesel-powered service. Instead of MetroRail’s circuitous “dogleg” around the heart of Austin and into lower downtown, urban rail trains would ride straight down Lamar and Guadalupe, able to make more stops and offer faster service because of their electric-powered acceleration. And they’d also be cheaper to operate.

As in this example from Houston’s light rail system, urban rail would be powered by electricity and operate mainly in the street — in Austin’s case, Guadalupe and Lamar. Photo: Peter Ehrlich.

However, MetroRail at least gives a taste of the advantages of rail transit. And the SXSW experience has provided a de facto “test case” of MetroRail and MetroRapid bus running more or less “head-to-head”, providing somewhat “parallel” transit service opportunities. And it certainly looks like the one rolling with steel wheels on steel rails wins.

That should give a clue as to why supporters of urban rail for Guadalupe-Lamar are far from satisified with being given a bus “rapid transit” substitute for bona fide LRT. One would hope that Project Connect, CapMetro, and City of Austin officials and transportation planners would get the message.

But even if they don’t, maybe Austin voters will.