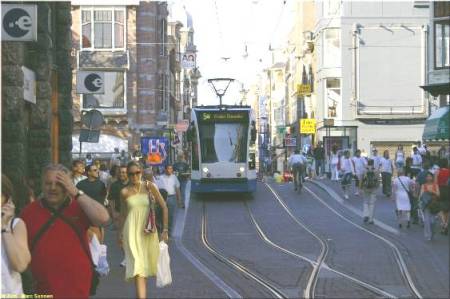

Amsterdam’s Leidsestraat shows how gauntlet track allows bidrectional light rail operation in a very narrow alignment, even with very close headways. Also remarkable is how smoothly, efficiently, peacefully, and safely the tram line blends in with, complements, and serves all the pedestrians who walk alongside, behind, and even in front of the trams. Photo: Roeland Koning .

♦

by Dave Dobbs

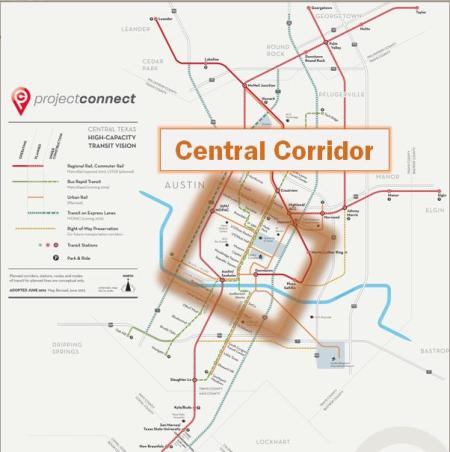

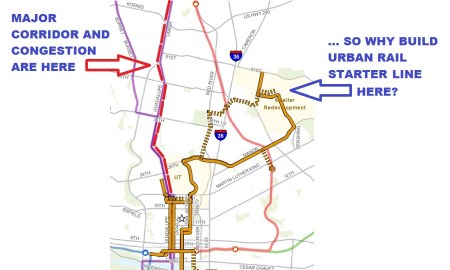

In the recent posting How urban rail can be installed in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor (Oct. 10th), Lyndon Henry discussed how urban rail in the Guadalupe-Lamar (G-L) corridor could deal with right-of-way constraints. For especially confined, narrow stretches, Lyndon suggested that interlaced, or gauntlet, track was an option.

Basically, gauntlet track works like a single-track section, but it doesn’t require movable switchpoints. Instead, it’s completely stationary, with one track in one direction overlapping, or interlacing, with the track in the opposite direction. Then, when the right-of-way becomes wider, the two tracks divide back into separate tracks in each direction again.

To expand on what Lyndon has explained about dealing with constrained rights-of-way (ROW) and the use of interlaced or gauntlet track, probably it’s helpful to focus on perhaps the most famous example — the Leidsestraat, a very narrow street in Amsterdam. This is a city filled with trams (aka streetcars, light rail).

Two views of the Leidsestraat. LEFT: A #1 tram, heading away from camera, has just left the interlaced section onto double track, passing a #5 tram headed toward the camera and the interlaced section. (Photo: Stefan Baguette) RIGHT: You can see the steady stream of trams, sometimes just a couple of minutes apart, passing the heavy flows of pedestrians on each side. (Photo: Mauritsvink)

In Europe, the tramway is basically surface electric urban rail (light rail transit) that can adapt like a chameleon — it is what it is, wherever it is. Flexibility is its trademark and it’s designed to fit within a budget.

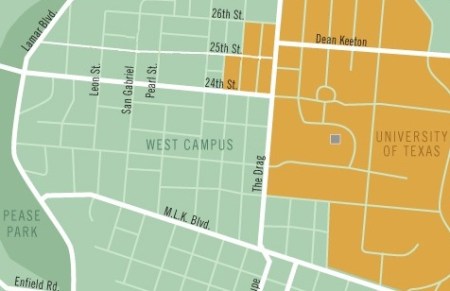

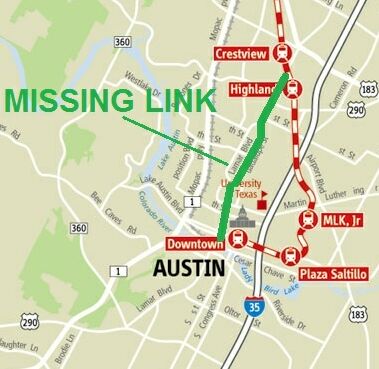

The Leidsestraat is about a third of a mile long in the center of the city and is home to three GVB (transit agency) tram lines running bi-directionally two to three minutes apart (see map below). Trams run constantly back and forth, sharing the gauntlet (interlaced) sections one at a time, and passing one another where the tracks branch out into double-tracked sections, where the street appears to be less than 40 feet (12-13 meters) wide.

Leidsestraat alignment runs about 500 meters (0.31 mile) in length, passing over several canals. Map: Dave Dobbs (from Google Maps).

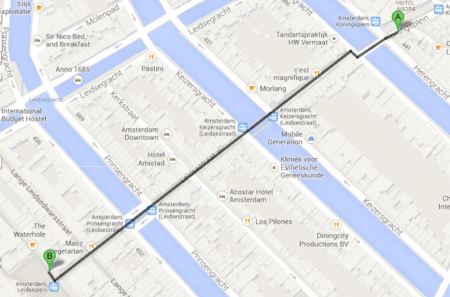

Light rail operation in the Leidsestraat is even more remarkable when you consider that it’s one of the busiest autofree streets in the world, teeming with pedestrians and bicyclists (as you can tell from the photos). Motor vehicles are allowed very limited access to serve retail stores, restaurants, and other businesses. Besides how well gauntlet track works with relatively close headways, allowing light rail trains to access this extremely narrow urban street, is how smoothly, efficiently, peacefully, and safely it blends in with, complements, and serves all the pedestrians who walk alongside, behind, and even in front of the trams.

The following are some additional photos of light rail tramway operation along this alignment

♦

Another photo showing crowds of pedestrians, an approaching tram, and a clearview of a transition from double-track to interlaced track. (Photo: Marc Sonnen.)

♦

Focus on interlaced track construction in the Leidsestraat. Notice how the two tracks virtually merge to form what almost seems like a single track — but there are separate parallel rails for each direction, laid next to each other. Also, only one rail in each direction actually crosses the other (this type of passive, stationary rail crossing is called a frog). Photo: Revo Arka Giri Soekatno

♦

Interlaced track is also used in other narrow locations, some shared with motor vehicle traffic. Here a Route 10 tram leaves the interlaced track over the Hoge Sluis bridge, as an autombile waits to proceed over the same right-of-way. (Photo by TobyJ, via Wikipedia.)

♦

Here’s an excellent 2-minute video showing trams operating in both directions into and out of one of the interlaced sections through the Leidsestraat.

Original YouTube URL:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gv9Vgo_W0HU

For further information, this link to Wikipedia’s article on Trams in Amsterdam may be helpful:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trams_in_Amsterdam

Special thanks to Roeland Koning and his Studio Koning photography service for his kind permission to use his photo of the Leidsestraat at the top of this posting. Visit his website at: