Because design and implementation dollars have been invested wisely, Denver’s light rail system increasingly resembles a network that’s expanding to serve more crucial corridors in the region. High ridership has also attracted transit oriented development (TOD) near stations, helping influence urban growth patterns. Map: RTD.

♦

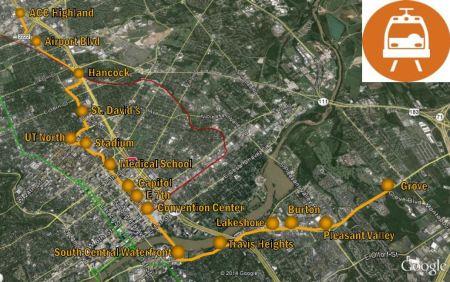

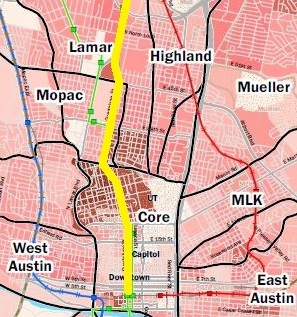

For the most part, Austin’s business and civic elite seem to have closed ranks around Mayor Lee Leffiingwell (“The Lee Team”) and his administration’s efforts to promote a very pricey 9.5-mile, $1.4-billion urban rail project widely suspected to be concocted more as a giveaway to the development ambitions of the University of Texas and a faction of private developers, and less as a remedy for alleviating Austin’s most serious mobility deficits. Included in this “business and civic elite” is virtually the entirety of the local media establishment.

But occasionally there are fractures in this ostensibly solid consensus, and one of these is represented by Jan Buchholz, an Austin Business Journal staff writer who seems to have the professional role of a de facto guru specializing in real estate market happenings. In a May 7th column, comparing urban development and transportation in Denver and Austin, she seems very favorably impressed with Denver, a model from which Austin, in her estimation, falls far short.“Rejuvenated neighborhoods are cropping up across Denver and development is being defined in many instances by the evolution of public transit” she writes. But unfortunately, “This dynamic does not exist in Austin to any great degree, and there’s little evidence that transit will play a significant role here any time soon.”

The reason? Mainly that Project Connect’s urban rail plan is pretty crummy:

The latest rail plan rolled out … is a $1.4 billion project that will run from Highland Mall to East Riverside Drive. Already, folks are decrying its high cost, but I don’t think it’s the cost that’s the real issue. It’s the fact that it’s a very small plan benefiting a limited group of people. That makes this price tag hard to swallow.

One of Buchholz’s gripes is that the proposal, which runs a short way southeast, ends way short of the region’s ABIA airport. And while local politicians are talking about “sweetening” the urban rail ballot measure with some dollops of highway projects, Buchholz doesn’t feel the highway capacity element is enough. (For the record, Austin Rail Now believes the Austin area’s emphasis on highway expansion is excessive, and should be ended.)

In regard to Denver’s urban rail development, Buchholz admires how the Mile-High City has prudently and energetically installed and expanded its system:

During the past 20 years, the Denver Regional Council of Governments — with support from a wide spectrum of stakeholders from government officials to businesses and residents — has embraced a huge vision for transportation improvements across the five-county metro area. It was never an easy sell, but for the most part taxpayers have supported the expensive, time-consuming and often inconvenient plan.

… The light rail is fully built out to the south, southeast and western suburbs. Construction is in progress for the light-rail line from downtown Denver to Denver International Airport, and another line will be built to the northwest suburbs.

Rejuvenated neighborhoods are cropping up across Denver and development is being defined in many instances by the evolution of public transit.

This dynamic does not exist in Austin to any great degree, and there’s little evidence that transit will play a significant role here any time soon.

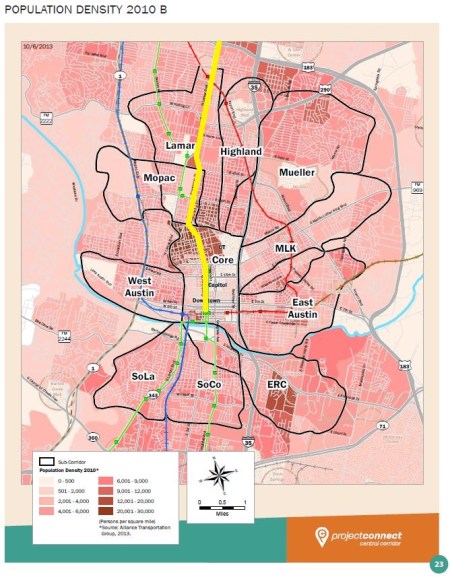

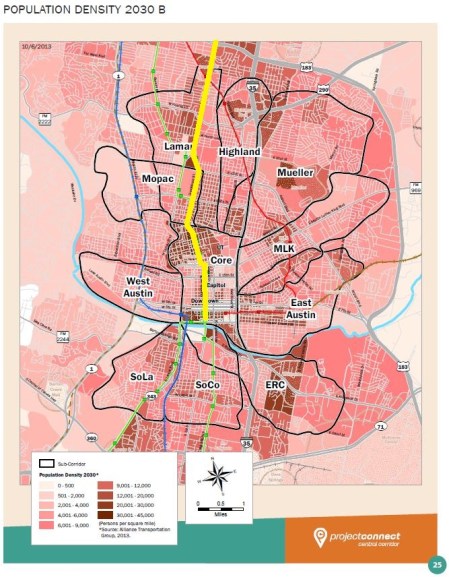

What’s critical to understand is that, from the start, Denver planners and political honchos realized that resources were scarce and that the region’s first light rail transit (LRT) — i.e., urban rail — starter line had to be located where it would get the proverbial “best bang for the buck”. And they also realized that, to influence developers’ decisions and encourage transit-oriented development (TOD), rail lines would need to be routed to maximize ridership.

Yes, most rail stations often do attract some adjacent development. But it’s the potential volume of ridership — i.e. the traffic on the line — that carries the most influence on private developers’ decisions. The more people, the more residents and customers at your development, which in turn becomes more attractive in the real estate market.

Opening day of Denver’s West Line light rail extension to Golden, Colorado, April 2013. Photo: David Warner.

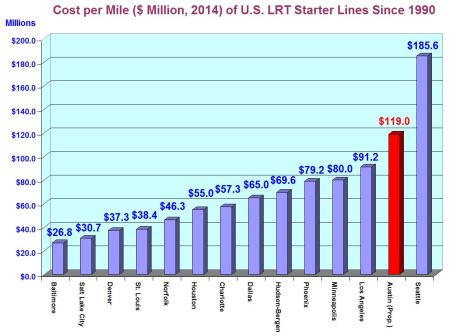

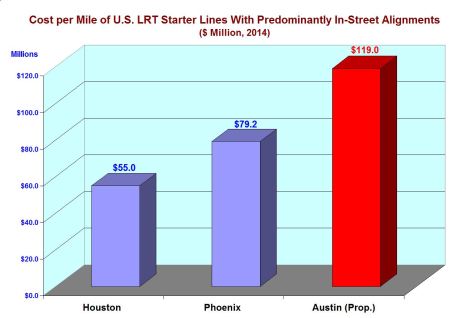

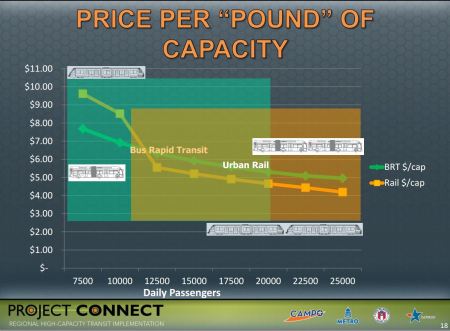

Key to urban rail expansion is conserving financial resources and deploying them wisely. Relatively lower outlays in the initial installation and operation of a new system means more funding available for expansion. So Denver started with a minimalist, 5.3-mile route from a northeastern neighborhood, proceeding down a busy corridor, via both street-running and a railway alignment, through a major commercial district, into the CBD, including a multi-institution university complex.

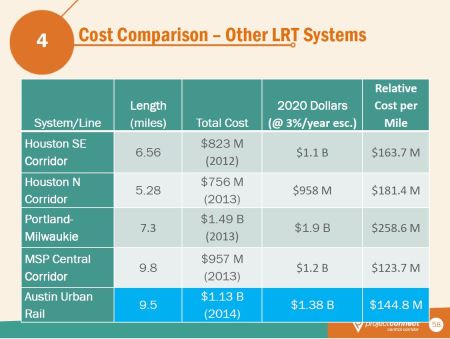

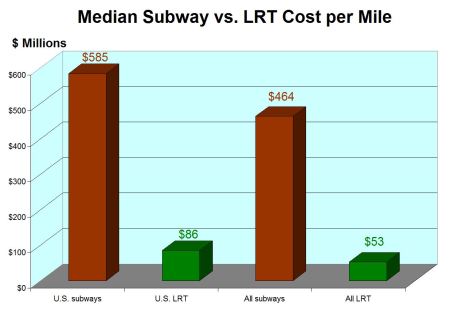

In 1994, they did that for $115 million. In 2014 dollars, about $37 million a mile. Compare that with Project Connect’s extravagant plan, including a tunnel and below-ground station, plus a “signature” bridge, at $119 million a mile. And Project Connect’s plan doesn’t even serve a major travel corridor!

Partly because they’d conserved financial resources, and partly because of the “big bang for the buck” effect that galvanized popular support, Denver’s Regional Transportation District (RTD) was able to embark on the vigorous urban rail expansion and TOD development program that so impresses Jan Buchholz. As a result, Denver’s light rail ridership mushroomed from 15,000 in 1994 to 86,900 a day by the end of 2013 — a nearly five-fold increase.

But Denver’s approach to urban rail has been virtually the polar opposite of Austin’s. Project Connect’s extravagantly wasteful billion-dollar starter line, with its peculiar, head-scratching route structure and high-dollar infrastructure, has divided potential urban rail supporters, pitting pro-rail community members and neighborhoods against one another in a way the pro-highway, anti-transit Road Warriors never could.

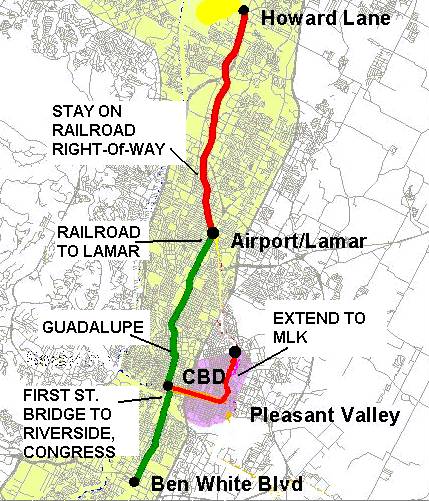

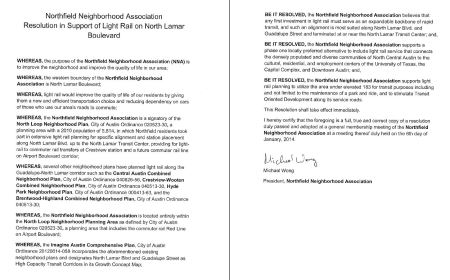

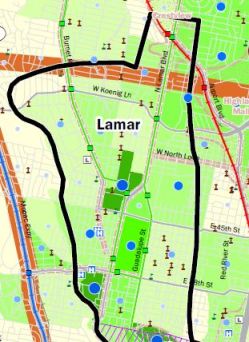

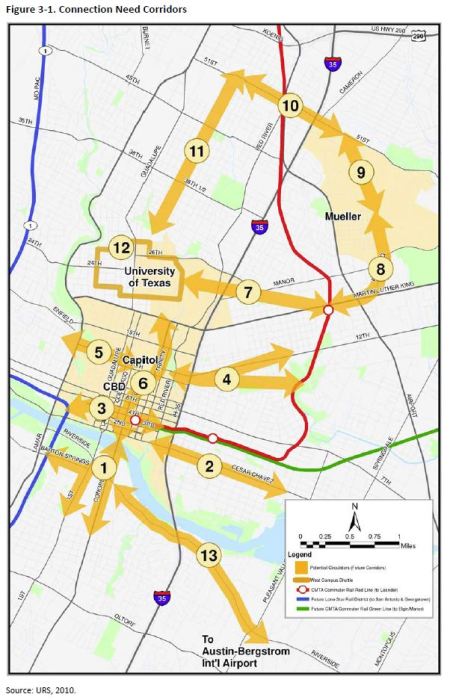

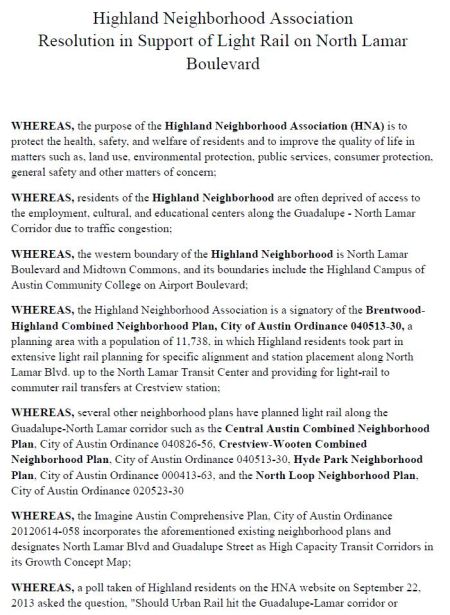

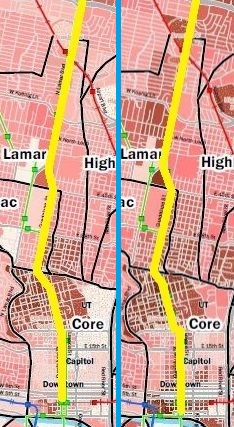

And the results are apparent in potential ridership. An alternative route for urban rail, long proposed for the heavily traveled, busy, dense Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, serving the high-density West Campus of the University of Texas, has been forecast to attract six times as much ridership as Project Connect’s meandering, peripheral line — at about 20% lower capital cost.

The prospects for voter approval of municipal bonds to finance Project Connect’s project are not sanguine. As Buchholz points out,

No one wants to be nickel and dimed to death for a mediocre and limited public transit system. Add to that the public perception that the MetroRail from Leander to downtown has been only marginally effective and has been fraught with issues from the get-go. Combine those two factors and this latest plan doesn’t have a chance for ever leaving the station.

If Austin has any hope of matching urban development and public transport successes like Denver’s it needs to start with an affordable urban rail starter line that makes sense. This notion seems to have “Lamar-Guadalupe-West Campus” written all over it. ■