LEFT: Denver’s starter LRT line, a 5.3-mile line opened in 1994, was routed and designed as a simple, surface-routed project to minimize construction time and cost. All-surface alignment avoided heavy, expensive civil works and kept design as simple as possible. Photo: Peter Ehrlich. RIGHT: Subsequent extensions, such as this West line opened in 2013, have required bridges, grade separations, and other major civil works, resulting in a unit cost 61% higher than that of the starter line. Photo: WUNC.org.

♦

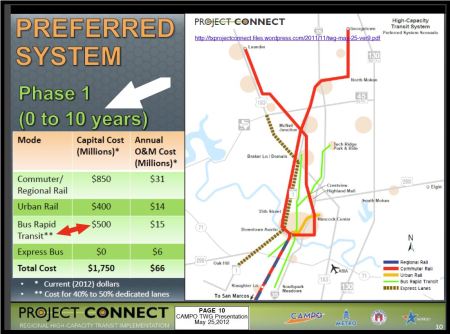

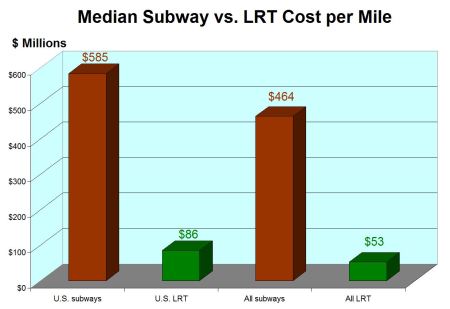

Since Project Connect released the cost estimates for their proposed 9.5-mile Highland-Riverside urban rail starter line last spring, agency representatives have tried to argue that the line’s projected cost of $144.8 per mile (2020 dollars) is comparable to that of other recent light rail transit (LRT) projects, citing new extensions in Houston, Portland, and Minneapolis.

Project Connect’s chart comparing their proposed Highland-Riverside “Austin Urban Rail” starter line cost to costs of extensions of several other mature light rail transit systems. (Click to enlarge.)

Austin Rail Now challenged this comparison In our recent analysis, Project Connect’s Austin urban rail would be 3rd-most-pricey LRT starter line in U.S. history. We argued that comparing the high cost of extensions of other, mature systems, was invalid, because urban rail starter lines tend to be much lower in cost than subsequent extension projects.

That’s because, in designing a starter line — the first line of a brand-new system for a city — the usual practice is to maximize ridership while minimizing costs through avoiding more difficult design and construction challenges, often deferring these other corridors for later extensions. In this way, the new system can demonstrate sufficient ridership and other measures of performance sufficient to convince both local officials and the public that it’s a success from the standpoint of being a worthwhile investment.

In contrast with starter lines, where officials and planners usually strive to keep design minimal and hold costs down in order to get an initial system up and running with the least demand on resources (and public tolerance), extension projects more often are deferred to later opportunities, mainly because they frequently contend with “the much more difficult urban and terrain conditions that are typically avoided and deferred in the process of selecting routes for original starter systems.” Deferring more difficult and expensive alignments till later also allows time for public acceptance, and even enthusiasm, for the new rail transit system to take root and grow.

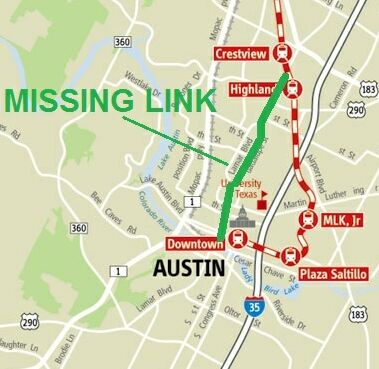

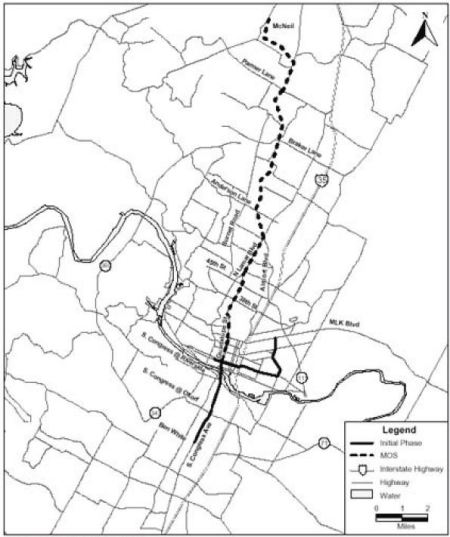

Austin’s case provides an illustration. As our article, Austin’s 2000 light rail plan — Key documents detail costs, ridership of Lamar-Guadalupe-SoCo route, describes, Capital Metro’s original 2000 LRT plan envisioned a “Phase 1” 20-mile system consisting of a 14.6-mile line from McNeil to downtown, plus a short branch to East Austin and a longer extension down South Congress to Ben White Blvd. In Year of Expenditure (YOE) 2010 dollars, that full system was projected to cost $1,085.8 million (about $1,198 million in today’s dollars). But a billion-dollar project was deemed too hefty a bite for the city’s first foray into rail, so decisionmakers and planners designated the shorter 14.6-mile northern section as a Minimum Operable Segment (MOS), with a more affordable (and, hopefully, more politically palatable)pricetag of $739.0 million in 2007 YOE dollars (roughly $878 million in current dollars).

After an initial starter line is established, for most subsequent extension projects the unit cost — per mile — tends to increase because, as previously indicated, officials and designers are willing to tackle more daunting corridors and alignments. Denver is a useful example.

In 1994 Denver established basic LRT service with a comparatively simple 5.3-mile starter line, running entirely on the surface in both dedicated street lanes and an available, abandoned center-city railway alignment, with an installation cost of $37.3 million per mile (2014 dollars). From that beginning, the system has been gradually expanded with increasingly more ambitious and more costly extensions. In 2013, Denver opened its West Line (the W line) to Golden; constructed over much more daunting terrain and obstacles, with multiple grade separations, bridges, and long elevated sections, plus more complex signal and communications systems and more elaborate station facilities. The West line was finished at a cost in 2014 dollars of about $59.9 million per mile — a unit cost about 61% higher than that of the original starter line.

Despite such evidence, at an Aug. 5th urban rail forum sponsored by the Highland Neighborhood Association, Project Connect’s Urban Rail Lead, Kyle Keahey, dismissed the assertion that starter lines were lower in cost per mile than extensions. Instead, he insisted, “the reverse is true.”

Really? But this claim is refuted even by the same cases that Project Connect has presented as peer projects for comparing the estimated $144.8-million-per-mile cost (2020) of its Highland-Riverside proposal.

In the following comparative analysis, we use Project Connect’s own year-2020 cost-per-mile figures for their selected “peer” projects. For each of those we use the starter line cost-per-mile data from our earlier May 8th article (cited above), plus data for Portland’s original starter line (a 15.1-mile line opened in 1986 from central Portland to the suburb of Gresham). These unit costs, in 2014 dollars, were then escalated to year-2020 values via the 3% annual factor specified by Project connect for their own table data.

The resulting comparison is shown below:

Using Project Connect’s selected LRT systems, this comparison shows that the cost per mile of new starter lines tends to be significantly less than the cost of later extensions. Graph: ARN. (Click to enlarge.)

Clearly, this analysis corroborates our original assertion — based on these cases, the unit costs of LRT starter lines tend to be considerably lower than the unit cost of later extensions when these have developed into more mature systems. And, at $144.8 million per mile, the unit cost of Project Connect’s proposed 9.5-mile Highland-Riverside urban rail starter line is certainly far higher than the cost of any of the original starter lines of these selected systems — all using Project Connect’s own cases and criteria.

Q.E.D., perhaps? ■