Congested I-35 traffic has Austinites desperate for a solution, but Project Connect’s Highland-Riverside alignment would have negligible impact. Photo via Austin.CultureMap.com.

♦

Project Connect representatives have been claiming an array of hypothetical benefits they say would result from their proposed Highland-Riverside urban rail project. Among these is “congestion relief”.

For the most part, this sweeping claim has been blurry, undefined, unquantified, and widely dismissed as ridiculous. (See Why Project Connect’s “Highland” urban rail would do nothing for I-35 congestion.)

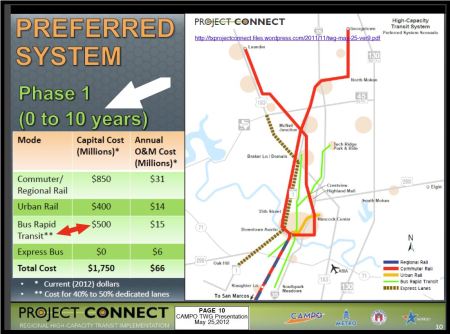

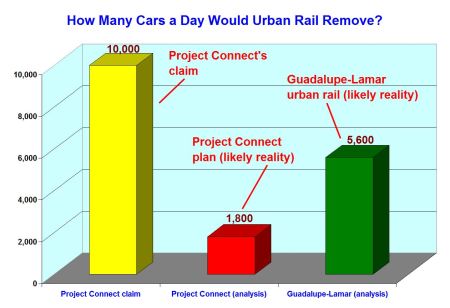

But in promotional presentations, Project Connect personnel and supporters have repeatedly touted one specific, numerically quantified purported benefit — the claim that their urban rail project “takes 10,000 cars off the road every weekday”.

Screenshot from Project Connect slide presentation claiming Highland-Riverside rail plan would remove “10,000 cars” a day. (Click to enlarge.)

This figure invites scrutiny. Project Connect has also been touting a 2030 ridership projection of “18,000 a day” — although this appears to rely on flawed methodology. (See our recent analysis Project Connect’s urban rail forecasting methodology — Inflating ridership with “fudge factor”? which, adjusting for apparent methodological errors, suggests that total ridership of 12,000 per weekday is more plausible.)

In any case, of its projected total weekday ridership, Project Connect also claims that only 6,500 are “new transit riders” for the urban rail line. (Project Connect also claims “10,000 new transit riders to system” — but typically these new “system” boardings represent the combination of the new rail rider-trips plus the same passengers using feeder bus routes to access the rail.) This is consistent with industry experience, since a sizable proportion of the ridership of new rail services consists of passengers that had previously been bus transit riders.

But this “new transit riders” figure, while plausible, immediately diminishes the plausibility of the claim of “taking 10,000 cars off the road”. How could 6,500 riders, boarding trains, eliminate 10,000 cars from the road?

Furthermore, the estimate of 6,500 rider-trips (i.e., boarding passengers) actually doesn’t equal 6,500 individual passengers, i.e., persons. Why? Because (as is commonly known and accepted in the industry) a very large percentage of those trips are made by the same, individual passengers — mainly round trips, or extra trips during lunch hour, and so on.

The count of daily “boardings”, or rider trips — i.e., ridership — is actually a tally, in U.S. industry parlance, of unlinked trips. These are the string of trips on transit made over a day by the same individual person; they might include trips on a feeder or connector bus to a rail transit train, possibly other trips during the day by transit, and perhaps that person’s return trips back home by the same modes.

So, how to figure how many individual passengers (persons) are actually involved in a given ridership figure? The American Public Transportation Association (APTA) suggests a conversion factor: “APTA estimates that the number of people riding transit on an average weekday is 45% of the number of unlinked transit passenger trips.”

Thus, applying that 45% factor to those 6,500 “new rider” trips, we realize that figure represents roughly 2,925 actual passengers projected to ride the proposed urban rail line, new to the transit system.

However, we cannot assume that every one of those new passengers would have used a motor vehicle rather than riding transit. On average, about 75% have access to a car. So 2,925 passengers X 75% = 2,194 passengers that could be assumed to leave their cars off the road to ride transit. (It’s pretty much a cinch that these hypothetical transit passengers wouldn’t be driving, on average, more than four cars a day!)

To estimate more realistically how many cars would be affected, we need to factor in average car occupancy of 1.2 persons per car (to account for some carpooling). That final calculation yields 1,828 — or (by rounding for level of confidence) roughly 1,800 cars removed from the road by Project Connect’s proposed urban rail plan.

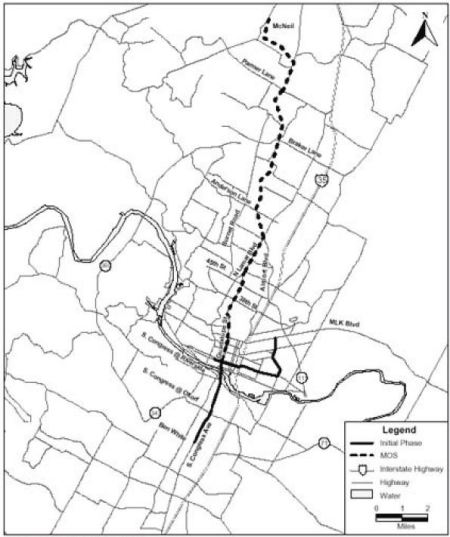

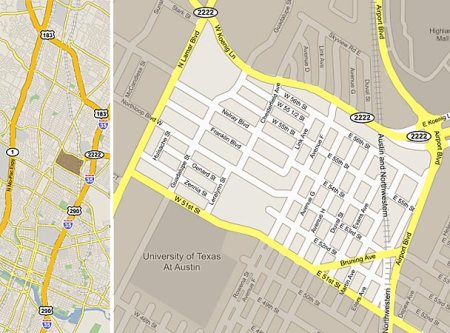

That 1,800 is an all-day figure. Using an industry rule-of-thumb of 20%, about 400 of those cars would be operated during a peak period, or roughly 100, on average, during each peak hour. As our article on I-35 congestion, cited above, indicates, the impact on I-35 traffic would be very minimal. Most of the effect of that vehicle traffic elimination would be spread among a number of major arterials — particularly Airport Blvd., Red River St., San Jacinto Blvd., Trinity St., and Riverside Drive. This impact on local arterial congestion would be small — but every little bit helps.

While the removal of 1,800 cars from central Austin roads is a far cry from 10,000, once again, every incremental bit helps. And there’s also the decreased demand for 1,800 parking spaces in the city center.

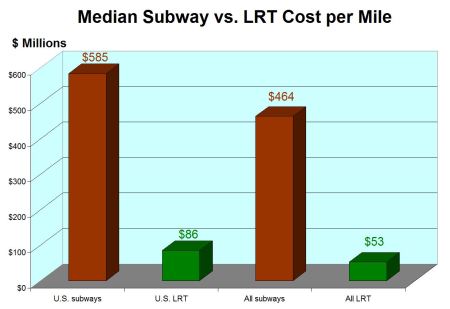

But the point is that $1.4 billion (about $1.2 billion in 2014 dollars) is a huge investment to achieve so little. For many cities, ridership at the level of 12,000 a day typically isn’t so bad, but when you’re missing the potential of 35,000-45,000 a day, plus incurring such a high cost for this level of payoff, you need to reconsider the deal. (For example, see Austin’s 2000 light rail plan — Key documents detail costs, ridership of Lamar-Guadalupe-SoCo route.)

For less than half of Project Connect’s urban rail investment cost, a “backbone” urban rail line on Guadalupe-Lamar (with a branch to the Seaholm-Amtrak area) could plausibly be expected to generate at least three times as much ridership — and eliminate roughly 5,600 cars a day from central-city streets and arterials.

Summary chart compares Project Connect’s claim of taking “10,000 cars off the road every weekday” vs. (1) ARN’s analysis of probable actual number of cars removed by Highland-Riverside line and (2) projected number of cars that would be removed from Austin’s roadways by alternative Guadalupe-Lamar urban rail plan. (Click to enlarge.)

Now, that’s some “congestion relief” worth paying for. ■