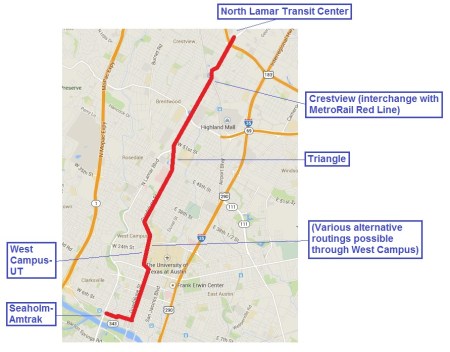

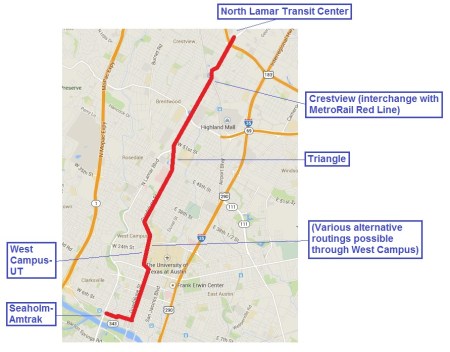

Red highlighting line demarcates North Lamar Blvd. and Guadalupe St., north-south central spine of Guadalupe-Lamar travel corridor. (Click to enlarge.)

Last October, in our article titled «Latest TTI data confirm — Guadalupe-Lamar is central local arterial corridor with heaviest travel», this website noted that “For years, many Austin public transit activists have been insisting that the Guadalupe-Lamar (G-L) corridor is the central inner city’s most heavily traveled local travel route, and should be the first priority for installing urban rail.” As the article further explained:

By far, the heavy travel flow in this corridor one of that most compelling features that cry out for the capacity, public attractiveness, and cost-effectiveness of urban rail (light rail transit, LRT). Study after study has documented the fact that this is the most intensely traveled inner-city local corridor — the only major corridor serving the city’s central axis between I-35 and Loop 1 (MoPac).

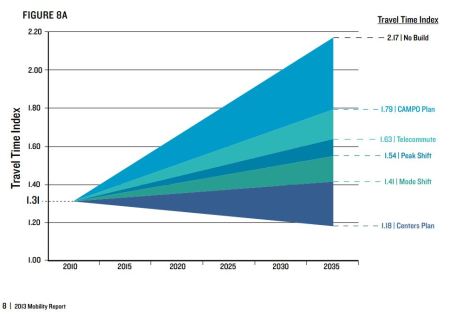

Now, the latest annual report of the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI), endorsed by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) not only strongly corroborates these assessments, but provides data that further emphasize the key importance of the G-L corridor.

The article summarized the TxDOT data with several graphs showing that, in both traffic and mobility congestion, Guadalupe-Lamar surpasses all other major local arterial corridors in the city. Conclusion: Once again, “Good sense suggests that Guadalupe-Lamar remains the top-priority corridor for an urban rail starter line.”

This conclusion merely corroborates a reality that has changed relatively little in more than 50 years — a saga of planning for this crucial central corridor that can be more fully grasped in the following series of maps spanning over five decades.

Central Freeway plan

As early as 1962, the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor was proposed as the route of a Central Freeway (also designated a Central Expressway) in a regional transportation plan produced by the Texas Highway Department (predecessor of the Texas Department of Transportation, TxDOT). The map below, an excerpt from the larger 1962 regional map in the official report, zooms in on roadways planned for central Austin, with proposed freeways shown as dashed red lines. We’ve annotated the Central Freeway in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor (running north-south just to the left of center) with an additional yellow line in the middle of the red.

Central Freeway (annotated here with yellow line in center of dashed red line). (Click to enlarge.)

The prospect of a new freeway slicing through established neighborhoods like Hancock, Hyde Park, and the West Campus eventually prompted interest in a rail transit alternative for the corridor. This is noted in the following information from the Texas Freeway website, which provides a verbal narrative of the proposed Central Freeway route:

Central Freeway Starting downtown just west of the Capitol, this freeway would have been located a block or two west of Guadalupe and proceeded northward up to the UT campus, where it would join Guadalupe and follow Guadalupe northward to Koenig lane. It then curved to follow the route of Lamar street. A light rail line was planned for this route in 2000, but was narrowly rejected by Austin voters in November 2000. In the long run, there is still a very good chance that light rail will be built on this route.

Past light rail plans

The prominence of the Guadalupe-North Lamar travel corridor, the need to effectively provide access to major core activity centers including the University of Texas campus, the Capitol Complex, and downtown, plus the looming prospect of a major freeway to cut through the heart of the city, prompted strong interest in exploring public transit alternatives. Starting in the 1970s, these began to emerge.

► CARTRANS proposal — The possibility of rail transit as an effective and plausible alternative to the Central Freeway for Austin’s central Guadalupe-Lamar corridor emerged decisively in 1973 via the release of A Preliminary Feasibility Study for a Capital Area Rapid Transit System (with the acronym CARTRANS). Prepared by Lyndon Henry, a leader of Texas Association for Public Transportation (TAPT), with the collaboration of Phil Sterzing, a former Austin city planner, the plan proposed a 19.2-mile electrically propelled light transit (LRT) line running in a subway and on elevated structure through the heart of the center-city, then on surface railway alignments north and south. (Lyndon Henry is currently a contributing editor to this website.)

CARTRANS report (left) proposed LRT 19.2-mile route (right) stretching from north to south Austin and paralleling major central flow of travel along North and South Lamar, South Congress, and I-35. Photos: ARN.

Published by the Washington, DC-based RAIL Foundation, the CARTRANS report quickly garnered interest and support from the Austin City Council and much of Austin’s top civic leadership. This catapulted rail transit — previously disparaged as inappropriate for any Texas city — into a possibility under serious consideration as a realistic public transit alternative for the central city.

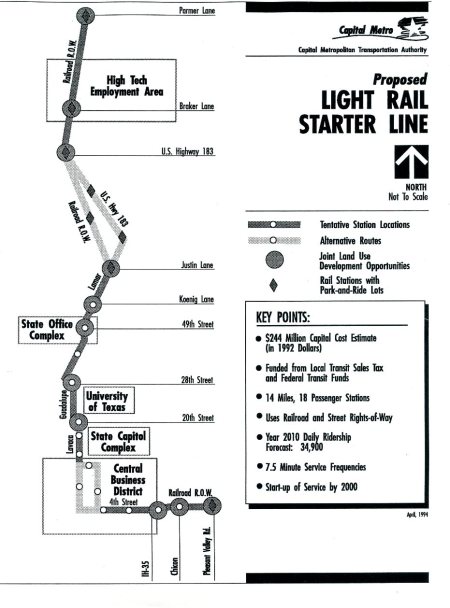

► Capital Metro planning in early 1990s — After approximately a decade of additional transit planning conducted mainly via the Austin Transportation Study, civic interest and public excitement over the possibility of an Austin rail transit system (particularly as an alternative to the metro area’s increasingly congested and dangerous roadways) helped facilitate creation of the Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority (CMTA, Capital Metro) in 1985. Subsequently, the agency’s initial major planning effort, the Transitway Corridor Analysis Project (TCAP), having concluded in 1989 with robust community involvement, led to the designation of LRT as the agency’s Locally Preferred Alternative (LPA, a federally required decision).

Also emerging from the TCAP experience was the concept of connecting access to the northwest metro area, via the City of Austin’s newly acquired railway line, with the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, serving multiple destinations, established and high-density neighborhoods, the University of Texas (UT), Capitol Complex, and downtown. In addition, most local transit advocates, including TAPT, as well as local planners and decisionmakers realized that a surface LRT system (rather than significant subway or elevated infrastructure) was best suited for Austin’s scale and financial resources.

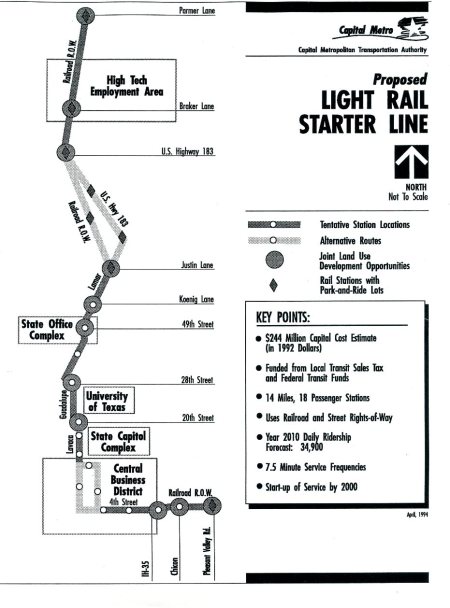

Beginning in the early 1990s, Capital Metro contracted with a consulting team led by E.P. Hamilton & Associates to conceptually design and evaluate a surface-routed electric LRT alignment to serve primarily the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor plus a segment of Austin’s northwest corridor, served by available “opportunity assets” including the now publicly owned railway line as well as the major arterials North Lamar and Guadalupe St. Also included was a short additional spur into East Austin, using a segment of the same CMTA railway. As with all such proposals, this was envisioned as merely a “starter line”, seen as the first crucial leg of an ultimately multi-route system serving the entire metro area.

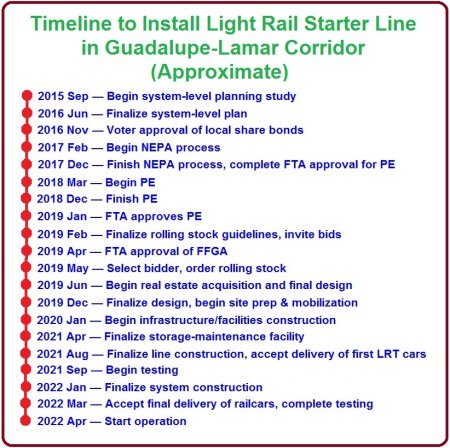

The eventual plan, finalized by a Light Rail Transit Station and Corridor Area Planning consultant team led by Carter Design Associates, in association with 6 other consulting firms, proposed a 14-mile starter line route running from Parmer Lane southward to the CBD. From Parmer to U.S. 183 the route uses the CMTA railway right-of-way; alternative routes using U.S. 183/North Lamar or the railway are proposed from there to Justin Lane; then the route follows Lamar, Guadalupe, and Lavaca into the CBD, with the already mentioned branch into East Austin. The plan was projected to have a total investment cost of $244 million (1992 dollars), with opening targeted for 2000, and daily ridership forecast as 34,900 in 2010. The route map and key features are summarized in the following informational page from Capital Metro, dated April 1994:

Capital Metro LRT plan for Guadalupe-Lamar and northwest, 1994. Map: CMTA. (Click to enlarge.)

► Capital Metro 2000 LRT plan — During the mid-to-late 1990s, Capital Metro changed course somewhat to focus on a possible diesel-operated rail service exclusively on the agency’s railway. Mainly because of this, and political and organizational upheavals at Capital Metro, the 1994 plan was effectively shelved … only to be resurrected, almost intact, in 1999-2000 by a reorganized Capital Metro board chaired by tech industry executive Lee Walker. In a charette convened by the agency, dozens of national transit industry professionals reaffirmed the primacy of the Guadalupe-Lamar and northwest travel corridors, and endorsed the need for a line very similar to the 1994 proposal.

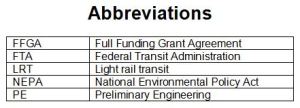

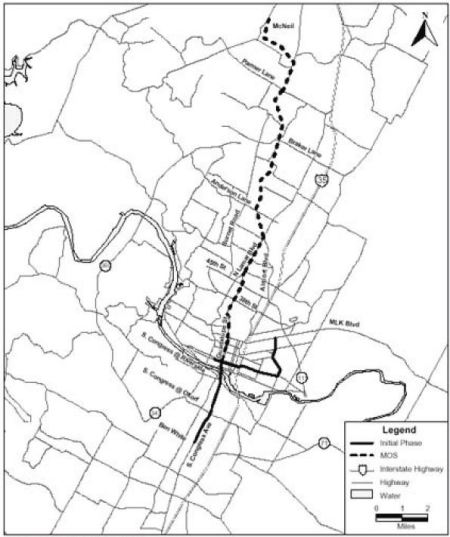

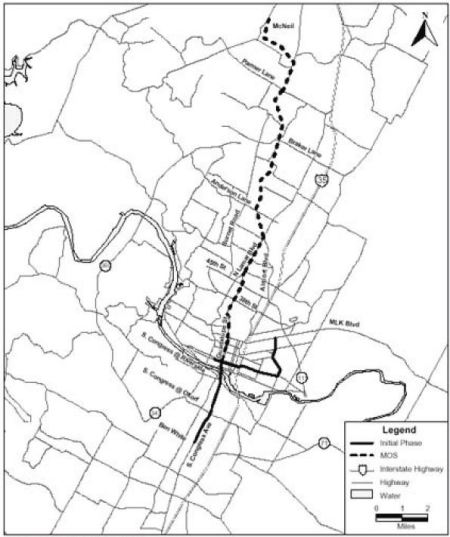

Assisted by the Parsons-Brinckerhoff consulting firm, Capital Metro planners devised an LRT plan intended to be funded 50% with Federal Transit Administration (FTA) grants. As described in our article «Austin’s 2000 light rail plan — Key documents detail costs, ridership of Lamar-Guadalupe-SoCo route», “Capital Metro’s proposal was sectioned into two parts — a shorter Minimum Operable Segment (MOS), running from McNeil Rd. in north Austin — using railway right of way (now used by today’s MetroRail), then Lamar-Guadalupe — to the CBD, and a full Phase 1 plan, which added a line down South Congress to Ben White, and another branch on Capital Metro’s railway right of way to Pleasant Valley Rd.”

The MOS (McNeil Rd. to CBD) consisted of a 14.6-mile initial starter line segment, with ridership for the forecast year (2025) projected at 37,400 per day. The complete Phase 1 plan — adding the South Congress (SoCo) extension, plus a branch into East Austin, comprised 20.0 miles of route. These are shown in the following map from the FTA’s New Starts report on the project:

Capital Metro’s 2000 MOS (dashed line) and full Phase 1 light rail plan. Map: FTA. (Click to enlarge.)

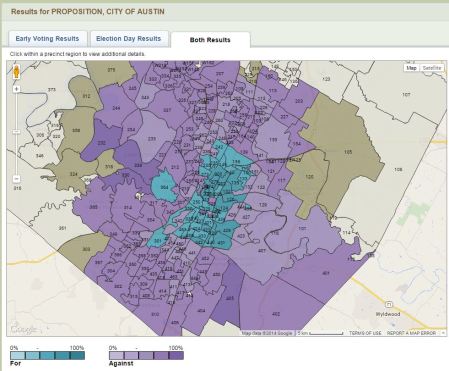

While Capital Metro’s LRT initiative was rejected in a November 2000 referendum, it lost by less than one percentage point — and actually got a solid majority vote within the City of Austin itself. This thread of public support would help keep the project alive.

► Rapid Transit Project planning — Because of the very narrow margin of the loss in the 2000 LRT plan vote, and the clear evidence of support from City of Austin voters, following the 2000 election Capital Metro and the City of Austin established a joint Rapid Transit Project (RTP) that continued planning, with a focus on the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor as well as a potential alignment on Capital Metro’s railway to the northwest. While several alternative segments were considered (including a subway option, which was discarded), the primary route through the heart of the central city remained Guadalupe-Lamar, as indicated in the following annotated map disseminated in April 2002 by the RTP:

Route alternatives considered by the City-Capital Metro joint Rapid Transit Project, as presented in 2002. Guadalupe-Lamar remained the heart of the plan’s route into the Core Area, as shown by the red line. Map: RTP. (Click to enlarge.)

During this period, intensive planning for LRT, particularly in the G-L corridor and downtown, continued, with vigorous public meetings and consultations. Included in these activities was the extensive involvement of community activists and residents of neighborhoods along the proposed route, much of it focused on developing and finalizing neighborhood station-area plans with the aim of effectively utilizing the anticipated resource of LRT.

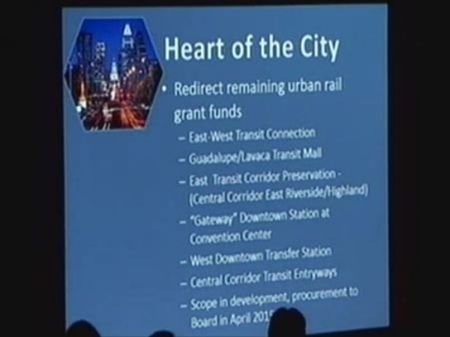

These planning efforts continued until the RTP’s activities were effectively curtailed and eventually terminated as Capital Metro abruptly ended planning for LRT in the G-L corridor in mid-2003 and turned instead to developing a diesel-operated “urban commuter rail” line (in effect, a revival of a very similar concept from the mid-1990s). That effort led to voter endorsement of the plan in November 2004, and the Red Line, rebranded as MetroRail, opened in the spring of 2010.

However, as this website has related in our Nov. 2014 article «Derailing the Mueller urban rail express — Preamble to Project Connect’s 2013 “High-Capacity Transit Study”», unlike the LRT plan that would run straight to Austin’s Core Area, the new diesel-multiple-unit (DMU) operated system lacked this access: “Since the newly approved DMU line ran on a railway alignment that bypassed most of the heart of the city, ending only at the southeast corner of the CBD, officials and planners realized they needed some way to connect passengers with key activity points, including UT and the Capitol Complex.”

This led officials and planners to try to solve the problem with various schemes, including “connector” buses, then the MetroRapid bus project, and some kind of rail “circulator” that would connect the commuter-like MetroRail with key destinations. As our article cited above explains, a streetcar scheme morphed into a more robust LRT concept that included both a route on East riverside Drive and a more central line running through the east side of downtown, UT’s East Campus on San Jacinto Blvd., and on into the Mueller site, first via Manor Road, then eventually via a route using Red River St., Hancock Center, and Airport Blvd. to access Mueller. Any vestige of LRT in the city’s most heavily traveled central local arterial corridor — Guadalupe-Lamar, including access to the West Campus and the business commercial district and established neighborhoods along it — was abandoned.

Current light rail plans

But while the obsession of Austin’s local political establishment and official planners had turned to a route apparently motivated in part by a desire to bolster real estate development plans at Mueller and East Riverside, and the UT administration’s East Campus expansion plans, local community activists and public transit activists continued to call attention to the abiding need for LRT in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. It was clear years ago, and now, that reliable data has continued to corroborate what Austinites can themselves see and experience — that this is the most important, heavily traveled local corridor in the heart of the city. See, for example, data cited in our articles:

• Demographic maps show Lamar-Guadalupe trumps Mueller route for Urban Rail

• Guadalupe-Lamar urban rail line would serve 31% of all Austin jobs

• Guadalupe-Lamar is highest-density corridor in Austin — according to Project Connect’s own data!

• Latest TTI data confirm — Guadalupe-Lamar is central local arterial corridor with heaviest travel

This community involvement, including the efforts of TAPT and the Light Rail Now Project, has led in more recent years to a series of alternative proposals for LRT/urban rail alignments in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, as described below.

► TAPT “loop route” — In May 2012, responding to an official proposal for a 5.5-mile, $550 million “urban rail” line running from downtown, through the East Campus, to Mueller, TAPT leaders Dave Dobbs and Lyndon Henry presented an alternative $700 million plan for 14.7 miles of LRT serving both the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor and the eastside Red Line corridor. Connected at both north and south ends where the west and eastside lines would converge, the route thus formed a “loop” around the heart of the city. A branch serving the Mueller site was also included. (When an estimated $150 million was added into the official “urban rail” plan — accounting for a projected “BRT” line in the G-L corridor — the TAPT “loop” proposal matched the cost of the official concoction of rail + “BRT”.)

The route proposed in this plan, described in our March 2013 article «An alternative Urban Rail plan», is illustrated in the original map below:

TAPT “loop” plan from the early summer of 2012 proposed a 14.7-mile route “looping” around the heart of the central city, including a line in the G-L corridor, plus a branch to Mueller. Map: TAPT. (Click to enlarge.)

► CACDC proposal — In this general period, prior to the start of Project Connect’s “High-Capacity Transit Study” activities in the late summer of 2013, the Central Austin Community Development Corporation (CACDC), led by Scott Morris, posted maps and data for a seven-mile-long Central Corridor urban rail plan following North Lamar and then Guadalupe. As described in our article «Another alternative urban rail plan for Guadalupe-Lamar corridor»,

The CACDC route would extend from the North Lamar Transfer Center, down North Lamar past the Crestview station, through the West Campus area, to 4th St. From there, it includes an eastward spur to the Seaholm development site, and also proposes a short spur line branching from the existing MetroRail Red Line into the Mueller development site.

CACDC proposed 7-mile G-L urban rail route from the North Lamar Transit Center to downtown, then to the Seaholm development site (shown in blue). Existing MetroRail line shown in red. Map: CACDC.(Click to enlarge.)

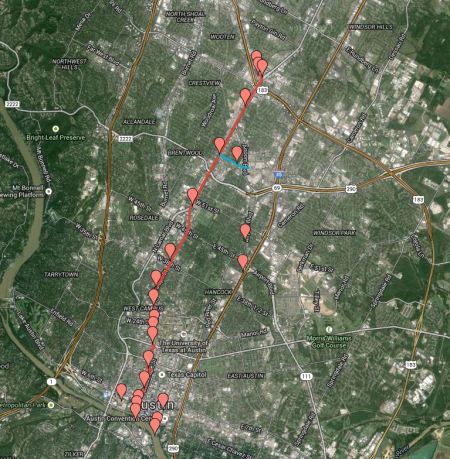

► Skinner proposal — In late November 2013, while debate raged over the Highland-Riverside route recommendation just presented by the Project Connect study team, community activist Adrian Skinner, a member of Austinites for Urban Rail Action (AURA) group, posted on Twitter a map of a proposed urban rail route along the G-L corridor. Skinner’s annotated map (below) indicates nearly two dozen significant points that would be served, from key activity centers to major neighborhoods.

Adrian Skinner map (Nov. 2013) shows important points that would be connected by urban rail in Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. Screenshot: L. Henry.

► ARN Plan B proposal — This plan was devised last October (2014) in response to the contention (mainly articulated by supporters of the Highland-Riverside urban rail ballot measure, but also by some media personnel) that “there’s no Plan B” if the official rail proposal were to be rejected by voters (as, of course, it was on Nov. 4th). As we pointed out in our Oct. 5th article «A “Plan B” proposal for a Guadalupe-Lamar alternative urban rail starter line»,

Apparently, they’re willfully ignoring that there definitely is a “Plan B”. All along, there’s been an alternative urban rail project on the table … and it’s ready to replace the Project Connect/Prop. 1 plan if it fails.

Our proposal aimed to provide an example of a “Plan B” for the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, “a plausible and fairly simple option for an LRT starter line aimed at minimizing design and cost while providing an attractive service with adequate capacity.” As our above-cited article explains, the plan assumes “a 6.8-mile line starting at the North Lamar Transit Center (NLTC, Lamar and U.S. 183) on the north, running south down North Lamar and Guadalupe, then Guadalupe and Lavaca to the CBD, then west on 4th and 3rd Streets to a terminus to serve the Seaholm development and Amtrak station at Lamar. Capital investment cost was roughly estimated at $586 million (2014 dollars), of which it was assumed 50% (less than $300 million) would be locally funded and the other 50% funded via FTA grants.

For this proposed line, our plan also assumed “30,000 to 40,000 as a plausible potential ridership range …, based on previous forecasts for this corridor plus factors such as the interconnection with MetroRail service at Crestview, and extensions both to U.S. 183 and to the Seaholm-Amtrak site.” The route, and several of the most important activity centers served, are shown in the annotated map below.

ARN’s “Plan B” proposed a 6.8-mile LRT line in the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor, from the North Lamar Transit Center to downtown, plus a short branch to the Seaholm-Amtrak site. Map: ARN. (Click to enlarge.)

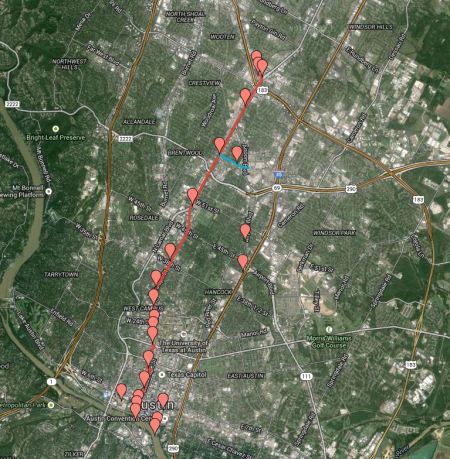

► Parsons proposal — One of the most recent proposals for a Guadalupe-Lamar LRT route was presented in late December by Brad Parsons, a community activist involved with urban and transportation issues. As described in our article «Strong community support for Guadalupe-Lamar light rail continues — but officials seem oblivious»,

Starting at the North Lamar Transit Center at U.S. 183, this route would follow North Lamar Blvd., Guadalupe St., Nueces St., San Antonio St., and finally Guadalupe and Lavaca St. past established central Austin neighborhoods and activity centers, through the West Campus, past the Capitol Complex, and into Austin’s CBD. Brad’s proposal underscores the fact that there’s a variety of ways that LRT can be fitted into this constrained but high-volume traffic corridor.

Parsons’s map, shown below, includes markers indicating key points of interest along the route.

Guadalupe-Lamar LRT route proposed in December by community activist Brad Parsons. Screenshot: ARN. (Click to enlarge.)

Summing up

The experience of more than five decades can be summed up in several major takeaways.

• Clearly, the importance of Austin’s most central travel corridor is underscored by the long history of study and design efforts that has been concentrated on major investments to expand capacity and expedite access, and on planning for a rail line in particular.

• It should be apparent that an enormous volume of examination, evaluation, and analysis has reflected the significant attention — from both the community at large and official agencies — brought to bear on the Guadalupe-Lamar corridor. This has produced an abundance of previous federally approved documentation of the need for LRT in the corridor. In this context, the need for additional study should be minimal — mainly minor updating and evaluation of alignment and design issues.

Recommendations to “go back to Ground Zero” and “start again from scratch” amount merely to a recipe for further delay and dithering. There’s no need for further studies of the re-studies of the re-studies of the studies. It’s high time to finalize a workable, affordable, effective LRT project for this key center-city corridor, and move forward with it.

• Support for LRT among Austinites has endured. This is substantiated by evidence, for example, we’ve shown in our earlier-cited article «Strong community support for Guadalupe-Lamar light rail continues — but officials seem oblivious».

Bolstering this is the support of neighborhood associations, community activists, and residents along in the corridor itself — “the extensive involvement of community activists and residents of neighborhoods along the proposed route” noted earlier has translated into a series of endorsements of G-L LRT from neighborhoods. See: Community endorsements.

• The seemingly interminable saga of indecision, dithering, agonizing, despairing, dallying, official dementia, waste, and delay that has persisted for over half a century needs to come to an end. An achievable, affordable LRT starter line plan is within reach, and the resources to finalize planning for it are at hand. Let’s do it! ■

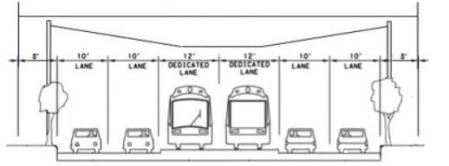

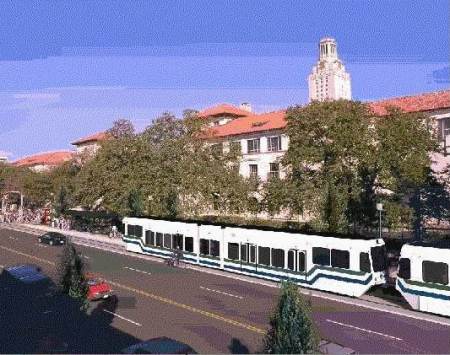

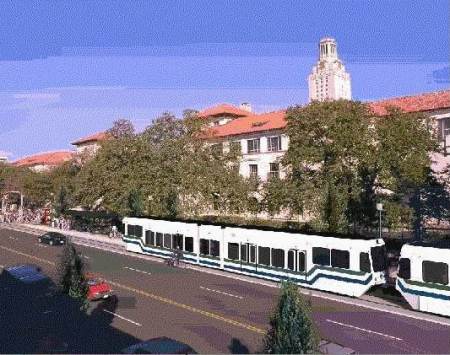

Rendition of LRT on the Drag (2000). Graphic: Capital Metro, via Light Rail Now.