♦

Commentary by Roger Baker

Roger Baker is a longtime Austin transportation, energy, and urban issues researcher and community activist. The following commentary has been adapted and slightly edited from his comments recently posted by E-mail to multiple recipients.

Fast growth over decades, together with a lack of Texas land use planning, leads to intractable peak-hour congestion, as we can readily see in Austin. Service workers try to commute from the cheaper-living suburbs to get to good core city jobs. If good transit were there, many would use it. How could things be otherwise, given a big difference in living costs inside and outside the core city, mediated by crowded highways?

Austin, as the most expensive major city in Texas nowadays, is a good example of the urban gentrification syndrome described in a recent Streetsblog story. As the author Angie Schmitt points out,

Bus ridership is declining in almost every U.S. city. Some reasons are fairly obvious: Lower gas prices combined with higher transit fares and service cuts make transit less appealing.

However, says Schmitt, other factors may also be involved – “rising housing costs, with higher-income residents displacing lower-income residents in neighborhoods that traditionally have had robust transit ridership” – and the article cites an analysis of Portland’s problems published in TransitCenter by two planners, Tom Mills and Madeline Steele, at Tri-Met (Portland’s transit agency). As the StreetsBlog article summarizes,

In surveys, many people told Tri-Met that they ride transit less because of a change of home or work address. This led Mills and Steele to take a closer look at the interplay of ridership changes and the housing market.

According to these analysts’ TransitCenter report,

We found substantial overlap between areas where real market home value increased and transit ridership decreased the most. These areas are concentrated in the same traditionally low-income, inner eastside neighborhoods that have experienced significant economic displacement. Correspondingly, transit ridership grew in areas that saw minimal increases in real market home values. These areas tended to be in the first ring suburbs where many low to moderate-income earners relocated after leaving the inner city.

These economic and demographic dynamics put our most loyal transit riders farther away from our best transit service, and strengthen the market for travel modes that are favored by high-income earning residents who may only use transit to commute.

In her conclusion, Schmitt emphasizes that “For transit agencies, any effective response requires coordination with the cities they serve.”

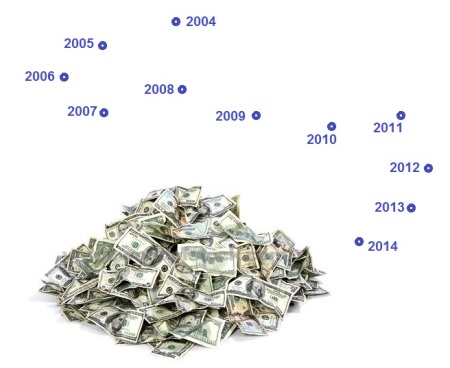

If transit-friendly Portland is losing bus ridership due to gentrification, what chance does Austin have here, where Capital Metro is treated like a reserve cash cookie jar? Austin takes a big part of Cap Metro’s tax money. For example, see page 33 of this link for the agency’s 2015 budget, describing “City of Austin mobility programs” which transferred $26 million out of Cap Metro’s funds to the City of Austin:

Recently TxDOT tried to charge Cap Metro a lot (about $18 million) to make I-35 a supposedly “BRT”-friendly highway, presuming it could be used that way a decade from now, if and when it gets widened. Since nobody can accurately predict population growth, or travel demand, or transit demand, even two years from now, let alone in 2045 as CAMPO is presuming to do, shouldn’t we focus on things that we can measure and see? Like vital transit needs right now. Like current bus problems, including the need to maintain useful service in the fringes, a lifeline as vital as Social Security (and other public assistance) for many old and low-income folks.

If we had a genuinely compassionate and liberal Austin City Council, I think they would say this: You know it is unfair to the voters who approved the full cent for Cap Metro transit in the first place for the City to then divert that money, for decades, and for their own projects. As if bus riders have a permanent obligation to make their personal sacrifice to fund weird city transportation projects. Like the focus on driverless cars which we already know will not improve congestion. Let’s urge the city to give back five or ten million a year of this big unfair mordida to improve fringe city lifeline bus service. It is the right thing to do in these hard times.

The core problem facing Austin transportation is getting people from cheap suburban living to livable-wage jobs using existing highways like I-35 – roads that will never be able to affordably handle this level peak mobility demand. We should learn to regard congestion as self-limiting in nature.

Insofar as this daily peak traffic is partly related to core retail commerce, will these jobs still be there in predicted numbers, after another five years of Amazon killing local retail? How did the planners at Cap Metro get in such trouble with their sales tax projections? Has that budgetary over-optimism been fixed?

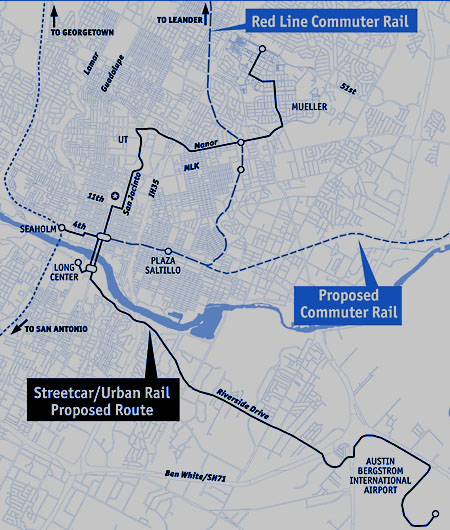

In my opinion, focusing on short-term planning and compassionate meeting of current transit needs in the next few years should get top priority. Included in this category is a $400 million light rail segment down the Lamar-Guadalupe corridor, which is clearly needed today to unclog that corridor. The fact that the City needs a fancy study like Project Connect to arrive at that conclusion is to me a major symptom of our core planning problem. If we could find some way to infuse Austin’s city leadership with more pro-transit leaders (such as those in cities like San Antonio and Nashville), maybe that would help significantly with this problem.

■